In the kitchen of the Still Hopes retirement community, a young man fills white ceramic ramekins with baked potato fixings: sour cream, crumbled bacon, chives, shredded cheese. Dinner prep is just one part of his job, but he prides himself on being efficient and making sure the residents have a great experience, night after night.

He learned that aspect of hospitality in his Hotel, Restaurant and Sport Management classes. He also learned the importance of communication in the workplace. “Communication is key,” he says as he discusses the relationships he’s built with his supervisor and coworkers.

The young man is a graduate of USC’s CarolinaLIFE, a nondegree, residential, inclusive program for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. CarolinaLIFE students explore their career interests and hone their employment skills through individualized coaching and access to University of South Carolina courses. On any given day, staff members might prepare them for job interviews, teach them about budgeting money or introduce them to campus organizations.

Independence looks different for each graduate. For the employee now navigating the busy kitchen at Still Hopes, it has meant living with a roommate in Columbia instead of moving back in with his parents. It has meant cooking for himself thanks to his HRSM classes. It has meant navigating the city thanks to an introduction in CarolinaLIFE’s transportation class.

When tonight’s guests arrive at the West Columbia retirement center’s dining room — there are 84 on the schedule — he will deliver their food and say hello to the regulars. And he will engage with them, which is natural for his personality and aligns with what he learned during his time at USC.

He remembers one of his very first shifts.

“They saw me and raised their hand. The man said, ‘What’s your name? I’ve never seen you,’” he explains. “And I said, ‘My name is Andro Keck, and I’m new at this.’”

Life experience

LIFE stands for Learning is For Everyone. The program traces back to USC alumnus and former Board of Trustees member Donald Bailey, ’71, who spearheaded efforts to create more postsecondary programs in South Carolina for students with developmental disabilities. Bailey’s son, Donald Bailey Jr., was a member of USC’s inaugural cohort in 2008. CarolinaLIFE was also championed by former College of Education Dean Les Sternberg after self-advocates and their parents successfully lobbied the state legislature for program start-up funds nearly 14 years ago.

One key tenet of the program is social engagement. In addition to developing meaningful friendships inside and outside CarolinaLIFE, students are also encouraged to join campus organizations.

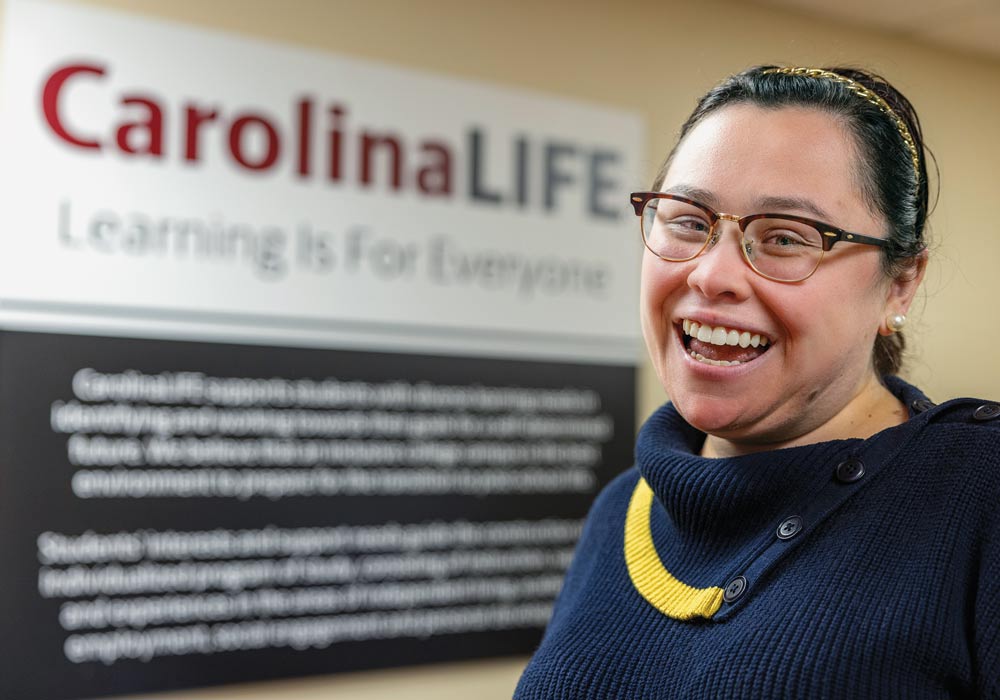

Austin native Rhiannon Dalosto, ’23, did just that when she joined USC’s color guard her sophomore year. There were a few setbacks and challenges along the way — the pandemic, a broken wrist and the day-to-day management of her type I diabetes — but through hard work and dedication, she ultimately broke an important barrier.

“My junior year, I was an alternate, so I did the halftime shows from time to time,” Dalosto says. “Then my senior year, I did everything — pregame and halftime.”

But college is also about career prep. The unemployment rate for people with disabilities is about double the rate for those without, so LIFE emphasizes career education and internship experience. That’s an added appeal to students like Dalosto.

“I’ve always wanted to help students because I know how they feel,” Dalosto says. “I want to help them go to college and actually make sure they have a chance. I want them to know that they are able to go to college because college is for everybody.”

For each of her four years at USC, she had a paid internship through the College Access and Preparation program. CAP places LIFE students in high school classrooms to mentor students with disabilities on their options after high school.

After successfully helping a student who struggled to focus, Dalosto realized she was on the right track. The internship opened the door to her current job as a ninth-grade special education paraprofessional in Hutto, Texas, where she says being disabled herself has helped students feel comfortable connecting with her.

“For me, that made an impact,” she says. “I was able to bring that with me to my new job and work with them one-on-one and be there for them and know that, OK, I’m actually doing something.”

The USC difference

Across the U.S. there are more than 350 postsecondary programs for students with intellectual disabilities. That figure is from Think College, an initiative out of the UMass Institute for Community Inclusion that provides prospective students and their families with a comprehensive program directory.

Think College is where Ruth Bollinger, ’20, turned when she began looking at colleges. Bollinger, who has high-functioning autism, had her parents’ full support. “From day one, my dad has always said, ‘Just because you have this disability doesn’t mean it has to stop you from doing the things you want to do,’” she says. “That has always stuck with me.”

None of the programs near her home in Vermont were a good fit. So she began looking in the South — specifically at schools where she could join a sorority, like her grandmother.

“I asked at each program: ‘Have you ever had a student go through the Greek system?’” says Bollinger. “Some said yes, some said no. One said, ‘Oh, we have honorary.’ And I’m like, ‘No, that’s not the same. I want to be fully initiated.’”

Among the many reasons why CarolinaLIFE felt like the right choice was its willingness to help Bollinger realize her dream. When it came time for recruitment, a staff member at CarolinaLIFE worked with USC’s Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life to ensure she could register. She was initiated into Gamma Phi Beta’s Zeta Sigma chapter, becoming the first LIFE student to join a sorority. Soon after, she became the first LIFE student to serve on a student body president’s cabinet.

Now, Bollinger’s cubicle at USC’s College of Education is covered from top to bottom with memorabilia — Gamma Phi Beta mementos, photos of friends, a Pittsburgh Penguins poster.

That’s right. Shortly after graduating, Bollinger joined CarolinaLIFE to work as a lead coach. The position is grant-funded, meaning it isn’t permanent, but it has given her the chance to help guide how the program teaches and supports students.

One of her proudest contributions at USC has been to expand CarolinaLIFE’s alumni outreach. She has created a social media group, organized regular gatherings and put together a newsletter where graduates can share life updates, like engagements and new jobs. She also coordinated with the USC Alumni Association to launch an official CarolinaLIFE chapter.

Building out the program’s alumni network has given her a front row seat for what happens after graduation. The experience is unique for each person, but one thing Bollinger can attest to is the impact LIFE has not only when it comes to skills and education, but on their confidence, too.

And together with her other job at Able South Carolina, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the lives of people with disabilities, she has been able to explore her interest in advocacy.

“It’s not about me. It’s never been about me,” she says. “I’ve always seen myself as a person who wants to help others achieve their goals, no matter where they come from or what their background is or if they have a disability or if they don’t. I want to help them in any way I can.”

Exposure and opportunity

After his shift at Still Hopes, Andro Keck enjoys the satisfaction that follows a long day’s work. His mom, Christina Keck, enjoys another kind of satisfaction, the kind that a mother feels when she knows her son has been set up to succeed.

Andro Keck helps prepare dinner in the Still Hopes kitchen.

“CarolinaLIFE had the right balance of support, exposure and opportunity,” she says. “Their goal for students to experience life and not to have their disabilities become brick walls to interacting with others truly is incomparable to anything you can do just in the home setting.”

Born in the Philippines, Andro Keck spent his first 3½ years in orphanages before being adopted. Losing out on developmental opportunities during his early years led to language deficits, and his mother worried about his options after high school. But when she and her husband found out there were options at universities within driving distance of their home in Kure Beach, North Carolina, she says, “A wave of hope just went through us.”

Some of those programs, they discovered, did not accept students under their parents’ legal guardianship, a level of independence Keck wasn’t ready for yet. Others didn’t stress independence enough. But they fell in love with USC’s program, which seemed like a perfect match for Keck, along with the staff members who interviewed him. The campus visit sealed the deal.

Christina Keck followed her son’s growth through the program at USC. Now, she sees it firsthand when her son calls with daily updates.

He still needs assistance sometimes. Several weeks ago, Mom coached him on visiting a barbershop by himself for the first time — how to make the appointment, what time to leave his apartment, what style to ask for. It’s something he wouldn’t have been comfortable doing independently just a few years ago, even with Mom’s guidance.

“He is proud of what he’s doing now, and he wants to tell us about his life,” she says. “We would not have ever been able to provide him with the opportunities to grow as a person, for him to develop his identity, to develop the level of confidence that he has, to be exposed to so many different opportunities that we cannot provide in our family setting. And every single one of those things built upon each other to help him get to where he is now.”

There are still plenty of unknowns for graduates like Keck as they navigate adulthood post-college, but he has become more and more self-sufficient, and his confidence continues to grow. He also feels more comfortable in his job. You can hear it in his voice when he reflects on his first few days, meeting new people and becoming a part of their community.

“They said, ‘Welcome to Still Hopes. I hope you stay here,’” he says. “I said, ‘Thank you. I think I will be staying here.’”

Read More: Bollingers Give Back

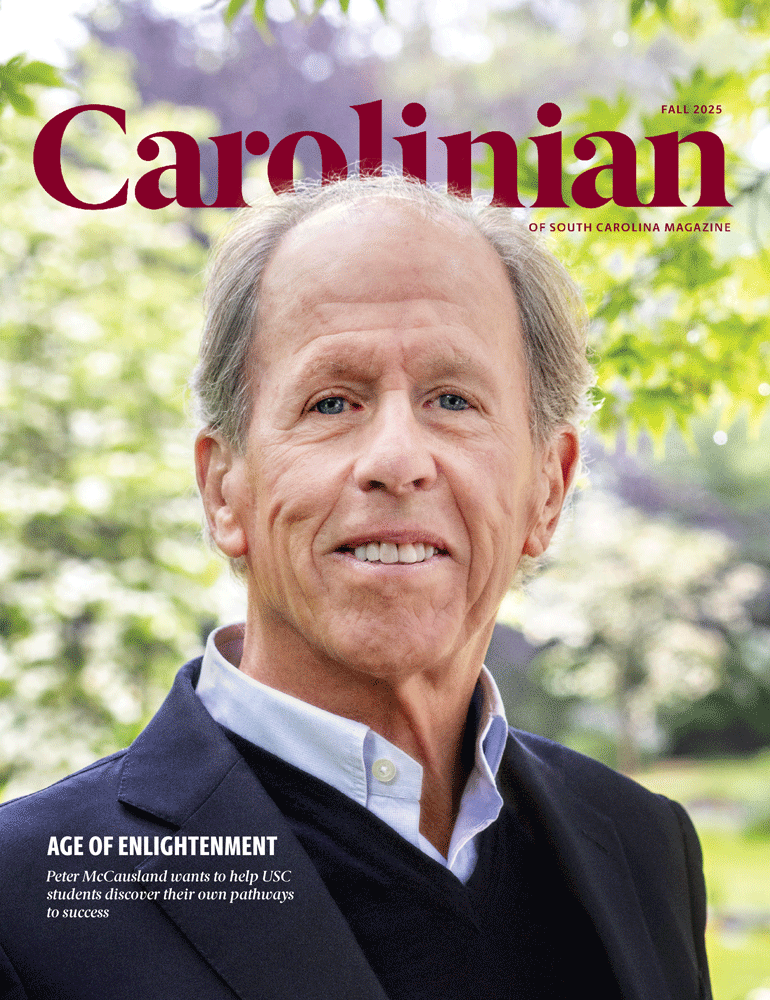

The University of South Carolina wasn’t on Dave Bollinger’s radar until his daughter, Ruth, enrolled in CarolinaLIFE. Now both Bollingers are giving back to support the next generation of USC students with intellectual disabilities.