100 years of suffrage: After the vote, comes an era of 'firsts'

After 1920, SC women turn their attention to politics, breaking new ground in many fields

Posted on: August 20, 2020; Updated on: August 20, 2020

By Page Ivey, pivey@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-3085

South Carolina’s few but dedicated suffragists were no doubt disappointed that the state was not among the first 36 to ratify the 19th amendment — and indeed South Carolina would not do so for nearly 50 years. But they almost immediately set about the business of turning their suffrage organizations into education and advocacy groups, taking on many more issues of equal rights for women and for African Americans. And in the process, these bold women kicked off the era of “firsts.”

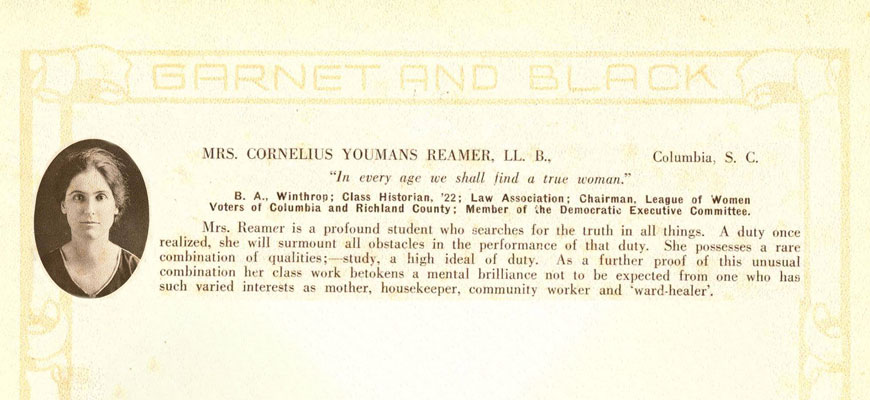

Ida Salley Reamer spent six years traveling the state petitioning for women’s suffrage. While her campaign in South Carolina failed, she became the inaugural president of the League of Women Voters of Columbia after national ratification. In this role, she led lobbying efforts to raise the age of consent and end child labor; she did all this while also graduating first in UofSC's law class of 1922.

The UofSC yearbook Garnet and Black noted her graduation: “Mrs. Cornelius Youmas Reamer, LL. B., Columbia, SC, “In every age we shall find a true woman.” B.A. Winthrop; Class Historian ’22; Law Association; Chairman, League of Women Voters of Columbia and Richland County; Member of the Democratic Executive Committee.

“Mrs. Reamer is a profound student who searches for the truth in all things. A duty once realized, she will surmount all obstacles in the performance of that duty. She possesses a rare combination of qualities: study, a high ideal of duty. As a further proof of this unusual combination her class work betokens a mental brilliance not to be expected from one who has such varied interests as mother, housekeeper, community worker and ‘ward-healer.’ ”

That same year, Kate Vixon Wofford became the first woman to hold elected office in South Carolina when she became superintendent of education in Laurens County in 1922.

The next year, the first version of an Equal Rights Amendment was introduced nationally with the words: "Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction."

In 1928, Mary Gorden Ellis, who had previously been elected superintendent of education in Jasper County, became the first woman elected to the South Carolina Senate. In addition to her historic first, Ellis, who was white, was an early champion of educational opportunities for African Americans. As the superintendent in Jasper County, where 60 percent of school-age children were Black, she worked to get funding from the northern philanthropist Julius Rosenwald who had established a foundation to improve educational opportunities for African Americans.

Ellis encouraged women to seek elective office. In a profile for the three-volume South Carolina Women: Their Lives and Times, University of South Carolina Aiken Distinguished Professor Emeritus Carol Sears Botsch quotes Ellis’ perspective: “As for going into politics, why not? Women meet unpleasant situations in other facets of life, why not in politics?”

She also seemed to understand very well the nature of politics in the Palmetto State, telling the Business and Professional Women’s Club in Columbia: “Selfishness and the fear of politicians that they will not be returned to office if they sponsor certain measures are responsible for the backwardness of South Carolina.”

Ellis, whose papers are at South Caroliniana Library, served just one term in office, becoming gravely ill during her failed re-election bid. She died in 1934 at the age of 44, one day after casting an absentee ballot in the 1934 election. More than 60 years later, she was honored with her portrait being hung in the South Carolina Senate chambers.

Four years after Ellis’ death, Elizabeth Hawley Gasque of Florence became the first of five South Carolina women to be elected to Congress, when she won a special election to finish the last three months of the term of her husband, U.S. Rep. Allard Henry Gasque, who died in office. She did not seek re-election. Her personal papers are included in her husband’s papers at the South Caroliniana Library.

Education

Ellis and other political groundbreakers were followed by many women who found a cause in improving education for all South Carolina children, but especially for Black children.

Laurens County native Wil Lou Gray focused on eradicating illiteracy in South Carolina, pioneering the concept of adult education programs. After graduating from Columbia College in 1903, Gray taught school in rural Greenwood County where the upper-class daughter of a lawyer got her first experience of the poverty and illiteracy rampant in turn-of-the-century South Carolina. She did graduate work at Vanderbilt and Columbia University in New York, earning a master’s degree in political science in 1911. She created an adult night school in 1915 while she was serving as a schools supervisor in Laurens County and worked with the South Carolina Illiteracy Commission right after World War I. From 1921 to 1946 she was the South Carolina Supervisor of Adult Education and experimented with different methods of teaching adults, including the creation of opportunity schools with a curriculum that included home economics, etiquette, practical skills application and citizenship. She also undertook a successful scientific experiment in 1931 to prove that Blacks were just as capable of learning as whites. The Wil Lou Gray Opportunity School is still operating today, providing at-risk 16- to 19-year-olds a chance to complete their high school education.

“I feel that it’s the women that have been interested in the development of the people of the state, which after all is really the most valuable asset we have,” Gray says in an oral history interview with the late South Carolina history professor Constance Ashton Myers that is available on Oral History Department website.

Gray, whose papers are at South Caroliniana Library, retired from full-time work in 1957, but continued to serve the state as a volunteer, including organizing the South Carolina Federation on Aging, which was a voice for older residents. She died in 1984 at 100 years old. Like Ellis, Gray is honored with a portrait in the South Carolina State House.

As for going into politics, why not? Women meet unpleasant situations in other facets of life, why not in politics?

Mary Gordon Ellis, first woman elected to the SC Senate

South Carolina native Mary McLeod Bethune served as special adviser on minority affairs under President Franklin Roosevelt, organizing national conferences on issues facing African Americans. Born to former slaves in 1875, Bethune saw education as a way out of poverty for African Americans. She taught in Georgia and South Carolina before moving to Florida and opening her own school, which would become Bethune-Cookman University. She served as president of the State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, working to end school segregation and improve health care for Black children, and in 1935, she founded the National Council for Negro Women.

Shortly before her death in 1955, Bethune wrote her “Last Will and Testament” detailing her “principles and policies in which I believe firmly, for they represent the meaning of my life's work. They are the products of much sweat and sorrow.”

Among these principles are love, hope and faith in one another, respect for the uses of power, racial dignity and “a thirst for education. Knowledge is the prime need of the hour.”

Like Ellis and Gray, Bethune’s portrait also hangs in the South Carolina State House.

Law

Sarah Leverette, became just the 35th women admitted to the S.C. Bar after she graduated as the only female in the UofSC law school’s class of 1942. She returned to her alma mater to work in the law library and teach, the first woman to gain faculty status there. Born in Iva, South Carolina, in 1919, Leverette also earned a bachelor’s degree from UofSC. She was in the Civil Air Patrol and was in leadership in the League of Women Voters.

In her 25 years as law librarian, Leverette assisted students with research and taught legal writing and workers’ compensation law. She also served on the board of the South Carolina State Employees Association and worked on committees tasked with revising South Carolina’s State Constitution of 1895. After “retiring” from UofSC in 1972, she was appointed to the Workers’ Compensation Commission, where she served for six years before becoming a consultant to the board until 1985.

Leverette followed that up with a successful career in real estate and continued her work with women’s legal and academic organizations. “I do not believe in retirement as a way of life,” she said in 2002. “I soon discovered that retirement was the most boring state of existence imaginable.”

Leverette, whose papers are in University Libraries’ South Carolina Political Collections, died in 2018.

Sports and medicine

All the “firsts” and other successful endeavors for South Carolina women were not only in the political or legal world.

Lucile Ellerbe Godbold from Marion County became one of the U.S.’s first female athletic champions, competing in the shot put, the discus, and the forerunner of the triple jump for Winthrop College. She made the U.S. national team that competed in the first international track meet for women as part of the women’s 1922 World Meet in Paris. Godbold competed in six events, setting a world record and winning gold in the 8-pound shot put with a distance of 20.22 meters. She won gold in the triple job (known then as the hop-step-jump), came in second in the basketball throw and third in javelin. Upon her return to South Carolina, Godbold became director of physical education at Columbia College where she worked for 58 years. In 1961, she became the first woman elected to the South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame.

Thirty years later, South Carolina native Althea Gibson became the first African American tennis player to compete at the U.S. National Championships (1950) and the first black player to compete at Wimbledon (1951). She also would go on to become the first Black player to be ranked No. 1 in the world (1952); the first African American to win a Grand Slam title, at the 1956 French Championships, and the winner of both the U.S. national championship and Wimbledon in 1957 and 1958.

In the world of health and medicine, rural physician Hilla Sheriff helped combat pellagra, a disease caused by a lack of dietary niacin, among her poor patients in Spartanburg County and helped train a generation of white and Black midwives who often provided the only medical care poor pregnant Black women would receive in the state.

Sheriff, whose papers are held by the South Caroliniana Library, earned her medical degree in 1926 and opened a pediatric practice in Spartanburg in 1931. She also took on the additional role of medical director for the American Women’s Hospital Unit for Spartanburg County and later Greenville County.

Sheriff also promoted good nutrition and maternal and child health care throughout her career, as well as family planning services. In the 1940s, she served as director of the Division of Maternal and Child Health of the State Board of Health — the state’s first female health officer — and when she retired in 1974 was deputy commissioner for the state Department of Health and Environmental Control as well as chief of the Bureau of Community Health Services.

Civil rights era

With the coming of the Civil Rights movement in 1950s and ’60s, South Carolina women, including Modjeska Monteith Simkins, Septima Poinsette Clark, Bernice Robinson, and Marian Wright Edelman worked in the fields of law and education to break down the barriers of segregation in schools and other public facilities.

Simkins’ experiences as a teacher helped in a lawsuit brought against Clarendon County that ultimately was rolled into the case Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Supreme Court in 1954 struck down separate schools for Blacks and whites.

Clark and Robinson were instrumental in establishing Citizenship Schools across the South that taught Black residents how to read so they could vote. The schools are credited with helping 2 million African Americans exercise their right to vote.

Bennettsville native Edelman became the first African American woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar in 1964. She went on to create the Children’s Defense Fund, a privately funded organization that conducts research and advocates for children. Edelman’s 1992 book The Measure of Our Success: A Letter to My Children and Yours, includes two dozen lessons on life that address issues common to everyone regardless of age, race, gender or religion. The book was selected for the university’s First-Year Reading Experience in 2016.

Edelman, who has been a hero to many in the modern battle for racial and gender equality, talked then about her heroes.

“Every day, I wear a pair of medallions around my neck with portraits of two of my role models: Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. They represent countless thousands of anonymous slave women whose bodies and minds were abused and whose voices were muted by slavery, Jim Crow, segregation and confining gender roles throughout our nation’s history. When I think I’m having a bad day, I think about their days and challenges, and I get up and keep going.”

The efforts of these women in the civil rights era led to one of the 1960s biggest groundbreaking moments for the University of South Carolina, when Simkins’ niece Henrie Monteith Treadwell in 1963 became the first Black woman to enroll in the university and two years later was the first African American graduate since Reconstruction. After earning a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from USC, Treadwell continued her education in Atlanta, earning a master’s and doctorate in biochemistry. Today, Treadwell is the director of Community Voices at Morehouse School of Medicine where she studies health care for underserved populations and researches the health concerns of teenage African American males, including prison health, health policy and health services.

Banner image: Ida Salley Reamer graduated first in her UofSC law school class of 1922 after spending a half-dozen years traveling the state in support of women's suffrage. She also served as the first chairman of Columbia's League of Women Voters. Images taken from 1922 edition of Garnet & Black yearbook, South Caroliniana Library.