When it comes to funding, humanities researchers at the University of South Carolina have historically found grants harder to come by than their peers in the sciences.

That’s where the Office of the Vice President for Research’s Excel Funding Program for Liberal Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences comes in. Aimed at addressing disparities in these fields, the program offers seed funding to faculty members at USC Columbia and the Palmetto College campuses to pursue research projects and increase their competitiveness for external grants.

“Our office is here to serve USC scholars from all disciplines,” said vice president for research Julius Fridriksson. “We know that faculty in the STEM fields, basic and health sciences have access to more funding opportunities than those in the liberal arts, humanities and social sciences. Implementing the Excel program is one way to help level the playing field by offering an internal funding opportunity specifically for these faculty who have fewer options. The goal is for Excel funding to support impactful scholarship in the targeted fields of study, leading to subsequent external funding and major contributions to these important, but often under-resourced subject areas.”

In 2024, the research office is funding 23 Excel projects by faculty from 17 different departments. Meanwhile, members of the 2023 Excel cohort are wrapping up their funding cycle to great success.

Meet some 2023 Excel funding recipients

Jessica Barnes, associate professor of geography

2020 was a flashpoint for the United Kingdom—for the first time, a coroner listed air pollution as a causal factor in a 9-year-old girl’s 2013 death by asthma, and a 2-year-old boy was killed by prolonged exposure to black mold in his home.

Up until that point, Jessica Barnes had conducted much of her fieldwork in the Middle East, writing her first two books on water politics and food security in Egypt. But the headlines of the day, paired with a talk she attended about air pollution in Delhi, drew the U.K. native home to conduct fieldwork on questions of air quality in London.

With funding from the Excel program, Barnes was able to head straight into the field—an essential component of her work as an ethnographer, which requires her to spend time getting to know people in the area she is studying.

“If I said to you, tell me about air quality in your home, you’d probably be like, huh? But if I sit with you for a couple of hours in your living room, maybe I’ll see how you keep your windows closed because you’re worried about traffic from the road outside, or you’ll tell me about how you avoid frying foods because of the smoke. Over time and with close observation, different things tend to come out,” Barnes says. “I learn more about who you are and where you’re coming from.”

This work has enabled Barnes to collect data on how people experience and perceive air pollution outdoors, as they move through the city and in the indoor spaces in which they spend much of their time. London’s infamous smog no longer fills the city as it once did, but with poor air, both outdoors and indoors, nonetheless contributing to a range of poor health outcomes from COPD to Alzheimer’s, Barnes’ upcoming book will tackle questions of visibility — what it feels like to know that that air quality issues may be cutting your life short even if you can’t see it happening.

Though Barnes is in the early stages of data analysis, her multi-scale research is set to highlight a number of issues that will help scholars, students and practitioners rethink their understanding of air.

“My writing will link the work I did inside people’s homes with what’s going on at the city level, and what’s going on at an even larger scale in Europe. It will forefront the day-to-day experience,” she says. “I’m really interested in how this issue is affecting people’s lives.”

Olga Ivashkevich, associate professor of art education

Olga Ivashkevich is passionate about civil rights. Growing up in Belarus, where dissidents are jailed for political views, seeing people unjustly punished hits close to home. That’s why, when she came to the U.S., she was surprised to learn about youth criminalization for first-time offenses like drinking, smoking marijuana or fighting at school.

Now director of the Women’s Well Being Initiative, Ivashkevich became involved with the organization when she arrived on campus, partnering with the Juvenile Arbitration Department of Lexington County to establish an art and media making class.

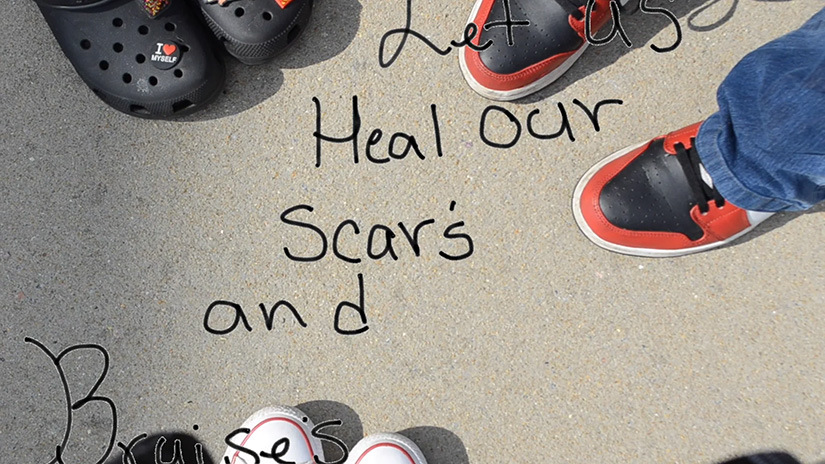

Over the past 16 years, the class has become an established sanction for girls going through a 90-day program to expunge their criminal charges. In Ivashkevich’s classes, girls create multimedia projects exploring challenges they have faced in their lives and the process of healing.

“It’s a great opportunity as someone who believes in the power of the arts to be transformative,” Ivashkevich says. “As an art educator, I want them to own their image and reframe it to the public as capable, creative, powerful poets and artists as opposed to criminal offenders.”

But Ivashkevich is interested in more than rehabilitation – for her Excel project, she researched the construction of South Carolina laws to uncover ways the presence of school resource officers can feed into the school-to-prison pipeline.

“Only half of South Carolina schools have mental health counselors on site. They all have police officers. What picture does it paint?” she asks. “Behaviors do not just pop up out of nowhere—all the girls have issues at home. They need mental health services and help.”

That’s where art education comes into play. Restorative justice-based art programs in schools can redirect problem behaviors before they rise to the level of criminal offenses that lead youth to the juvenile arbitration program.

“We have a very low recidivism rate in this program,” she says. “If you provide youth with a channel to express themselves, build community, talk to each other about the issues they are facing, and address the issues in their lives, they will not reoffend.”

While Ivashkevich continues to research education policy and advocate for change, she hopes that her work with girls in the juvenile arbitration program sparks conversation – thanks to the Excel program, she was able to purchase art and exhibition supplies.

“I was very grateful for the Excel grant because they understand that for some researchers, the involvement in the community or creative projects with public visibility are our research,” Ivashkevich says. “This work is really meaningful to me. It became my life’s work.”

Rebecca Janzen, professor of Spanish and comparative literature

Rebecca Janzen loves reading. It’s what led her to study Spanish and comparative literature in college. It’s also how she approached digging into the topic of religious practices surrounding mining—that is, until grants from the Excel program, the College of Arts and Sciences and the Walker Institute for International Studies allowed her to fly to South America to conduct hands-on research in the field.

Janzen has long been interested in religion, and she first stumbled across the topic of her Excel project while she was a guest professor at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

“There was this huge open pit copper mine. There are several Mormon temples that border it—that’s where they get married and engage in other significant rituals,” she says. “I could not believe they were doing their most important things in front of an open pit mine.

With a background in Central and Latin America, Janzen brought her questions about mining and religion south to Mexico, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia and Cuba, where miners have historically been united by the practice of Roman Catholicism.

Leaning on literary analysis techniques, Janzen’s methods comprise examining archival documents, sacred art and architecture, in their historical context and in conversation with the work of other scholars. After combing through resources located throughout South America as well as in Catholic in the US archives, Janzen has narrowed in on devotion to the Virgin Mary against the backdrop of 19th and 20th century mining sites.

She’s found a wealth of rich case studies while exploring South American archives and mining villages. In Colombia, Janzen toured the continent’s largest underground salt cathedral. In Brazil, she dug into documents detailing lay religious associations of enslaved, emancipated and freed Afro-Brazilian miners devoted to Our Lady in the Rosary and learned more about the association’s burial societies and informal credit unions.

In Bolivia, where Janzen investigated parish records to learn more about practices to look after those deceased due to mining-related illnesses and injuries, she was particularly grateful for the Excel funding that helped enable her yearlong sabbatical for research.

“The Catholic archives I visited are open two days a week, and you need to be able to visit each archive more than once or twice to really understand the collection. It’s really helpful to have more time in a context like that,” says Janzen, who continues to explore her findings. “It’s different going somewhere and doing research than doing it here. Now I can do better reading and research from here.”