Carving a path toward justice: Part 3

History professor Bobby Donaldson addresses the meaning and historical backdrop of the George Floyd protests.

Posted on: June 5, 2020; Updated on: June 5, 2020

By Chris Horn, chorn@sc.edu, 803-777-3687

Bobby Donaldson is an associate professor of history and African American Studies and director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research at the University of South Carolina. In a three-part question-and-answer series, Donaldson presents both his scholarly insights and his personal perspective as they relate to protests over the death of George Floyd.

In the civil rights era, how did protests affect politics and elections?

In the 1940s, African Americans in South Carolina created a new political party, the Progressive Democratic Party, to challenge the whites-only state party at national conventions. When Governors Olin Johnston and Strom Thurmond championed white supremacy and refused to comply with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Smith v. Allwright banning whites-only primary elections, the Progressive Democrats brought a lawsuit. Columbia businessman George Elmore sued to force the state party to recognize his constitutional right to vote. NAACP stalwart attorney Harold Boulware successfully pleaded Mr. Elmore’s case alongside the national NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall and Robert Carter. That courtroom scene inspired Matthew Perry, who went on with Lincoln Jenkins Jr. to defend thousands of students in sit-ins, protest marches and other civil rights cases into the 1970s. Notably, J. Waties Waring, the white federal judge who decided firmly in Elmore’s favor, had been moved by the previous case of vulgar police brutality against veteran Isaac Woodard.

In 1969, activists again frustrated by the state’s dominant Democratic Party formed the United Citizens Party. The third-party power of the UCP forced the state party to run African American candidates for office. In 1970, I.S. Leevy Johnson, Herbert Fielding and James Felder became the first African American state representatives in the 20th century. In 1974, 13 African Americans gained office in the South Carolina House. In 1975, newly elected state Rep. Kay Patterson began calling on the House floor for the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the State House.

Between the 1940s and the 1970s, of course, countless people did the hard, largely unseen work of voter registration drives and voter education. We can see the effects of that in national politics today. Earlier this year, South Carolina proved pivotal in the presidential primary. James Clyburn, who endorsed Joe Biden and resuscitated a dying campaign, learned his early organizing as a student leader in the civil rights movement.

For both parties, the COVID-19 pandemic and the George Floyd movement will shape strategies and debates leading up to the November election.

"No justice, no peace" is one of the commonly seen slogans at the George Floyd protests. What were the slogans of 1960s-era civil rights demonstrations and what did they reflect?

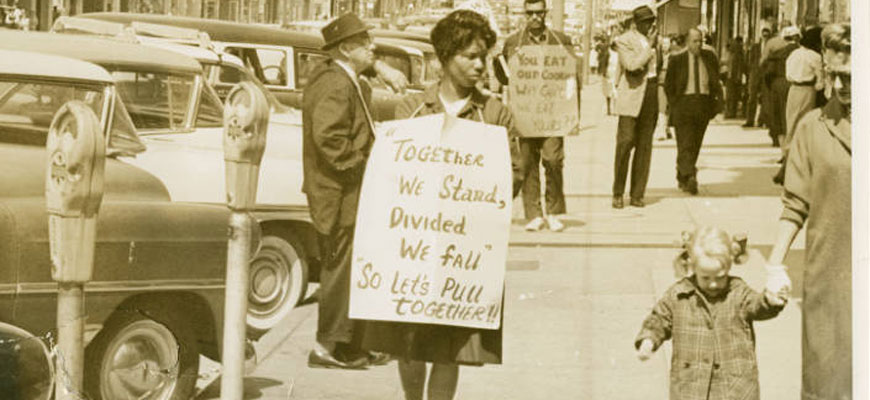

In earlier decades of activism, banners and slogans often highlighted the threat of lynching and the denial of personhood and citizenship. As we prepared the Justice for All exhibit, I made a list of the messages on the handmade posterboard signs visible in photographs and television footage in University of South Carolina archives.

Held in the hands of marchers walking two-by-two, the handwritten signs are moving and self-explanatory: “You may jail our bodies, but not our souls,” “With Liberty and Justice for All,” “Where is that Love for your Fellow man?” “Jim Crow Must Go,” “Freedom Now,” “Help! Your notions of justice are killing & threatening our morale, but not for long,” “No Color Line in Heaven,” “A New Day is coming. It won’t be long. Jim Crow has got to go. You can beat us, mistreat us, throw us in Jail, But we’ll keep traveling down Freedom’s Trail,” “God is our Guide.”

To me, the signs show the reasoned arguments of the movement (“Why shop in stores that want your money but not your company,” “Unequal protection is unconstitutional”) and the emotion (“Together we Stand, Divided we fall, So Let’s Pull together!”). Following the civil rights era, in the late 1960s and 1970s, signs and slogans often spoke of the biased employment and hiring practices and of police brutality.

The many slogans represented the multifaceted daily threat and indignities of segregation. There was not one slogan but many, handwritten, in the expressive language of each person, but the sign writing, the fliers, etc. were all deliberately organized and orchestrated. There was what I call the public movement and the hidden movement. Generally, we teach and celebrate the public movement, not giving enough attention to the hard and tedious work behind the scenes.

Yes, there were many victories, but there were enormous disappointments, terrifying violence, tragic deaths. While we shine light on the beloved community of black and white citizens singing “We Shall Overcome,” not everybody in the movement believed that.

Bobby Donaldson

Although we reference the civil rights movement as a momentous and celebrated chapter in our nation’s history, we should quickly be reminded that struggles six decades ago were regularly questioned and attacked from both sides of the political aisle. While activists and organizers were determined, the future was not easily predictable. Yes, there were many victories, but there were enormous disappointments, terrifying violence, tragic deaths. While we shine light on the beloved community of black and white citizens singing “We Shall Overcome,” not everybody in the movement believed that. While many students endorsed nonviolent strategies, many other stayed away, knowing they could not turn the other cheek if attacked. And even as we try to make sense of the current demonstrations in Columbia and around the country, let us never lose sight of the many tensions and struggles within the civil rights movement as people sought to find a way forward and to strategize about effective means to an end. There were tense moments, protracted debates, rifts and profound disagreements.

Several years ago, I worked with Mayor Steven Benjamin and others to launch Columbia SC 63 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the momentous year of 1963. We are now nearing the 60th anniversary, and, fortunately, some of the student activists are still with us. We urgently need a sustained conversation between the activists of then and now that focuses on goals, strategies, hopes, fears and frustrations.

As I speak with current and former students who marched in Columbia and elsewhere, I want them to feel emboldened, affirmed and empowered by this history. I want them to be reminded that many of those who went before were clear in their hopes of “redeeming the soul of America” — a civil rights mantra that is now used by the Joe Biden campaign. I want them to know that they walk paths that have been shaped and carved by a great cloud of witnesses and activists who dared to believe that this can be a more just and equitable nation and world.