About a week into Dr. Martha McCoy’s career as a veterinarian, her first patient arrived at Four Paws Clinic in downtown Columbia: a tiny kitten that had been struck by a car.

“Save this kitten,” said the future owner, who had found the animal on Assembly Street.

The assignment was clear — save the kitten — but for the newly minted veterinarian, this first emergency gave her pause. No amount of training could have prepared her for the shock of a surprise patient and a panicked owner.

“I’m of course like, ‘I don’t know what to do,’” McCoy (2017, biology) recalls. “The doctor who was mentoring me was like, ‘Okay. You can do this. Get an exam, take some vitals. What’s your plan?’”

With a few deep breaths and a moment to collect herself, the years of study, shadowing, research and training would come back to her. And here’s the thing about Martha McCoy: The former University of South Carolina cross country team captain knows how to stay the course, and once she begins, nothing will stop her.

A new route

McCoy’s journey to veterinary medicine began the summer after her first year at USC. The biology major shadowed at a veterinary clinic in her hometown of Johnson City, Tennessee, and returned to school with two takeaways: a defined career goal and an eyeball in a glass jar.

“I spent the whole summer just hanging out in a vet clinic, and that kind of sold me because I had no clue — I think most lay people have no understanding of what we do,” says McCoy. “You kind of have the front image, of course, if you ever had a traumatic experience or had to deal with something, of course you have that in your memory. But what we do day to day is very different than what I think people understand that we do.”

Fascinated by the dual approach to treatment — providing assistance and care to both the animal and its human — McCoy continued her studies with renewed excitement and vigor, keen to access as many opportunities as USC and the South Carolina Honors College had to offer.

She credits her Honors classes and professors for working with her when she was traveling for cross country, allowing her to stay engaged with coursework while competing. Throughout her USC cross country career, McCoy and her teammates had one of the highest combined grade point averages in the United States. When she wasn’t running or studying, McCoy was in the research lab conducting genetic research with butterflies.

“I feel like there was always three pieces of me. There was the student, and I always felt like I was a student first, always been that way,” McCoy reflects. “And I think that's why I've done well. So student, and then the athlete side, and then what was left would be free time and whatnot. But those two took the majority of my time, but if anything I think it helped me. I'm very much a person who likes to have structure. Just tell me where I’ve got to be, what I’ve got to do.”

Compassion and connection

In veterinary school at Auburn University, McCoy would learn that she’d discovered her passion for veterinary medicine later in life than many of her peers; most had wanted to be a vet since childhood. But she wasn’t behind in her studies: Her coursework at USC had provided a solid foundation for her graduate studies.

Veterinary school, according to McCoy, is “very science heavy. There’s of course anatomy and physiology, but you’ve got cell biology, genetics, and I did research in genetics and stuff when I was [at USC]. So that was all in my wheelhouse. I felt like I handled the jump to grad school a lot better [than my peers] because of what I had.”

McCoy’s leadership experiences also benefited her in vet school, where she was president of the One Health Club. Now a practicing veterinarian, McCoy is still interested in the intersection between public health and veterinary medicine. Veterinarians, she explains, have a unique position in the medical community, serving a large population that coexists with humans and can impact human health in a number of ways.

“I think where public health comes in mind for me is that there are times when, having discussions with owners, we’ll be like, ‘Look, here’s what I would love to do, but here’s what I know you can do, and I want to respect your relationship with your dog,’” says McCoy. “There are times I shift what our plan will be because I know what will hurt their bond a bit more.”

This passion for addressing and investigating the human-animal bond is a driving force behind McCoy’s daily work. Since her patients can’t communicate through speech, she takes extensive histories, relying on owners’ connections with their pets. It takes time, trust and care to build these relationships; every question, every conversation leading to an accurate diagnosis is crucial.

When she’s not talking, she’s observing. A tilt of the head, a soft whine, a small bump hidden beneath thick fur — all could be important clues. But sometimes the animals can hide their symptoms. A dog that McCoy treated during the COVID-19 pandemic presented for limping, then showed no signs of pain during the exam — until he started limping again when his leash was handed over to his owner in the parking lot.

“And that’s a big movement among veterinarians, to try to make our visits less stress-inducing,” says McCoy. The less fear and adrenaline the animals experience, the more effectively they can be diagnosed.

Another major movement among vets, according to McCoy, is prioritizing their own mental health. Veterinary care is in high demand, and cases are often emotionally taxing.

“‘Compassion fatigue’ is the term they use,” she explains. Fortunately, the increase in emergency veterinary clinics has relieved some of the burden from general practitioners, and McCoy hopes that more corporately owned clinics will offer mental health resources and counseling for veterinarians.

She’s grateful to work in one such clinic. But her favorite way to relax after a long day of practice is, of course, running.

The long run

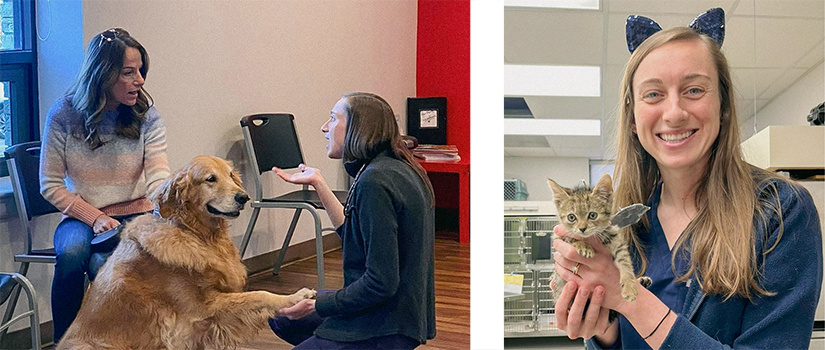

In the Four Paws clinic, McCoy’s journey has come full circle. A current SCHC student intern works in the clinic, and now it’s McCoy’s turn to be observed. “That’s the best thing you can do,” says McCoy. “Even if you’re pre-med, or pre-PA, PT, just go shadow somebody, understand what it is they do.”

These days, appointments keep McCoy busy, and she hasn’t ruled out a transition into public health later in her career. But her patients are her top priority — including a certain injured kitten that is now a full-grown cat. Thanks to McCoy’s treatments three years ago, the cat now enjoys a happy and healthy life.

“Thankfully, I work in a multi-doctor practice, and I had plenty of people around to ask questions,” says McCoy, thinking back to her first patient. “But now the tables are turned because all of the sudden I’m the person people ask questions to, and I find that hilarious and a little scary some days. But I work a lot, have seen a lot of stuff even in three years...you learn a lot just by doing it.”