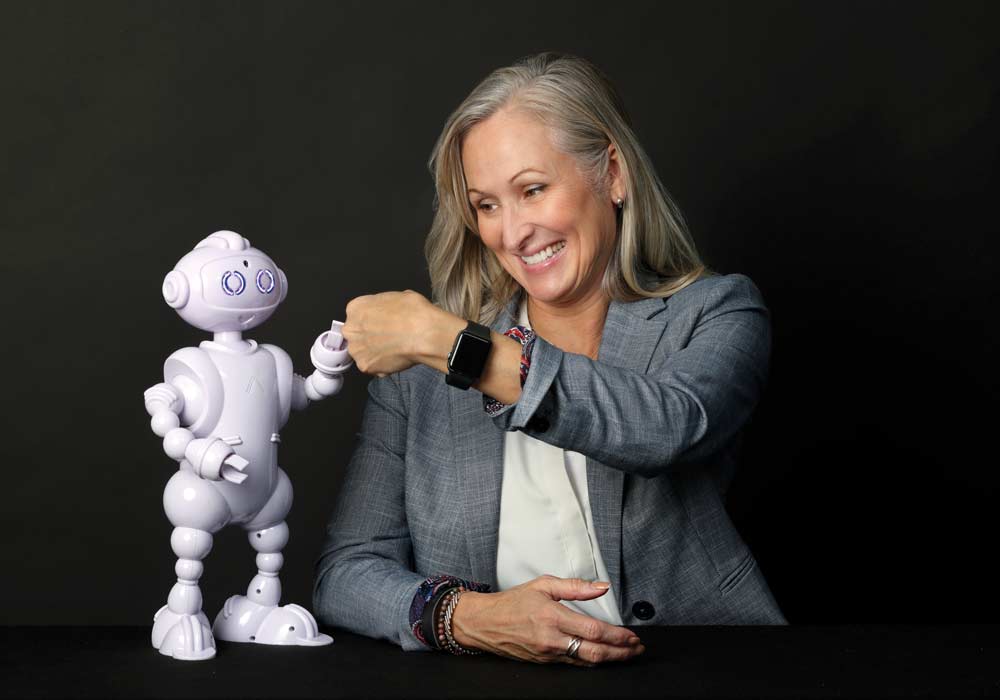

Tensions were high when Laura Boccanfuso pitched her startup to the five Shark Tank investors. Van Robotics, she explained, had developed a robot tutor that could change how students learn and retain information. ABii, an 18-inch robot that looks vaguely like a pint-sized Michelin Man, could adapt its lessons based on a child’s attentiveness and performance. It could keep students engaged, gradually building their confidence. Her ask? A $300,000 investment for a 10 percent stake in the company.

One by one, the investors provided feedback and weighed the pros and cons of supporting the company. One by one, they came to the same conclusion: “I’m out.” “I’m out.” “I’m out.” “I’m out.”

Sports mogul Mark Cuban delivered the final blow: “I’m out.”

In one sense, Laura Boccanfuso’s appearance on Shark Tank was a failure. But in the world of startups, failure isn’t always a bad thing. During her first few months of getting Van Robotics off the ground, things were touch-and-go as she struggled to line up investors and grants. It was rejection after rejection before financial support eventually came through.

And while the Sharks didn’t invest, Van Robotics got exposure for ABii. The timing couldn’t have been more fortuitous. When the episode aired in May 2020, just weeks after COVID-19 led to massive shutdowns nationwide, schools around the country were still grappling with the shift to virtual learning.

ABii guides instruction for kindergartners at Carver Elementary School in Florence, South Carolina.

“Parents were freaking out because their kids didn’t have teachers,” Boccanfuso says. “After the show aired, we got inundated with all these requests from parents who were like, ’My kid needs help. I’m not a teacher. I have to work from home. I don’t have time. Help!’”

ABii was designed for the classroom, so Boccanfuso’s team quickly pivoted: They created a version for at-home use. Parents bought a lot of robots that summer. Then Van Robotics got the attention of Time magazine, which named ABii to its Best Inventions of 2020 list. School usage grew by leaps and bounds, and ABiis found their way into classrooms worldwide. In June 2023, Boccanfuso and ABii were featured in an episode of CNN International’s The Next Frontier exploring innovative educational technologies.

“Even though we didn’t get an offer, it made all the difference because it put us on the forefront of a lot of conversations of how these things can actually help kids and teachers when they’re so strained in schools,” she says, “especially now when we have a shortage of teachers and a diversity of needs among students.”

Falling into Place

Before Van Robotics, before earning her Ph.D. from the University of South Carolina, Boccanfuso was a stay-at-home mom of three. When her youngest was old enough for school, she got the itch to go back for a doctorate in computer science — she’d earned a master’s in it from Bowling Green State several years earlier.

Her long-term goal was to teach, but after entering the program in 2008, she discovered she was also interested in robotics. Artificial intelligence was in its nascent stages, and Boccanfuso began to wonder how AI-powered robots could help children in the classroom.

The puzzle pieces were all there. The question was how they fit together. Then Scientific American published Bill Gates’ seminal “A Robot in Every Home,” an essay that predicted the coming ubiquity of household robots. Suddenly, the pieces began falling into place.

“People were starting to study using robots with AI to support kids with autism or kids struggling with social-emotional skills and communication,” she says. “I thought, ’That’s it. There it is. A robot in every classroom.’ Why not? I mean, if a robot in every home is feasible, a robot in every classroom is even more feasible and maybe a little closer to reality than we were at that time.”

She explored the idea further while doing a postdoc in social robotics at Yale. During her free time, she began building the software. By the time she launched Van Robotics in 2017, she had nine lessons, working software and a sketch of ABii that would soon become a 3D-printed prototype.

“I was like, ’I’ve got to start this company,’” she says. “Nobody else is doing this. It’s a huge risk. But if I don’t do it, nobody else will.”

Many aspiring roboticists relocate to Silicon Valley, Boston or Austin, but Boccanfuso was reluctant to uproot her family again. She finally decided to bring Van Robotics to Columbia based on sage advice from MongoDB and Business Insider founder Kevin Ryan, who she met through a Yale venture creation program.

“He goes, ’Look, move to a place where you’re most comfortable. Move to a place where you’re happiest. Make your location your home, the place where you want to be, the place where you feel great, because you can find people, you can recruit people, you can find resources.”

Fist Bumps and Rainbow Eyes

At the back of Melissa Marsik’s third-grade classroom at Carver Elementary School in Florence, South Carolina, two students work through lessons on laptops. Animated versions of ABii guide their instruction. Overlooking the laptops are two more ABiis — actual infant-sized robots with modular arms and legs and ring-shaped eyes that light up.

Students wiggle excitedly and raise their hands to share what they like about their robot tutors. “I like doing harder lessons so I don’t have to work on a third-grade level anymore,” says one child.

“Some of them are learning about decimals, which is not a third-grade standard,” Marsik explains. “Some of them are learning about higher-level multiplication. We usually do single digit by single digit, but they’re now working on multi-digit multiplication, which is fourth-grade standard.”

Two students say they like what ABii does at the completion of each lesson. Sometimes the robot dances and invites them to join in. Sometimes its eyes light up with flashing rainbow colors. Other times, it gives fist bumps.

“Sometimes I don’t even notice they have rainbow eyes,” Marsik says. “And the class will be like, ’Oh, Tinsley got rainbow eyes!’ So they get excited for each other, too.”

The ABii curriculum covers reading, math and social-emotional learning. Students are given a pre-assessment at the beginning of each lesson; if they don’t pass, a tutorial catches them up. Sometimes the onscreen ABii blasts into space, sometimes other animated robots join the storyline. And while students work on the computer, the ABii robot next to them monitors their attention levels. If their focus starts to fade, ABii offers them a break to recharge. Teachers monitor performance and attention through daily reports.

It’s not just about attention span and engagement, though. It’s also about rigor, and it’s about customizing that rigor to the needs of individual students.

ABii’s animated friends each struggle with common learning barriers that students can solve during lessons.

“There are kids who are ready to advance, and then there are kids who are struggling, and we need to be able to have a classroom that is equipped to handle both and all of those situations,” Boccanfuso says. “Instead of continuing learning as sort of a continuum across a single plane, we have to think about it as being multidimensional for different kids.”

And it’s OK if students struggle a little bit. In fact, it’s part of the learning process, something Boccanfuso knows firsthand from her experience launching a startup.

“Everyone will struggle at some point if they’re doing challenging enough work. If you’re not struggling, that’s an indicator you’re not doing challenging enough work,” she says. “Maybe you need to do something harder. But the struggle is real, and it’s OK. It’s OK to fail.”

Fit for the Future

Since October, Marsik’s district has been integrating ABii into its elementary schools. Students aren’t the only ones who have embraced the new robots. According to Florence 1 STEM Director Chris Rogers, teachers have also enjoyed the flexibility of ABii’s curriculum and the ease with which students can work with minimal oversight.

“Teachers can assign lessons or just put a kid on their grade level and let ABii do its thing,” Rogers says. “Or the teacher can say, ‘Oh, we’re studying this this week. I want to make sure ABii is reinforcing that.’ It’s all related to our South Carolina standards, so it works really well with what they’re teaching.”

Even though the curriculum only goes up to fifth grade, Florence 1 has begun integrating ABii into middle schools, too, thanks to Van Robotics’ Classroom to Career program, which teaches older kids how to build the robots. This year, the district’s middle schoolers built 40 ABiis for use in K-5 classrooms.

There is evidence to suggest it’s working. A study funded by a grant from the South Carolina Department of Education showed marked test score gains in students who used ABii compared to those who used other software. While Florence is still new to the robot tutors, Rogers is optimistic that the technology holds promise for improving student learning.

“I think it’s a good happy medium of starting to figure out where AI can fit at an elementary school,” Rogers says. “Where will it do best? We’re kind of learning that like everybody. And I think ABii is a great place to start to learn about AI and see what it can do. How far is it going to take us in the future?”