If you wanted evidence that a giant comet wiped out the wooly mammoth, you might look for a giant crater.

But so far, you’d be out of luck.

“Some of our critics have said, ‘Where’s the crater?’” says Christopher Moore, an archaeologist at the University of South Carolina. “As of now, we don't have a crater or craters.”

But Moore says that by looking below the surface, you can find strong evidence for the Younger-Dryas impact hypothesis, which states that large comet fragments hit Earth or exploded in the atmosphere shortly after the last ice age, setting off cataclysmic changes in the environment, crater or not.

Digging Deeper

Moore’s research involves digging down to layers of soil that would have been exposed in the Younger Dryas period, around 12,800 years ago when the climate suddenly cooled in the northern hemisphere. He analyzes minerals and artifacts found there in search for “proxies” of a comet strike—findings that are not direct evidence, but which do tell a story.

In Greenland’s ice cores, Moore and others have found elevated levels of chemicals, called combustion aerosols, indicating a large, prehistoric fire raged at the beginning of the Younger Dryas climate event.

In sites as diverse as Syria and South Carolina, he has found platinum, which is rare in Earth’s soil but abundant in comets.

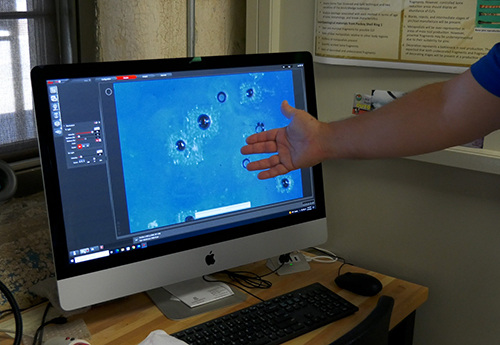

He also has found microscopic, magnetic balls of iron called “microspherules,” which hint that something flung melted iron across the globe.

Moore’s latest discovery involves “shock-fractured quartz” found at three sites in South Carolina, Maryland and New Jersey. These small mineral grains have microscopic cracks where quartz morphed into melted silica. Finding them so far apart adds to the story: Quartz doesn’t undergo metamorphosis and fly 500 miles without a significant impact.

“It’s like putting 75 elephants on a quarter,” Moore says. “It's a tremendous amount of pressure that creates what we're seeing.”

The Science Open journal Airbursts and Cratering Impacts published Moore’s study of shock-fractured quartz this May.

One of Moore’s dig sites for this study was Flamingo Bay, a shallow wetland on the Department of Energy’s Savannah River nuclear site. Other sites included Parsons Island, Maryland, which lies in the Chesapeake Bay, and Newtonville, New Jersey, about 25 miles inland from Atlantic City.

In all three sites, Moore found shock-fractured quartz, platinum, and microspherules more abundantly at depths that were exposed in the Younger Dryas time period compared to surrounding layers of soil.

This was the first time that shock-fractured quartz has been found at the Younger Dryas depth at multiple sites. But it’s also one of the first studies to look for shock-fractured quartz, Moore says, so additional samples may surface in more widespread studies.

A craterless comet?

Moore's findings suggest that a comet struck the earth, scattered minerals far and wide, and caused a massive fire that could have consumed the plants eaten by giant mammals while the smoke from such a fire could have set off a period of global cooling.

“I suspect that it played a big role in leading to the extinction of the megafauna,” Moore says.

But that story raises a couple of questions.

First is the question asked by so many Younger Dryas critics: Where’s the crater?

Moore isn’t writing off the crater yet, but he also says the comet might not have left one. Computer simulations have shown that a comet could explode before hitting the ground and generate a shock wave that could have far-reaching impacts without leaving one identifiable crater, he says.

“They explode in the air before they hit the ground, but if they're low enough, the shockwave and heat can hit the ground and melt sediment, produce microspherules, and shock the quartz,” Moore says, describing the hypothesis.

Then there’s a more existential one: If a large comet hit our planet once, could it happen again?

The answer is yes.

That’s why scientists scan the sky for objects on a collision course with Earth. But the hunt for Armageddon-style comets is not foolproof. Since 2001, military satellites have detected more than 20 large meteors exploding in the atmosphere with enough energy to be mistaken for a nuclear explosion.

These previously undetected meteors blew up in the upper atmosphere—too far from the ground to cause damage, but too close to ignore.

“We’re being hit by these things more than most people think,” Moore says. “It’s just a matter of time before we get something like the Younger Dryas impact.”

Moore isn’t nervous, though. Statistically speaking, most future meteor impacts would have short-lived, local effects rather than global, long-term impacts, he says. But it’s worth it to continue looking.

“We need to think much more about how these impacts may have affected human societies in the past,” he says.