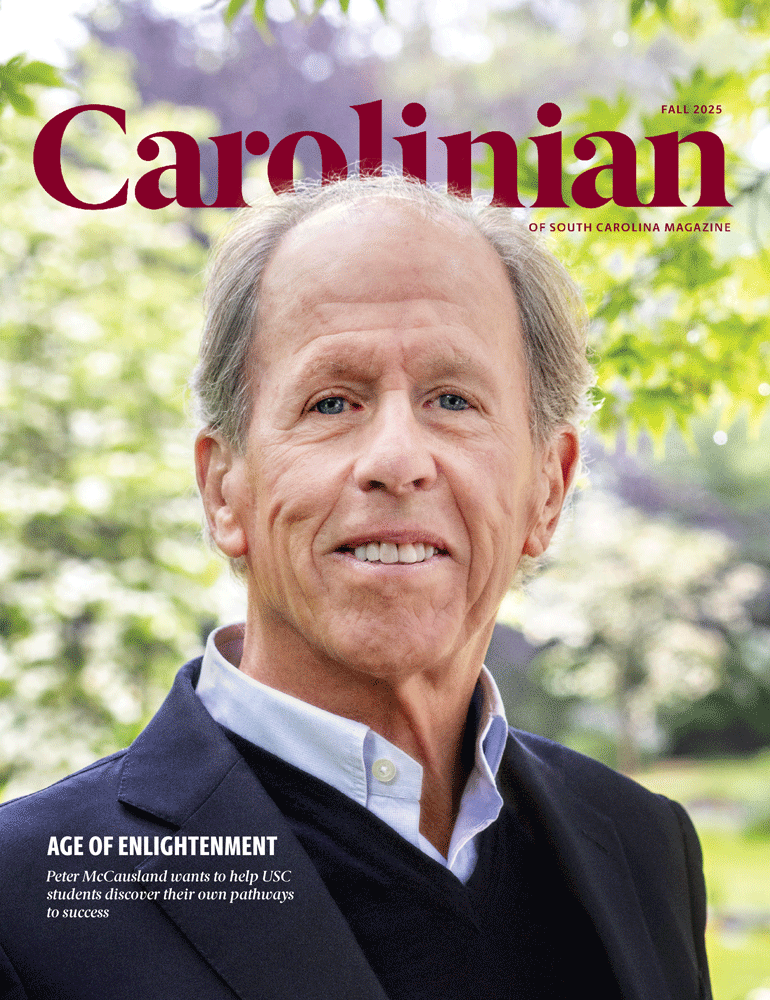

Joe Rice doesn’t walk into a room. He arrives.

Could be a conference room where he’s meeting opposing counsel. Could be a judge’s chambers. Could be a client’s home or a co-counsel’s office or his own corner office at Motley Rice, a sunlit aerie overlooking Charleston’s Cooper River and the cable-stayed majesty of the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge.

Rice is mostly a behind-the-scenes guy, not a courtroom orator. The ’76 business administration, ’79 law graduate has hammered out the deals in some of the biggest civil cases of the last quarter century, and the experience shows. He is imposing but polite. Quiet but wholly present. He carries himself just a bit like a cowboy: Confident. Calm. Cool.

Poke around: Cowhide rugs and leather chairs, cowboy hat on the bookcase, a framed photo of his beloved horse Thunder over the fireplace — all this plus a bag of William Murray Golf clubs (he’s an investor in the famous actor’s company) and a jar of Red Hot candies (his workday vice) in a modern five-story office building that is otherwise all business.

But Rice means business, too. Back in 1998, he and fellow USC alumnus Ron Motley, ’66, ’71 law, were the lead attorneys in a civil case against Big Tobacco that yielded a record $246 billion settlement on behalf of 26 state attorneys general.

Ness, Motley, Loadholdt, Richardson & Poole, the firm that brought the tobacco industry to its knees, was dissolved soon after the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, but Motley and Rice weren’t ready to hang up the boots; they hung out their shingle instead.

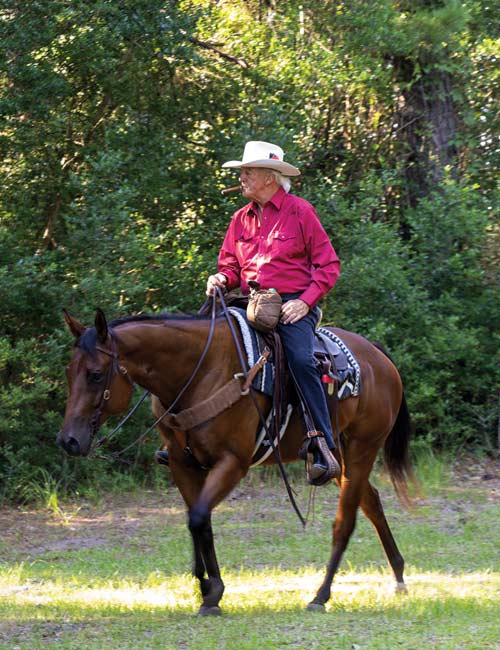

The family that rides together. Joe Rice, center, enjoys an early evening amble through the woods at Awendaw with grandson Beckett, left, and daughter, Ann E. Rice Ervin.

Since 2003, Motley Rice has taken on BP after the Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill, Volkswagen for emissions fraud, the financiers of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Big Pharma and the entire opioid supply chain — the list of opponents is as long as it is impressive. Most recently, they are building a case against social media platforms for using algorithms to target children.

Joe Rice isn’t the Lone Ranger — “You can’t do the kind of work I do without having a really good team,” he says — but even at 70, part of him still views the job in cowboy hero terms. “I guess maybe I always wanted to be the man in the white hat riding in to save the day,” he says with a grin.

When Motley passed in 2013, Rice soldiered on. The firm they started together now employs more than 120 attorneys and hundreds more support staff; it maintains offices in seven states plus the District of Columbia and has served as a springboard for countless talented lawyers who have since risen to the top of their field.

“I could have quit after tobacco. I had a lot of partners who did. But then I wouldn’t have had a chance to do the BP oil spill, or the Volkswagen cheat device, PFAS in our waters or opioids,” says Rice, sketching a quick timeline. “And if I quit now, I’m not going to have a chance to see social media through — and there’s a lot of work to be done to fix social media.”

The incentives are both personal and professional: “I tell people, ‘You work all your life to get in a situation where you can help people, to have opportunities to do good things — why quit?’”

Back in the saddle. A freak accident sidelined Rice in 2020, but he quickly bounced back. Rice’s new Western pleasure horse, Rudy, is a reliable companion.

Joe Rice emerges from the shadows at the end of the stables, sunglasses perched atop his head, readers and earbuds dangling around his neck. We’re at the family farm in Awendaw for a photo shoot, but it’s also Friday, after 5 p.m., and Rice is just back from a work trip to Cleveland.

He has fixed a happy hour cocktail in a travel mug and lit a cigar. “I have a bad habit,” he apologizes. “I smoke cigars when I ride horses.”

Awendaw is a quick shot up Highway 17 from Rice’s Patriots Point office, but the farm operates at a slower speed. On the way to the stables — or “the barn,” as the family calls the long structure at the rear of the property — we pass sheep and potbellied pigs, a goat and a bull, heritage breed chickens, ducks on a placid pond.

Rice’s daughter, Ann E. Rice Ervin, ’06, ’09 law — herself a partner at Motley Rice — is here with her and husband Tucker’s 8-year-old son, Beckett. A competitive hunter/jumper since childhood, Ann E. can’t remember a time when she didn’t ride. Beckett has also caught the bug: He competes in the Junior Looper divisions at Team Roping events and carried the American Flag at this year’s Bulls Bay Rodeo, an annual charity event Joe Rice founded to support the Hootie Intercollegiate Golf Tournament. He has the belt buckle to prove it.

“He’ll cowboy it up when you meet him,” Rice told us beforehand, and the boy does. Leaning over a stretch of fence, Beckett shows off a phone video of this spring’s rodeo triumph. “That calf didn’t just lay down there,” he says. “I put him there.”

Horses, show jumping and rodeos are as much a part of the Rice family identity as the law. After winning his first case in the early '80s, Joe Rice purchased a horse with the late Miles Loadholt, a then-colleague who later served on USC’s Board of Trustees. In the years that followed, Rice’s passion for horses kept pace with his career.

The family now keeps approximately 30 horses and enjoys summer high mountain trail rides in Telluride, Colorado. But Joe Rice also enjoys the longer, tougher haul: driving cattle across dusty plains, camping under the stars. In the late ’90s, he, his father, Don, and older brother, Donnie, joined a four-day, three-night cattle drive through the Oklahoma Panhandle. His parents’ hats now hang alongside one of his own in the barn’s well-appointed man cave.

“When I got out of law school, I wanted a way to get away from the constant need to

be reading something or doing work. I like to play golf, but I don’t like playing

golf all the time. So one of the hobbies I picked up was riding horses. Another was

riding motorcycles.”

“My dad loved to ride,” he says as he shows off a few framed photos. “He bought his first horse when he was about 60. We went on several rides together.”

Sometimes, though, Rice rides alone. During the national tobacco litigation, solitary ambles through the Francis Marion National Forest helped him recenter.

“When I got out of law school, I wanted a way to get away from the constant need to be reading something or doing work,” he says. “I like to play golf, but I don’t like playing golf all the time. So one of the hobbies I picked up was riding horses. Another was riding motorcycles.”

The order may change, but the passions stay the same. Asked in a previous interview if he’d rather be at the negotiating table, on the links or in the saddle, he offered a slightly different answer: “I would get bored if all I were doing was riding horses and playing golf.” He also enjoys target shooting, fishing and Gamecock athletics.

But horses came first. As a kid in the late ’50s and early ’60s he spent Saturday mornings in front of the TV watching westerns. Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger — his heroes were cowboys, and cowboys rode horses. He himself started with pony rides at the county fair.

“I finally rode a horse when I was 8 or 10 years old, when I lived in Lexington, North Carolina,” he recalls. “I remember Dad taking us up to the state park and riding on these follow-the-leader type horses, these real tame kind of horses.”

His skills naturally improved. He also became more attached to the horses in his growing stable. Sunny, Goldie, Thunder — he formed bonds with each. Riding became second nature. And then one afternoon in February 2020, just weeks before lockdown, something went horribly wrong.

Jami Marchant, friend, resident caretaker at Awendaw and trainer for the family’s horses, was in the ring breaking in a new one. Rice stopped by to see how the horse was coming along, asked if he was ready to ride. It was a new purchase, but no matter. Marchant had been working with the horse for a while and was impressed. Rice had been riding most of his life.

“It was a freak accident,” he says. “I’d been playing golf and had on a pair of corduroy pants instead of blue jeans. Then I got up on him and instead of just, you know, loping around a little bit, I decided to start cutting figure eights. So I’m cutting them a little faster, little faster when all of a sudden I went into a turn and — I thought we were going to turn left, he decided to turn right, and he threw me off on the left side.”

He initially didn’t think he was seriously hurt: “It just felt like I had the wind knocked out of me.” Marchant suspected it might be worse and drove him to East Cooper Medical Center for X-rays. Rice called his wife, Lisa: “I’ll be home soon.” Thirty minutes later he was on oxygen in an ambulance headed for MUSC. “Lay perfectly still,” he was told.

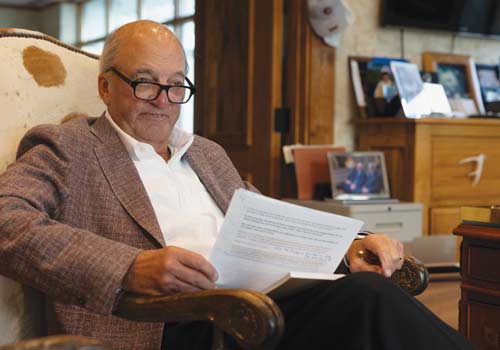

All in a day’s work. There’s always another brief to go over at the Motley Rice office in Mount Pleasant.

“I broke every rib on my left side in two places each, punctured my lung and punctured my spleen,” Rice explains. “When you break that many ribs at one time, and in that many places, in order to repair them you have to do such intensive invasion into the chest and into the back that the surgery itself is often fatal.”

Luckily, a novel procedure using new surgical instruments allowed chest wall and rib injury specialist Dr. Evert Eriksson to repair Rice’s injuries with a great deal less risk.

“I’ve got about a six-inch scar just under my left arm, and about a four-inch scar on my back, just a straight line, and that’s it,” says Rice. “They never opened me up. They never had to move my lungs around or move my heart around, which they would have had to do historically.”

But he was still concerned. As one of the lead attorneys in the battle over the marketing and overprescription of opioids, Rice knows the dangers. He wasn’t about to become a statistic in his own court filings.

“I told Dr. Eriksson, ‘Doc, I’m OK with the surgery, but I don’t want any opioids,’” he says. “And he looked at me and said, ‘Joe, you can’t survive this surgery without opioids. But I promise you, I’ll get you off of them as quickly as possible.’ And he did. We’re talking about a few days.”

Rice was discharged early with a nonrefillable prescription for Tramadol, which he alternated with Tylenol. When the dozen pills were done, that was it. Rice isn’t trying to sound like John Wayne or any of his other childhood idols; he was just heeding the cautionary tales he’d heard again and again while battling Big Pharma.

“Look,” he says. “We’ve never said that opioids are not important when used in the right way."

Happy hour. Following an after-work ride with his daughter and grandson, Rice relaxes in the barn’s man cave. His parents’ cowboy hats are prominently displayed at the center of the room.

If nothing else, Rice’s injury was well-timed. Because the surgery was performed on the eve of lockdown, his concerns about missing a significant amount of work were rendered moot. “For the first couple of weeks, I couldn’t do much,” he admits. “But then it was COVID World, and everybody was working by video, nobody was traveling, so I was not any different than anybody else.”

And now that he’s back at the office, it’s business as usual. By his own estimate, he logs about 1,800 billable hours a year, 2,400 hours overall. “I enjoy the competitive challenge,” he says. “And I like to win.”

He is also, literally, back in the saddle. At Christmas he got a new Western pleasure horse named Rudy, and while he and Rudy have yet to develop a true bond — “I’ve only ridden him six or eight times,” he says — he is glad to be riding again, even if his approach has changed.

“When I used to go trail riding in my 30s, 40s, 50s, even in my 60s, my idea was to wander through the woods on my horse and make a trail,” he says. “If I found a trail right along the highway, if I found a solid dirt road, that’s not what I wanted to do. I’d carry a little pair of clippers because I knew I was going to get tied up in the vines, but I wanted to explore and go where I wanted to go.”

It’s a choice metaphor for how he handled tobacco and every case after. “That was Ron Motley, and I trusted Ron,” he says. “I watched him develop a theme of how to use the law to correct social injustices. Then, when we were successful in tobacco, that gave me the energy and the commitment to try to do more of those things.”

In 2023, USC’s law school was christened the Joseph F. Rice School of Law. He also gave the school that now bears his name $30 million to hire faculty, provide scholarships and otherwise heighten its impact on South Carolina and the legal profession in general. He’s left a legacy, no question. But he’s not riding into the sunset.

“Everybody tells me, ‘There’s things you’ve missed along the way that you could be doing now,’ and I say, ‘I’ll give you that. I’m going to go back and do those things.’” He ticks the invisible boxes in his head: “I’m going to do more traveling. I’m going to see parts of the world I’ve never seen. But I’m also going to be here.”