100 years of suffrage

SC women in the fight for voting rights, equality

Posted on: August 6, 2020; Updated on: August 6, 2020

By Page Ivey, pivey@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-3085

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories commemorating 100 years of women’s suffrage by examining the history of the women's movement in South Carolina and the role UofSC plays in documenting and preserving that history.

The progress of women in South Carolina, much like the history of women in the U.S., has come in fits and starts. Each new step forward has been challenged by bigotry and misogyny and, in many cases, those two oppressors have ultimately led to the progress. As is often the case in a struggle for equality, education mixed with individual courage was the recipe for advancement.

Adding to the already difficult battle in South Carolina was the separation of the fates of Black and white — with parallel efforts made by organizations to get the vote for women and the fight continuing for Black women in the state until the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Even the recognized start date for the women’s suffrage movement in South Carolina is complicated by race.

Many historians point to newspaper owner Virginia Durant Young, who pushed for women’s suffrage leading up to and following the South Carolina Constitutional Convention in 1895, as the beginning of the women’s movement in the state.

“That’s usually where people think South Carolina’s suffrage movement starts is with her,” says Valinda Littlefield, professor of history and African American Studies at the University of South Carolina. “But that’s not the real place the suffrage movement starts and that needs to be corrected.”

Littlefield says the suffrage movement in South Carolina actually began with the Rollin sisters, who were part of Charleston’s antebellum “colored aristocracy” and who started their push for suffrage nearly 30 years before Young during the Reconstruction Era when state government was run under the protection of the U.S. military and the federal government.

UofSC oral historian Andrea L'Hommedieu has worked with historians to transcribe hundreds of recordings made of women who participated in the National Women's Conference in 1977.

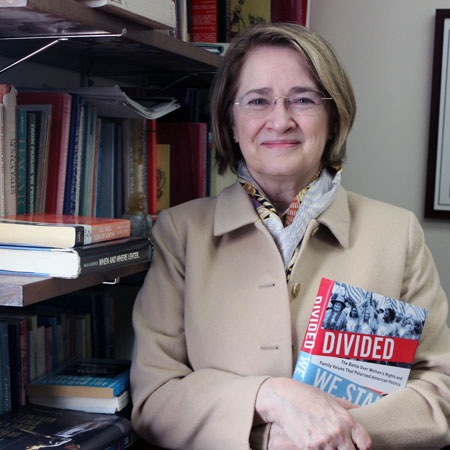

Littlefield and fellow UofSC history professor Marjorie Spruill are a big part of uncovering and telling the stories of women in South Carolina. The two, along with historian Joan Marie Johnson, co-edited a three-volume collection of historical essays South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times that tells the stories of women living in the state from the 16th through the 21st centuries. Much of the research was facilitated by collections of many of the spotlighted women that are a part of University Libraries’ Special Collections, the South Caroliniana Library and the Department of Oral History. Spruill, who chronicled the battle over the Equal Rights Amendment in Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women's Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics, has been working with UofSC oral historian Andrea L’Hommedieu to digitize and transcribe 700 interviews that were conducted in 1977 during the National Women’s Conference in Houston and during a preceding state conference in South Carolina. About half of the recordings with transcripts are available online. The 1977 interviews were part of an oral history research project for which UofSC alumna Constance Ashton Myers was principal investigator.

“Both the suffragists collection and the IWY (International Women's Year) collection were spearheaded by the late South Carolina history professor Constance Ashton Myers,” says L’Hommedieu. “She was both a feminist and an early advocate of oral history methodology.

“Women's voices have been underrepresented in history, so preserving these stories not only validates women's experiences and amplifies the fight for equality, but as importantly the stories now exist as primary research material for those wanting to write about women's achievements and struggles for equality.”

![Conferring over ratification [of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution] at [National Woman's Party] headquarters, Jackson Pl[ace] [Washington, D.C.] 1919. L-R Mrs. Lawrence Lewis, Mrs. Abby Scott Baker, Anita Pollitzer, Alice Paul, Florence Boeckel, Mabel Vernon (standing, right)](/uofsc/images/feature_story_images/2020/large_story_image_08_suffrage_anita_pollitzer.jpg)

Where the struggle began

Nationally, the women’s rights movement was born in 1848, with the Declaration of Sentiments signed by 300 men and women meeting in Seneca Falls, New York, that called for the end of discrimination against women. The activism started with that document culminated in the adoption and ratification of the 19th amendment in August 1920, giving women the right to vote in the United States.

But even before that seminal moment, some South Carolina women who had taken on nontraditional roles, at the very least had pointed out the inequities in the treatment of men and women by the law and society.

The Grimke sisters — Sarah and Angelina — were native-born South Carolinians who renounced their family’s practice of keeping slaves and moved to Philadelphia to take up the abolitionist cause. In 1838, Angelina Grimke became the first woman to address a meeting of a state legislature when she spoke to the Massachusetts Legislature on abolishing slavery, which she said was a sin that endangered the soul of the slaveholder. Her ensuing fame led the General Association of Congregational Churches of Massachusetts to denounce the actions of women abolitionists “who so far forget themselves as to itinerate in the character of public lecturers and teachers.” Some in the abolitionist movement even thought that having women take such strident roles, and in the process making the case for the right of women to do so, could damage their anti-slavery cause. The pushback simply led the sisters to advocate for women’s rights as well as for ending slavery.

The comparison of the position of a married woman to the position of a slave also found its way into the writing of Mary Boykin Chesnut, a well-born and well-married Southern author whose Civil War diaries, include the line: “the Bible authorizes marriage & slavery — poor women! Poor slaves!”

UofSC historian Marjorie Spruill chronicled the battle over the Equal Rights Amendment in Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women's Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics. She has been working with UofSC oral historian Andrea L’Hommedieu to digitize and transcribe 700 interviews from the National Women's Conference in 1977.

Chesnut’s diary first appeared in the early 1900s, under the title, A Diary from Dixie, and “revealed a strong support for the end of slavery among Southern women, whom Chesnut felt were also enduring a kind of enslavement by the traditional male-dominated patrician society of the South,” Spruill says. “The author reveals a strong revulsion for the moral lapses that such a system tolerated, giving the example of her father-in-law's liaison with one of his slave women.”

Chesnut referred to slaveholding plantations as places where men’s wives and “concubines” lived under the same roof with mixed-raced children playing beside their white siblings. “Every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in every body’s household, but those in her own, she seems to think drop from the clouds.”

Following the war, Chesnut — whose family papers are in University Libraries’ Special Collections — reworked the material from her diaries into a more nuanced narrative of the Old South and the war. A first edition of the book A Diary from Dixie — heavily edited — was published in 1905, nearly 20 years after Chesnut died, but 75 years later, a second version that included much more of her original diary and material that she had rewritten herself was published as Mary Chesnut’s Civil War in 1982.

Battle for suffrage, era of ‘firsts’

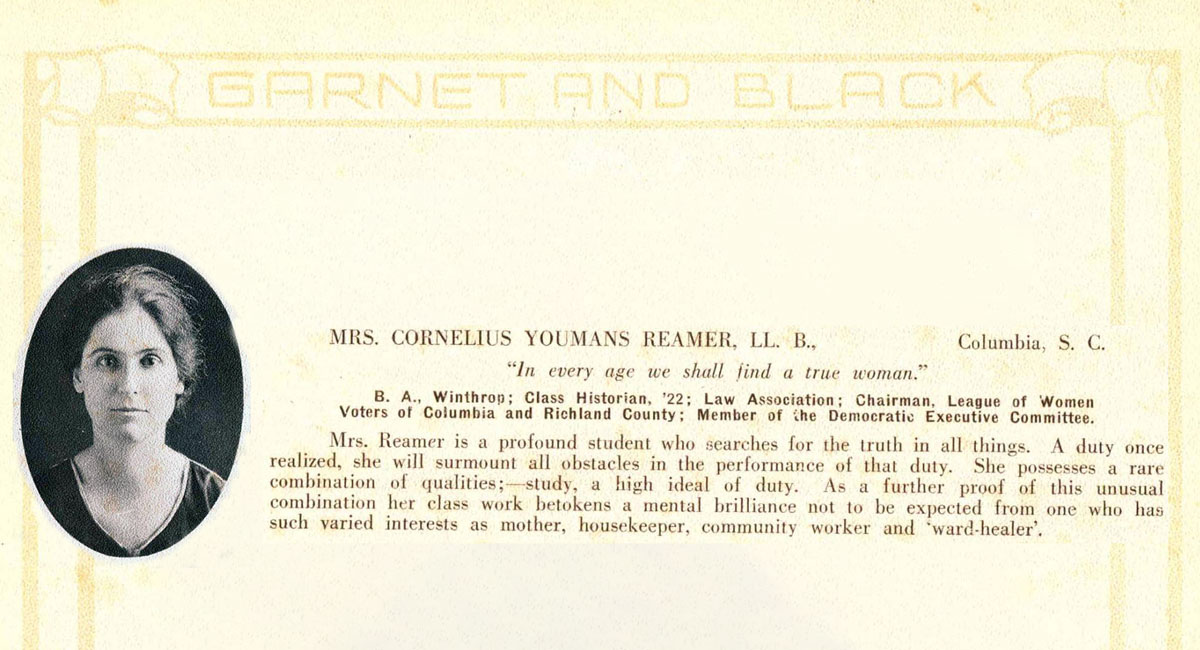

As early efforts to get women’s suffrage into the South Carolina Constitution failed, a new push came in the early 20th century when well-connected and well-educated women from some of the state’s best known political families took up the fight. While their efforts were not successful — the state Legislature did not formally ratify the 19th amendment until 1969 — women still made incursions into new fields, such as law and medicine, with UofSC graduating its first female law student in 1918 and, four years later, Ida Salley Reamer, who had spent years traveling the state campaigning for suffrage, graduated first in her UofSC law class of 1922.

Women also won elected office and focused on issues around education, child welfare and families. Among those was Mary Gordon Ellis, whose papers are at the South Caroliniana Library. Ellis also fought for better schools for African American children, but she was something of an outlier with women’s experiences and advances differing significantly based on race.

“The other thing about that particular beginning of the suffrage movement in South Carolina — the Rollin sisters — it included Black and white,” Littlefield says. “But the shifts happen later and you get the women’s movement moving on parallel tracks, but never together.”

UofSC historian Valinda Littlefield has worked to tell the stories of women who fought for suffrage and equal rights. She is a co-editor of the three-volume compilation South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times.

During the World War II, for example, when white women signed up by the thousands as nurses and members of auxiliary branches of the armed forces, Black women were relegated to small, segregated units when they were allowed to join at all.

But even under those constraints, women of color broke new ground, including Cassandra Maxwell, who became the first African American woman admitted to the South Carolina Bar (1940), though it would be another 25 years before women could serve on juries in the state. Maxwell worked on the faculty at the law school at South Carolina State University, the historically black college in Orangeburg, before moving to Atlanta, where she assisted Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP on cases that ultimately overturned the legality of segregated public facilities in the South.

And in 1963, Henri Monteith Treadwell became the first African American woman to enroll at UofSC, and two years later became the first Black student since Reconstruction to graduate from the university.

The second wave

The second wave of feminism that began in the 1960s, hit a high point in 1972 with the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment in the U.S. Senate (1972). It was sent to the states for ratification and some states approved it immediately.

“Even in this state, the House actually approved it by a unanimous voice vote,” Spruill says. “But then Sen. Marion Gressette, who was the most powerful senator, blocked it.”

Nationally, the emergence of Phyllis Schlafly as a faith-based opponent to the ERA and women’s rights in general stopped the amendment virtually in its tracks. Spruill points out how the fight over the ERA set the tone for today’s politics.

“Studying that period helps us understand where we are today,” says Spruill, whose expertise on the ERA and the women’s movement was called upon as the recent television series Mrs. America piqued public interest in the time. “That fight really set the tone — the rather acerbic, hostile tone — of modern American politics: Don’t just disagree, but demonize your opponent.”

The ERA has returned to the political arena as Virginia recently became the 38th state to ratify it, not counting the handful of states that have over the years withdrawn their earlier ratification. It is unclear what impact the new action or the withdrawals have, given that the deadline for ratification was nearly 40 years ago.

In the 21st century, women have seemed to be reaping the rewards of the feminist movements with 2020 seeing the most women ever holding seats in Congress — nearly one-quarter — and women justices make up one-third of the U.S. Supreme Court. While women account for less than 10 percent of the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, South Carolina got its first female governor (Nikki Haley in 2010), and Hillary Rodham Clinton put a crack in the highest glass ceiling in 2016 as the first woman to receive a major-party nomination to be president of the United States.

Banner Image: Suffragettes with Banners event in Washington D.C. 1918. Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, [LC-DIG-hec-11369]