A new likeness

Landmark photography book reissued by University of South Carolina Press

Posted on: January 6, 2020; Updated on: January 6, 2020

By Megan Sexton, msexton@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-1421

The boxes sat in the crawl space dirt, about 180 of them, stacked in darkness for nearly half a century. Inside? Some 3,000 glass plate negatives — the life’s work of Richard Samuel Roberts, photographer.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Roberts lived in the modest home at 1717 Wayne Street in Arsenal Hill, a historically African American neighborhood on the northwest side of downtown Columbia. He worked from 4 a.m. until noon as a custodian at the U.S. Post Office on Gervais Street, then walked a few blocks to his photography studio on Washington Street, where he spent the rest of the day documenting the lives of African Americans in the segregated capital city.

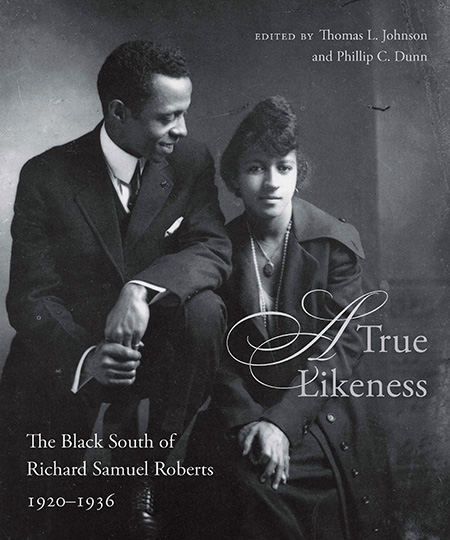

A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, edited by Thomas L. Johnson and Phillip C. Dunn, is newly available. Images provided by permission of the Estate of Richard Samuel Roberts from A True Likeness, University of South Carolina Press © 2019, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

After Roberts’ death in 1936, his photographs and glass negatives were boxed up and nearly forgotten — until the day in the late 1970s when Thomas L. Johnson, a field archivist for the South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina, interviewed a retired teacher who mentioned that an African American photographer had been her neighbor in Arsenal Hill.

Johnson was something of a scholar-detective during his tenure at South Caroliniana, tasked with helping locate and acquire valuable collections around the state to be preserved in the library. When he started working at the Caroliniana in 1973, the library was widely known for its massive holdings of plantation records, but had little that reflected African-American life in the 20th century. He was determined to address that gap.

And so he visited the Roberts family home, where Roberts’ son Cornelius still lived. That’s when he saw a number of framed family photographs lined up on the living room mantel.

“They were extraordinary,” Johnson says. “One had to be immediately struck by their stunning clarity and emotional depth. The photographs were notable for their technical finesse and stylistic polish, and yet characterized by a profound soulfulness. I had never seen anything quite like them. Roberts was obviously a stickler for perfection in terms of getting a pose just right, yet none of those pictures look posed.”

Johnson worked with Roberts’ four surviving children — Cornelius, Gerald, Beverly and Wilhelmina — to rediscover and preserve their father’s work. One fall day the group retrieved and processed the boxes of glass negatives from under the house. The collection would turn out to be one of Johnson’s largest and most significant discoveries, and one of the most valuable such collections on record anywhere.

Phillip C. Dunn, an art professor at the university who specialized in photography, was then recruited to determine whether the images on the glass plates were salvageable for printing. Dunn remembers opening the first box in the darkroom in his home, while his infant son was sleeping down the hall. The fourth negative he looked at was an image of a deceased 12-year-old boy, photographed during a wake.

“I’m looking at a picture of a dead child. I cried. I knew I had to do this right then. There was information in these negatives that people were completely unaware of,” Dunn says. “It changed my life, frankly.”

The glass plates told a story rarely seen. And the photographs showed the remarkable eye and artistry of Roberts.

“I would feel like I was standing in the darkroom with the ghost of Richard Samuel Roberts breathing on my neck, looking over my shoulder and making sure I was doing it right,” says Dunn, who was at Carolina from 1978 until his retirement in 2006.

Johnson and Dunn showed the photographs to longtime English professor Matthew Bruccoli and Rick Layman at the Bruccoli Clark Layman publishing house in Columbia. The resulting book, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts 1920-1936, was published to wide acclaim in 1986. It was featured in national and international publications, including on the front page of the London Times Literary Supplement. An exhibit of the photographs debuted in Columbia and traveled America for a decade. In 1987, Johnson and Dunn received a Lillian Smith Book Award for their work.

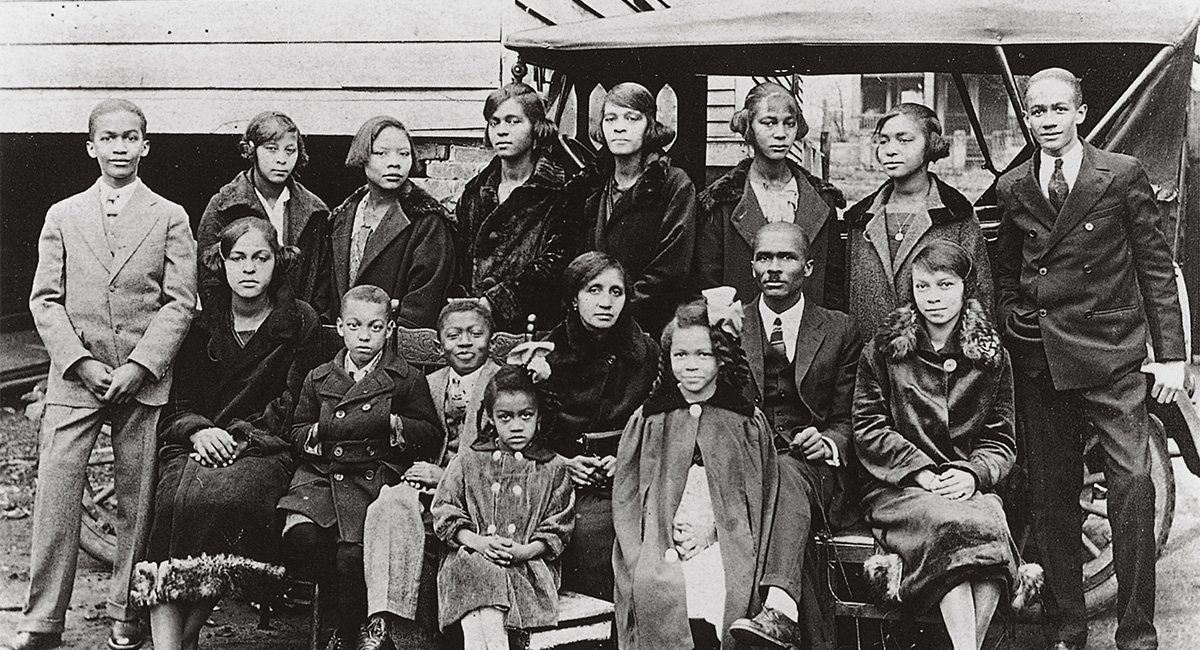

One of the most important aspects of A True Likeness, according to Johnson, is its documentation of a small black middle class in South Carolina and the South.

“Business people, undertakers, teachers, professors, mechanics and other skilled workers — the book is filled with images of those folks who were able to ‘make it,’ one might say. However, Roberts took pictures of anyone who came to him," says Johnson, who retired in 2002.

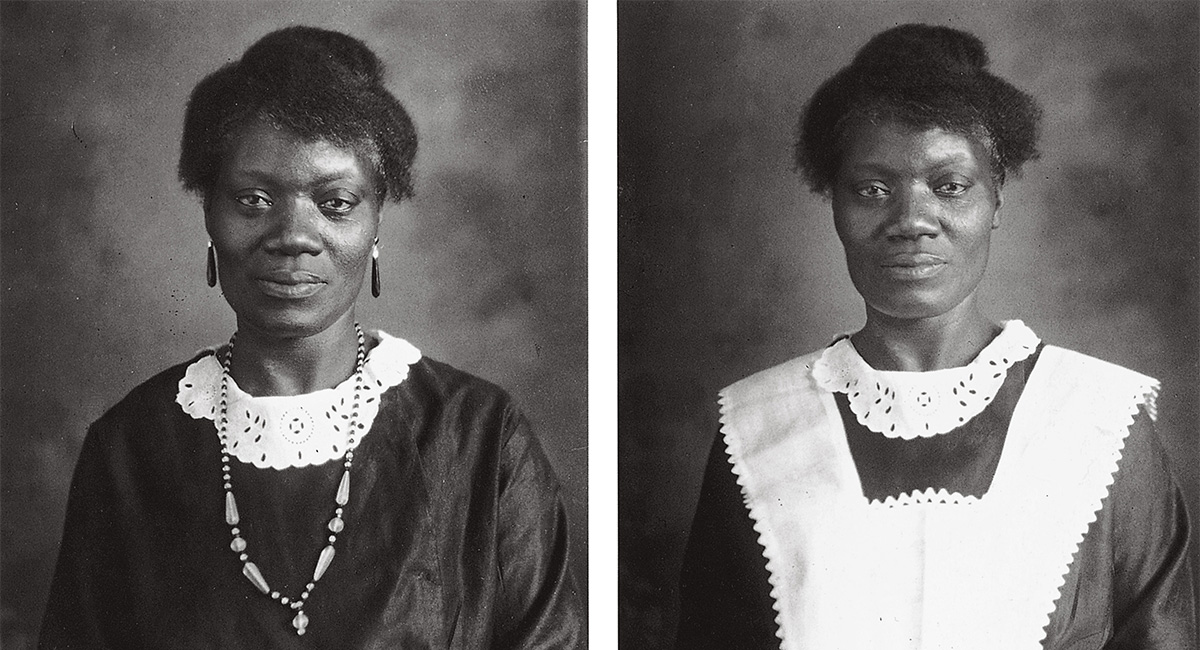

“Some images reveal in the way people are dressed that they belong to the poorest, most economically deprived segments of the black community. He was democratic — lowercase ‘d’ — in his inclusiveness, in his desire to serve everyone who came to him to have their ‘true likeness’ captured.”

Now, thanks to an expanded edition published by University of South Carolina Press, Roberts’ photographs are reaching a new audience. The 2019 edition of A True Likeness also has a different cover, additional captions, a foreword by Elaine Nichols (supervisory curator of culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture) and a new afterword by Johnson.

When Layman approached the press about publishing a new edition, the decision was easy, according to Richard Brown, director of University of South Carolina Press since 2017. The original edition was out of print, but still highly sought after, with copies selling online for hundreds of dollars.

“What Roberts did in taking these photographs was to tell stories in his own way about how life was lived in this city in a certain period of time,” Brown says. “It’s throwing a lot of light into a closet that people didn’t really appreciate before, or hadn’t seen before.”

The project also reflects the University of South Carolina Press’s commitment to issues that matter.

“It’s an important statement for the USC Press to make about its priorities and the kinds of books we think we really need to publish,” Brown says. “That means books that speak to issues around race, the African American experience, books that speak to Columbia and to South Carolina.”