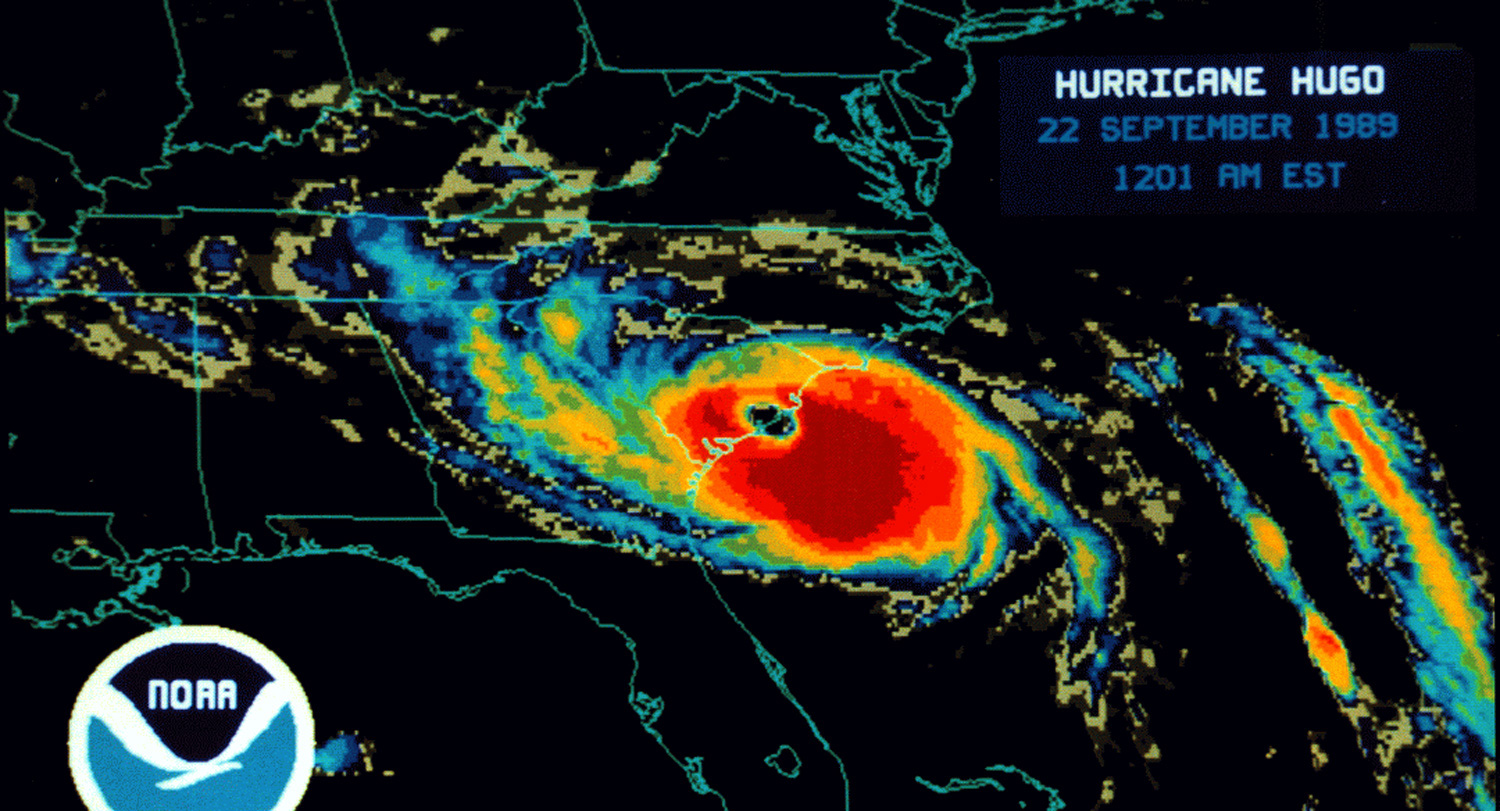

Every summer, the South Carolina coast and the southeastern United States faces the threat of hurricanes that range in size from sustained winds of 74 mph to the Labor Day hurricane of 1935 with its estimated top sustained wind speeds of 185 mph, to the state’s most catastrophic hurricane, Hugo in 1989 that resulted in $10 billion in damages.

Accordingly, the damage wrought by these storms ranges from downed trees and power lines to devastating flooding and loss of property and life.

Helping minimize that damage is the job of several graduates of the University of South Carolina’s geography master’s program.

Geography?

“Yes,” says Susan Cutter, Carolina Distinguished Professor of geography and director of the Hazards Vulnerability & Resilience Institute.

“We provide training in hazards and disasters, including the preparedness response, recovery and mitigation,” she says. “Students obviously have certain interests themselves in terms of perhaps their ‘favorite hazard’ or focus area such as preparedness, mitigation or recovery. But they get all that foundational training here at the university and specifically within the geography department.”

As far as the “favorite” hazard of hurricanes, three graduates in particular are on the front line in South Carolina and nationally, helping prepare us for the increasingly virulent storms that develop between June 1 and Nov. 30 in the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Christina Finch discovered her love of geography and disaster prep while she was a student at Salisbury University in Maryland, where she grew up.

While trying out several majors, she took a campus job in the geography department, where she signed up for a class on hazards and disasters taught by Mike Scott, an alum of USC’s geography program and Cutter’s lab.

“I was hooked from Day One,” Finch says. “I can use math and science, my interest in geographic information systems and making maps. I even get to use a little bit of my art interest in developing communication products and understanding how people learn and receive information.”

She got into Cutter’s program at USC — her first choice — and came to South Carolina in 2002.

A couple of years later, four hurricanes hit Florida and the Federal Emergency Management Agency needed workers to help with GIS and analytical support.

“Hazards and disasters is such an interesting intersection of how we design our communities and our human social systems and how that interacts with physical hazards like a hurricane threat, whether it be wind or rain or storm surge,” she says.

Finch’s 30-day stint with FEMA turned into six months, and she continued to deploy to field offices to support hurricane response and mitigation.

“It really cemented for me that experience of getting to apply my knowledge and skills to helping people before, during and after disasters. And so that's basically what I've been doing ever since — almost 20 years now.”

While hurricane season runs from June through November, Finch’s current role, as the National Hurricane Program manager, stresses the importance of “blue-sky days,” helping communities prepare their evacuation plans and other responses to storms.

FEMA provides data to help those emergency managers understand how storm surge — one of the deadliest components of a hurricane — will affect different communities based on geography, storm size, strength and forward speed. The agency also helps communities create evacuation zones and plans to help them figure out how long it would take to get everyone out of each zone, all key factors to preventing loss of life in a storm.

“That's something we would typically do on a blue-sky day,” she says. “That way, when a storm is threatening, they already have that information from their planning scenarios to support their really difficult decisions on whether to issue evacuation orders and which zones to evacuate.”

FEMA’s information and tools are free to emergency managers at all levels and the agency conducts training throughout the offseason to teach those managers how to use the tools and what to expect during a hurricane.

“Sometimes it feels almost busier than our operational season during the Atlantic hurricane season because we try to fit so much engagement and training and readiness efforts in such a short time of year,” she says. It is the critical to use this time to before a storm to ensure emergency managers have the best available information and are ready with actionable plans.

Melissa Potter is also a Salisbury University alum who took Scott’s geography course on natural hazards. The year was 2005.

“The whole class became kind of like a Hurricane Katrina course,” says Potter, chief of preparedness at South Carolina Emergency Management Division. “The whole nation was watching and what better incident to investigate further and research to see the response and the recovery in real time.”

She talked with Scott about her interest in the field of hurricane preparedness and he recommended USC and Cutter’s lab, where he had worked as a grad student.

Potter was drawn to the work the lab was doing, particularly the Social Vulnerability Index, which looks at a variety of factors, including economic, demographic and housing characteristics that influence a community’s ability to prepare for and respond to environmental hazards.

Hurricane Katrina gave the students in Cutter’s lab an opportunity to test how well the index predicted damage and recovery in different communities.

“Carloads of USC students from the lab got in cars and we had a grid mapped out on the coast. It was a square-mile grid,” Potter says. “I was on the Mississippi side and the idea was to go to each one of those grid points and see was there damage there, what was the level of damage and take a picture of it.

“They went back every six months for like five years. I got to go on at least two of those trips and to see what that recovery process looked like. If there was a destroyed home, did they rebuild? If they had damage, could they do the repairs? Did they come back? Do they live on the property? Were they getting FEMA assistance? We looked at post office records to figure out if people were actually living there, trying to piece it together.

“Some people within a year or 18 months, they might have a brand new house, and some people, five years later, were still living in a camper on their property.”

Being able to tease how the index’s reliability meant it could be a valuable tool in preparing high-risk areas for a coming storm, which is precisely what Potter does at Emergency Management.

That kind of research and knowledge also helps Potter as she goes out into communities to find ways to prevent damage by investing in infrastructure repairs and upgrades, which can sometimes be a hard sell.

“We try to convince people that it's worth the investment and that for every dollar you put into mitigation, you'll get $6 in return of avoided losses,” she says. “But it's so hard for governments and for the average individual to really understand why that upfront investment is so important.”

Working with Potter on the preparedness team is Leah Blackwood, who has two geography degrees from USC.

The Ohio native says her interest in hurricanes was first piqued after she worked on a church missions trip in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which caused damage up and down the East Coast of the United States in 2012.

“I came home with so many questions about hurricanes, and I came home super passionate about disaster recovery, especially disaster recovery from hurricanes,” Blackwood says. “I essentially decided from there that I was super, super interested in weather, hurricanes and people recovering from them — not only the science.”

A Capstone Scholar, Blackwood double-majored in environmental science and geography before going on to work in Cutter’s lab and earning her master’s degree in geography.

In her work now for the Emergency Management Division, Blackwood helps create the state’s hurricane evacuation plan. The key for that plan is potential storm surge.

“We always say, you hide from the wind, but you run from the water,” Blackwood says. “Our infrastructure is built now to handle a lot more wind, but 2 feet of water can pick up a car and move you. That's what we care about the most.”

Her work on how storm surge will affect various communities goes into recommendations the Emergency Management Division director makes to the governor on when to order evacuations during a storm. It is that aspect of knowing her work could help save people’s lives that drives Blackwood.

“Doing hurricane preparedness at the state level and maintaining the state hurricane plan and training people on it, you know that everything that you're doing is going to be utilized,” she says. “You know that it is valuable, and you know that odds are, it's going to matter that exact year.

“Being so young and so early in my career, it just feels really empowering.”

Blackwood credits her internship opportunities at USC as well as working in Cutter’s lab with her ability to start her career as the operational planner for hurricanes for the entire state.

Through her first internship with a research office in the geography department, she met and began working for State Climatologist Hope Mizzell, who has a bachelor’s (’93), a master’s (’99) and a Ph.D. (2008) in geography from USC.

“Hope ran Climate Connections Workshops, and a lot of emergency managers would attend those,” Blackwood says. “I actually met people who are now my co-workers at an event while working for her and learned about their positions and decided that that's really what I would like to do.

“It was very humbling and intimidating to receive this job right away. And it really is my dream job, to be honest.”

Banner image: Radar image of Hurricane Hugo making landfall in Septembert 1989.