UofSC archaeologist finds evidence of extinction theory

Posted on: October 22, 2019; Updated on: October 22, 2019

By Carol J.G. Ward, ward8@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-7549

A controversial theory that suggests an extraterrestrial body crashing to Earth almost 13,000 years ago caused the extinction of many large animals and a probable population decline in early humans is gaining traction from research sites around the world.

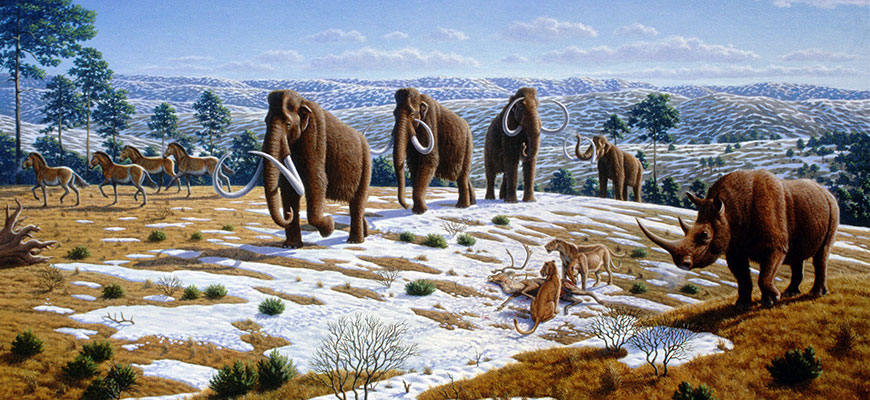

The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis, controversial from the time it was presented in 2007, proposes that an asteroid or comet hit the Earth about 12,800 years ago causing a period of extreme cooling that contributed to extinctions of more than 35 species of megafauna including giant sloths, sabre-tooth cats, mastodons and mammoths. It also coincides with a serious decline in early human populations such as the Clovis culture and is believed to have caused massive wildfires that could have blocked sunlight, causing an “impact winter” near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch.

In a new study published this week in Scientific Reports, a publication of Nature, UofSC archaeologist Christopher Moore and 16 colleagues present further evidence of a cosmic impact based on research done at White Pond near Elgin, South Carolina. The study builds on similar findings of platinum spikes — an element associated with cosmic objects like asteroids or comets — in North America, Europe, western Asia and recently in Chile and South Africa.

“We continue to find evidence and expand geographically. There have been numerous papers that have come out in the past couple of years with similar data from other sites that almost universally support the notion that there was an extraterrestrial impact or comet airburst that caused the Younger Dryas climate event,” Moore says.

Moore also was lead author on a previous paper documenting sites in North America where platinum spikes have been found and a co-author on several other papers that document elevated levels of platinum in archaeological sites, including Pilauco, Chile — the first discovery of evidence in the Southern Hemisphere.

“First, we thought it was a North American event, and then there was evidence in Europe and elsewhere that it was a Northern Hemisphere event. And now with the research in Chile and South Africa, it looks like it was probably a global event,” he says.

In addition, a team of researchers found unusually high concentrations of platinum and iridium in outwash sediments from a recently discovered crater in Greenland that could have been the impact point. Although the crater hasn’t been precisely dated yet, Moore says the possibility is good that it could be the “smoking gun” that scientists have been looking for to confirm a cosmic event. Additionally, data from South America and elsewhere suggests the event may have actually included multiple impacts and airbursts over the entire globe.

While the brief return to ice-age conditions during the Younger Dryas period has been well-documented, the reasons for it and the decline of human populations and animals have remained unclear. The impact hypothesis was proposed as a possible trigger for these abrupt climate changes that lasted about 1,400 years.

The Younger Dryas event gets its name from a wildflower, Dryas octopetala, which can tolerate cold conditions and suddenly became common in parts of Europe 12,800 years ago. The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis became controversial, Moore says, because the all-encompassing theory that a cosmic impact triggered cascading events leading to extinctions was viewed as improbable by some scientists.

“It was bold in the sense that it was trying to answer a lot of really tough questions that people have been grappling with for a long time in a single blow,” he says, adding that some researchers continue to be critical.

The conventional view has been that the failure of glacial ice dams allowed a massive release of freshwater into the north Atlantic, affecting oceanic circulation and causing the Earth to plunge into a cold climate. The Younger Dryas hypothesis simply claims that the cosmic impact was the trigger for the meltwater pulse into the oceans.

In research at White Pond in South Carolina, Moore and his colleagues used a core barrel to extract sediment samples from underneath the pond. The samples, dated to the beginning of the Younger Dryas with radiocarbon, contain a large platinum anomaly, consistent with findings from other sites, Moore says. A large soot anomaly also was found in cores from the site, indicating regional large-scale wildfires in the same time interval.

In addition, fungal spores associated with the dung of large herbivores were found to decrease at the beginning of the Younger Dryas period, suggesting a decline in ice-age megafauna beginning at the time of the impact.

“We speculate that the impact contributed to the extinction, but it wasn't the only cause. Over hunting by humans almost certainly contributed, too, as did climate change,” Moore says. “Some of these animals survived after the event, in some cases for centuries. But from the spore data at White Pond and elsewhere, it looks like some of them went extinct at the beginning of the Younger Dryas, probably as a result of the environmental disruption caused by impact-related wildfires and climate change.”

Additional evidence found at other sites in support of an extraterrestrial impact includes the discovery of meltglass, microscopic spherical particles and nanodiamonds, indicating enough heat and pressure was present to fuse materials on the Earth’s surface. Another indicator is the presence of iridium, an element associated with cosmic objects, that scientists also found in the rock layers dated 65 million years ago from an impact that caused dinosaur extinction.

While no one knows for certain why the Clovis people and iconic ice-age beasts disappeared, research by Moore and others is providing important clues as evidence builds in support of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis.

“Those are big debates that have been going on for a long time,” Moore says. “These kinds of things in science sometimes take a really long time to gain widespread acceptance. That was true for the dinosaur extinction when the idea was proposed that an impact had killed them. It was the same thing with plate tectonics. But now those ideas are completely established science.”

Illustration credit: Top image by Mauricio Antón © 2008 Public Library of Science