On a sunny afternoon in June, Camp Cole looks like any other summer camp: Boisterous children splash in the rippling pool. The scent of sunscreen and chlorine hangs on the air.

At the nearby amphitheater, staffers prepare for that evening’s talent show. In a few hours, they’ll cart down supplies for s’mores at the campfire.

Just past the amphitheater is the 35-acre pond. Canoes glide past the opposite shore. On the dock, other campers toss fishing lines into the water while lines of ducks glide by in the distance.

But, if you look closely, Camp Cole is different from other camps, too. Instead of navigating steps into the pool, children ease into the water down a gently sloped ramp. The concrete pathways that crisscross campus are wide enough for wheelchairs. And then there’s the medical facility, complete with patient observation rooms and a nurse’s station.

That’s because the facilities are designed to be fully accessible for campers with cancer, disabilities and other life challenges.

Co-founded by 2014 University of South Carolina graduate Kelsey Sawyer Carter, the camp is named after her brother, Cole Sawyer, who died in 2004 at age 11. The camp’s logo, an old-fashioned lantern, was developed as a symbol of hope and joy for those who feel isolated and alone.

“We want to meet them where they are and connect them with families, friends and cabinmates who are going through similar situations,” Kelsey says. “We believe in shining light on our campers and their hearts.”

Rally caps for Cole

At 10 years old, Cole was an active kid who loved nothing more than being outdoors. Swimming was one of his favorite activities. He swam year-round through Gamecock Aquatics.

“That’s where we started noticing a huge difference,” Kelsey says. “Cole would warm up with at least 20 laps in the pool. And then at meets he began getting out of breath after two laps. And then I’ll never forget the bike ride where we couldn’t complete our normal loop. My mother from then on felt in her gut that something was wrong.”

She was right. At first, doctors thought it was leukemia, but eventually the diagnosis was a much rarer form of cancer: Rhabdomyosarcoma.

By Christmas, Cole was receiving multiple injections a day. He’d begun losing his hair. At one point, he developed Bell’s palsy on one side of his face. The hospital became home, and it was a tough adjustment not just for Cole, but for the whole family.

“We were really social,” Kelsey says. “And I had a lot of questions as a 12-year-old because I was frustrated that it was Halloween, and we were stuck on the fifth floor of the children's hospital.”

For the Columbia natives, Gamecock sports had always been a part of their lives. Both parents, Scott and Stacy, were alumni. The family attended every football game. Cole’s maternal grandfather even played baseball at USC and took Cole to games.

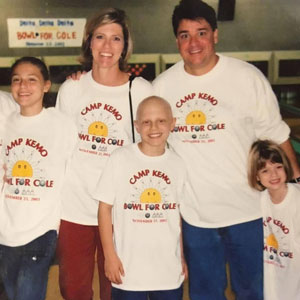

The university rallied behind Cole after he got sick. Football coach Lou Holtz joined the family for dinner and prayers. His son Skip, one of the team’s assistant coaches, also got involved. Ray Tanner, then USC’s baseball coach, became a familiar figure. Cole had visits with the basketball and football teams and even got jerseys from some of the players. Tri Delta sorority hosted a fundraiser in his honor to send other children with cancer to Camp Kemo.

Camp Kemo is a weeklong opportunity for children like Cole and their siblings to get the traditional summer camp experience. In previous years, Cole and Kelsey had done the full slate of local summer camps, including sports camps at USC. The family was worried Cole was too medically fragile for those, but Camp Kemo was doable. Cole and Kelsey were able to attend together and meet people going through the same thing.

“Cole was surrounded by other kids who had bald heads, who had ports,” Kelsey says. “I was surrounded by other kids’ siblings who were like, ‘Mom hasn't come to a soccer game all year.’ That connection just felt like home. And I got to see Cole get back in a pool. I got to see him go to the dance with a crush he had. We both got to do arts and crafts. I will be forever grateful for those memories.”

That same summer, Cole went into remission and discontinued his chemotherapy. In September, he relapsed. He died two months later.

“The cancer had taken so much from us,” Kelsey says. “Camp gave us something. It gave us so much.”

Lessons into practice

Some people cope with grief by turning inward. Some — like the Sawyers — find a way to channel it outward, to be a light for others in the wake of tragedy.

Mom Stacy and her best friend Deans Fawcett became involved with Camp Kemo, eventually serving on its board. Kelsey and younger sister Laurel became counselors. And Stacy began to dream of creating a place that could host organizations like Camp Kemo.

“Camps are phenomenal in the state of South Carolina — we have roughly 27 of them,” Kelsey says. “But the majority are built for able-bodied, healthy children. That's where we said, ‘Wait a minute. We can do better than this.’”

"Cole was surrounded by other kids who had bald heads, who had ports. I was surrounded by other kids’ siblings who were like, 'Mom hasn't come to a soccer game all year.' That connection just felt like home."

In the meantime, Kelsey earned an education degree from USC. Her classes had prepared her to understand the diversity of children — and the unique medical challenges — she might encounter in classroom, and her subsequent move to Dallas to teach allowed her to put those lessons into practice.

But then tragedy struck again. In 2016, just 12 years after losing Cole, his mother Stacy died unexpectedly of a stroke.

Kelsey realized she couldn’t let her mother’s dream die. Neither could her family friends, the Fawcetts.

“This idea of potentially building a camp for Camp Kemo one day is what really served as the inspiration behind Camp Cole,” she says. “When my mom had the stroke, the Fawcetts said, ‘We'll do it, but you’ve got to come back from Dallas. We're going to throw everything we can at this.’”

Glimmers of hope

The vision began as a place for children with cancer. But with help from Fawcett daughter Margaret Deans Fawcett, one of Kelsey’s closest friends, that vision slowly evolved.

“We kept taking it a step further,” Kelsey says. “What about children with muscular dystrophy? What about children with rare genetic disorders? How do we provide a place where their mom and dad would trust us with their most precious gift in the world?”

The Fawcett family provided a large plot of land in Eastover, about 30 minutes from downtown Columbia. When Camp Cole finally opened in 2021, it had everything a camper could ever dream of — horses, a dining hall, 13 cabins with enough bunk beds to sleep more than 200 guests.

And it has continued growing. In 2022, the camp added a turf field to make outdoor play easier for campers using wheelchairs. Construction just wrapped on a new 20,000-square-foot activities building to make year-round play possible regardless of weather. Soon, Kelsey says, they’ll finish an archway in front of the cabins.

What would Cole think if he could see it today?

“I think he would be in awe,” Kelsey says. “And then he'd be outside all day playing in the pool and kayaking.” She laughs. “I feel him out here. And my mom. I think he would be astonished at the way that his legacy is living on in the lives of hundreds of campers. We are not stopping any time soon. We're only going to grow that servitude.”

Part of that growth has meant learning to serve the populations that pass through the camp’s doors. Staff members undergo sign language training for children who are deaf and hard of hearing at Camp WonderHands and trauma training for children experiencing homelessness at Camp Impact.

The camp’s relationship with USC has continued growing, too. Sororities and fraternities hosted fundraisers to help pay for construction. Women’s basketball coach Dawn Staley donated shoes for Camp Impact participants through her nonprofit, Innersole. The College of Nursing routinely provides interns and volunteers who often stick around as program staff.

When children who have attended the camp die, their names are added to a memory garden near the pond. Adding new names is never easy for Kelsey, but they are reminders of the impact Camp Cole has had on so many families like her own.

“We're here to lift up lives and shine a light, because sometimes we're meeting them at a really dark place,” she says. “It's a really difficult job — every day looks different and brings different challenges. But it's also the most rewarding job, because if you know that you can make a difference in that child's life and provide them with that glimmer of hope, that's what it's all about.”