October 18, 2016 | Erin Bluvas, bluvase@sc.edu

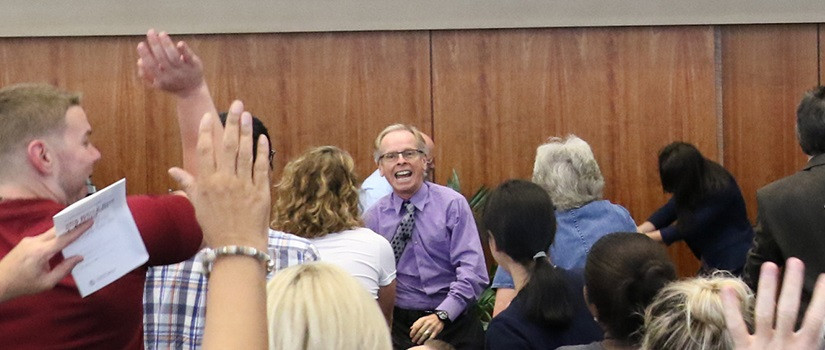

The Gerry Sue and Norman J. Arnold Institute on Aging’s Childhood Obesity 2016 Lecture Series featured a packed house on Thursday, September 29. It also motivated students, researchers, practitioners and others from across disciplines—rallying attendees around the shared mission to eradicate childhood obesity and the domino effects obesity has on individual and population health outcomes across the lifespan.

“I couldn’t be more proud to start this lecture series; it’s one of the first things we’ve been able to do with the recent gift from the Arnold family that established the Gerry Sue and Norman J. Arnold Institute on Aging,” said Arnold School Dean Thomas Chandler in his welcoming remarks. “That gift came with the charge to look at the two ends of the human age spectrum—to look at senior citizens’ mental health and physical wellbeing, and to look at children and adolescents’ health—particularly related to nutrition and physical activity.”

Associate Professor of Exercise Science Michael Beets, who organized the event, recognized graduate students Morgan Clennin (Exercise Science) and Morgan Hughey (Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior) as recipients of the Gerry Sue and Norman J. Arnold Emerging Scholar in Childhood Obesity Graduate Student Research Award. “These two young ladies had outstanding applications in terms of the amount of scholarship they are already doing and their trajectory in their contributions to the childhood obesity area,” he said.

If a field is not doing intervention research with rigorous evaluation, well, you’re not really learning what works...And no guesswork is going to substitute for good evidence.

-James Sallis, Distinguished Professor of Family Medicine and Public Health

Beets also introduced the event’s keynote speaker, James F. Sallis, Distinguished Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Public Health at the University of California San Diego, who has 35 years of experience studying physical activity and its importance to public health. After noting that at least 80 percent of adolescents do not meet national physical activity guidelines, Sallis pointed out that the benefits of physical activity and fitness extend beyond obesity prevention to include enhanced academic achievement and behavioral outcomes as well as many others. To make the greatest impact in increasing the amount and quality of physical activity among children and adolescents moving forward, Sallis suggests adopting a behavioral epidemiology framework—with the explicit goal of intervening and improving, rather than simply studying health benefits.

Sallis explained that researchers need to get precise measures and then apply them during surveillance and establish correlates; they need to develop interventions and evaluate those interventions. “If a field is not doing intervention research with rigorous evaluation, well, you’re not really learning what works,” said Sallis. “And no guesswork is going to substitute for good evidence.”

He emphasized that identifying successful interventions should not be the end point for researchers. “The point of behavioral epidemiology is to improve public health and to create evidence-based solutions that are then implemented,” said Sallis. “If you develop a behavior change intervention and find that it is effective, your job is not done. Because if all that you do is publish it and no one ever uses it, what is your impact on public health? It is zero…The idea is to translate that research into practice and to apply and disseminate effective interventions.”

In terms of research needs and priorities, Sallis suggests focusing on not only the implementation of evidenced-based interventions but also on methods for attracting investment and commitment to these interventions by schools, after school programs, etc. This includes ensuring adequate equipment for physical education courses, for example. “How well could our class learn to read if the whole class was sharing one book?” he asked after showing a photograph of a physical education class with students waiting in line to use one shared basketball.

If you develop a behavior change intervention and find that it is effective, your job is not done. Because if all that you do is publish it and no one ever uses it, what is your impact on public health? It is zero.

-James Sallis, Distinguished Professor of Family Medicine and Public Health

Additional research could focus on how successful interventions are diffused, adopted, and institutionalized, Sallis suggests. Quantifying the public health impact made by these interventions would be beneficial too. Sallis pointed out that a gap in the field is lack of information with regard to economic factors, which can serve as barriers to implementing interventions. Many schools and programs, for example, state that they do not have the funds for interventions (e.g., equipment, instruction, fresh/healthy foods). “We don’t have economic data to refute that, or support that, or provide another perspective, and we don’t have data on what are potential costs or other savings outside more physical activity,” said Sallis. “Decisions about program implementation and sustainability are very often made on an economic basis, so we need to create data to address that.”

Along the same lines, Sallis suggests partnering with communication researchers on the best ways to communicate findings and options to decision makers—with scientific findings translated into plain language through tools such as research briefs, or better yet, infographics. Previous frameworks focus almost solely on efficacy, but Sallis believes researcher responsibilities need to expand. “If you have an intervention that works and you don’t take responsibility for disseminating it, no one else will,” he said.

Other recommendations from Sallis include evaluating existing interventions (e.g., shared use agreements) that are promoted but have not yet been studied or evaluated. Further, getting practitioners, such as program administrators, involved in the research (e.g., research questions) can help with adoption. For example, a superintendent on a research grant team can provide a connection for every stage of the research, from effective data collection to dissemination and implementation.

If you have an intervention that works and you don’t take responsibility for disseminating it, no one else will.

-James Sallis, Distinguished Professor of Family Medicine and Public Health

Evaluation of youth sports, dance, gymnastics and other independent programs is also needed as is the optimization of park designs and other shared spaces within the built environment to ensure usability through safe street crossings, sidewalks, bike facilities, enforced speed limits, etc. Attention to these areas has positive effects on the social environment, such as changing parents’ perceptions about safety and appeal of engaging in physical activity within the community.

In addition, Sallis sees opportunities in partnerships and funding within the field of epigenetics and how and why physical activity affects genes. “This is a way to move our field forward, to improve our measures of behavior and environment, to get involved in bigger studies,” he said.

Sallis closed with invitations to join the discussions and future of youth physical activity research at the Active Living Research Conference in Clearwater, Florida in 2017 as well as the International Physical Activity and Health Conference in Thailand in November.