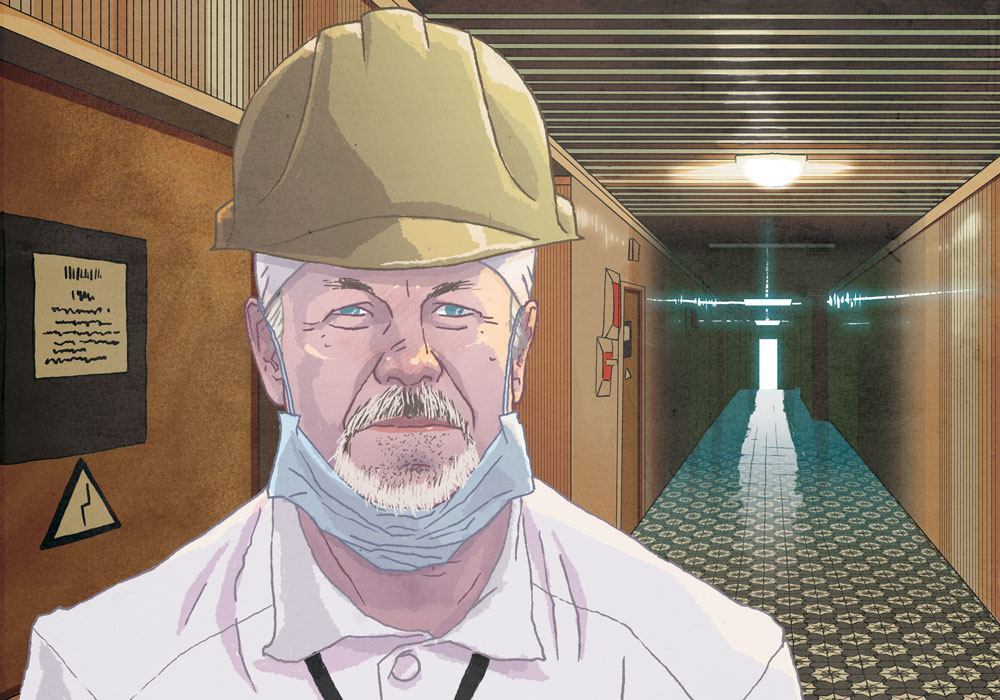

It’s Oct. 8, 2022, and Tim Mousseau is staring down a very long hallway. He’s wearing a hazmat suit, goggles and gloves, yellow booties over tight-laced boots. He’s breathing through a respirator. The eerie golden panels on either wall reflect the dull fluorescent lights in the ceiling. In the distance — maybe 600 meters ahead — lie the ruins of Reactor No. 4.

Welcome to Chernobyl, site of the world’s largest-ever nuclear disaster. It’s been 36 years since the reactor at the end of the so-called Golden Corridor melted down, and the temporary sarcophagus built to cover it in 1986 is itself now contained within a second 32,000-ton structure, the New Safe Confinement, completed in 2016.

But don’t kid yourself: This remains one of the most toxic places on Earth. Under all that concrete, steel and expert engineering lie an estimated 200 tons of molten corium, 16 tons of uranium and plutonium, and plenty of radioactive dust. And while the toxins at the plant are sequestered, hazards remain. Fallout from the accident contaminated the soil, water and food supply throughout the 1,160-square-mile Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, affecting all manner of living organisms then, now and for centuries to come.

Which is, in fact, the draw. An evolutionary biologist, Mousseau has been studying the effects of ionizing radiation on wildlife at Chernobyl for two decades. Pre-pandemic, he made the trek from his lab at USC to his field lab in northwestern Ukraine a few times a year. And while the Russian invasion in February 2022 further delayed his return, once the war shifted east, he packed a suitcase. “You know, I’ve got my lab there, I’ve got a house, and I’ve got equipment,” he says. “I’ve got ongoing studies. If you don’t show up regularly, nothing gets done.”

Did he need to stare into the nuclear abyss to continue that research? Probably not. But when you’ve devoted so much of your career to studying the effects of the disaster, you don’t turn down the tour.

“Discovery, obviously, is my major driver. Discovery and exploration. That’s what I’ve always done. That’s why we do what we do.”

“VIPs and people with money to get in get shown the Reactor 1 control panel, which is the same as all of them but wasn’t disturbed by the accident,” says Mousseau. “But people who are really interested in the topic want to see Reactor 4. Almost no one gets to see Reactor 4. Since Covid-19, at least, no one had been there except for the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, who’d visited a few months earlier.”

The rest of the Exclusion Zone is another matter. In recent years, the once-off limits area around Chernobyl has become a mecca for "dark tourism."

Day-trippers flood the zone aboard tour buses from Kyiv. Many are gamers, says Mousseau, eager to see the wasteland depicted in S.T.A.L.K.E.R, a first-person shooter video game set at Chernobyl. They visit Pripyat, the nearby ghost town where Chernobyl’s workers lived prior to the accident. They gawk at overgrown Soviet-era apartment blocks and what’s left of the city’s amusement park. They take selfies among the ruins.

But that’s not Mousseau. The man staring down the Golden Corridor is one of USC’s leading researchers, a former associate vice president for research, graduate school dean and associate dean for research and graduate education. He’s a renowned scientist with a CV to match, not a thrill-seeking apocalypse junkie.

“The opportunity at Chernobyl for an evolutionary biologist, which is the prime conceptual context for everything that I do — it’s unique,” he says. “Every rock we turn over generates some new insight that’s never been touched upon before.”

Into the zone

It started with birds. Scratch that. It started as a lark, Mousseau’s word.

In 1999, USC law school alumnus and donor Bill Murray, ’48, funded a goodwill trip to Chernobyl for several university faculty. Naturalist Rudy Mancke and biology professor James Morris signed on. So did future Arnold School of Public Health Dean Tommy Chandler. Mousseau joined the trip because, well, why not? “It really was kind of a lark,” he says. “It was just, you know, ‘Let’s go see it.’”

Barn swallows were among the first wildlife studied by Mousseau and his colleagues at Chernobyl.

But the trip made an impact. The next year, Mousseau was on sabbatical in France with another biologist who had himself visited Chernobyl. As the two discussed their experiences, it became clear they needed to go back.

“We decided, ‘What better place to look for the effects of increased mutation rates?’” says Mousseau. “We know radiation increases mutation rates — people have gotten Nobel Prizes for that — so let’s see if we can see their effects at an ecological scale. Most of the other studies have been done in the lab, you know, zapping things. This was a lab too, but a real-world lab.”

The project started small — Mousseau calls it “kind of a hobby thing.” He and his colleagues would go for a week or two every year to catch birds, take measurements and samples, write a couple papers. But before long, they started to get traction. “The research was getting a lot more attention than we expected,” he says. “There was a huge pent-up interest in these questions, so we ramped it up, and it snowballed into a large number of different projects.”

They looked at cataracts, which are more common among birds exposed to radiation. They looked at fertility and developmental abnormalities. They looked at species populations, feather development, tumor growth and a range of other factors that demonstrate genetic damage. They measured the heads of birds and noticed the diminishing size of their brains.

“We collected data on brain size based on head size measurements for 48 species of birds,” says Mousseau. “But we also measured rodents — voles and mice — and found the same thing, basically smaller brains in the more radioactive areas. This is totally consistent with what we know about the effects of radiation on developing neurons, that neurological development is very vulnerable to ionizing radiation and oxidative stress in general.”

The findings were also consistent with outcomes at Hiroshima, Japan, where high doses of radiation caused mutations in embryos that led to microencephaly, smaller heads and other developmental abnormalities among children born after the atomic bomb. But Mousseau’s findings in the Exclusion Zone were controversial. “It’s just that no one expected this at Chernobyl,” he says. “Some of the nuclear safety folks had been suggesting that radiation levels were just too low to be seeing these kinds of effects.”

Another major discovery from Chernobyl involved the compounding effect of multiple stressors (think: harsh weather, strenuous migration) that put organisms at greater risk.

“Critters living in the wild have a much tougher time, not surprisingly, than critters living in a lab,” Mousseau explains. “When you combine multiple stressors, there’s often a synergy that makes a new stressor like radiation much stronger than you would predict based on laboratory studies. At Chernobyl, there have been enough studies now to know that an organism is about 8.6 times more vulnerable to the effects of radiation overall.”

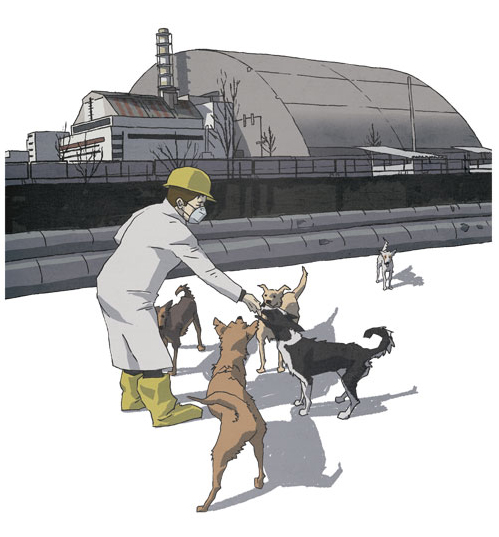

Dogs of Chernobyl

Next came the dogs, which started not as a lark but a good deed.

Chernobyl is home to a large feral dog population. They tend to congregate around the plant, where they are fed scraps by workers and tourists. Over time, the dogs became a popular attraction, but left unchecked they also became a problem.

“Even feral dogs become very friendly when you have food,” says Mousseau. “As a result, the dog population got way out of control. There were over 800 dogs around the power plant by 2017.”

Eventually, plant officials brought in an NGO to run a spay and neuter clinic. Mousseau got involved because it was a good cause, but he also had another motive. “My main interest was in getting DNA samples from a new system,” he says. “Dogs, as it turns out, are a fabulous model for human disease — they get the same cancers we do — and these dogs were living in the most radioactive part of the zone. Plus, I now had a team of 25 folks to go out and catch them for me.”

While the dogs were sedated, Mousseau took blood samples and saliva swabs, which he brought back to the U.S. The work stalled when Covid-19 closed the borders, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 further delayed his return. But after the fighting shifted east, he got word that it was safe to resume the project. “We also started getting photos from the power plant and other NGOs of dogs with their rib cages showing,” he says. “It was pretty terrible. They’re just domesticated enough to not be able to fend for themselves and find their own food sources.”

Mousseau and several veterinarians from around the world finally reconverged on Chernobyl in September 2022. Over five long days, they sterilized and took samples from 125 dogs. Between 2017 and 2022, he estimates that he took 800 samples, and that at least 600 are of good enough quality to study. The question was how.

“I collected all these samples, some from hot places, some from normal places, and I’m trying to figure out, ‘What the heck do I do with them?’” Then he had an epiphany. “I thought, ‘You know, I know what I want to do. I want to do whole genome sequencing.’”

The dogs, he suspected, might be descendants of dogs abandoned at the time of the accident. If he could prove it through genomic sequencing, it could shed new light on radiation’s effects on humans.

But first he needed a collaborator — not to mention funding — so he tracked down Elaine Ostrander at the National Institutes of Health. Ostrander made her name studying cancers, notably prostate cancer, and uses dogs as her research model. She is also well versed in the evolution of dogs, making her an ideal partner. NIH not only agreed to run the genomic sequencing, Ostrander brought on one of Mousseau’s doctoral candidates, Gabriella Spatola, as an embed.

“So we’re doing whole genome assays for the birds, barn swallows primarily, and we’re doing it now with dogs as well,” says Mousseau. “This lab at NIH is the premier dog genomics lab in the world. It’s just incredible.”

Other labs, other worlds

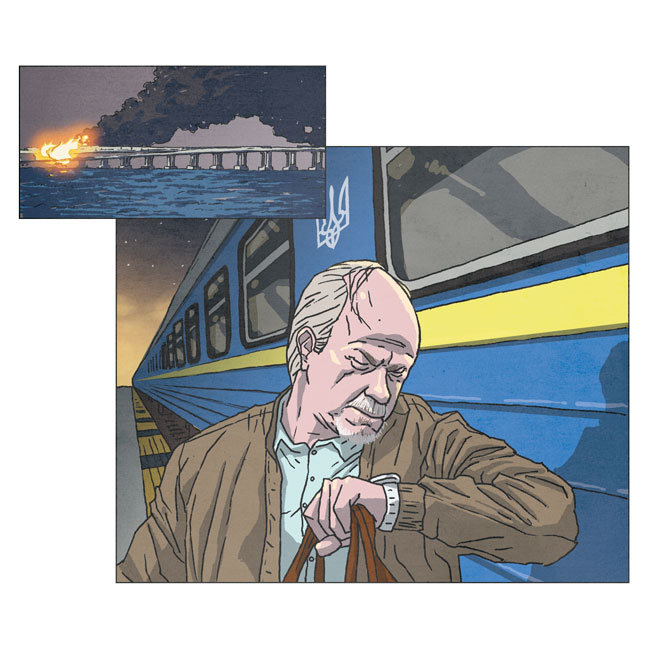

It’s Oct. 8, 2022, and Tim Mousseau has emerged from the Golden Corridor. After three years away — after two decades of research — it’s a defining moment, one made all the more salient by the ongoing war.

In fact, the war feels closer than it has since he arrived. There are suddenly more tanks and armored cars in the area, more soldiers at the checkpoints. Something’s not right, he thinks. Then he hears the news.

That morning, an explosion destroyed part of the Kerch Strait Bridge in Crimea. It’s unclear who is responsible, but it’s clearly significant. The bridge, completed just a few years earlier, is a source of pride for Russian President Vladimir Putin — and now it had been attacked just one day after Putin’s 70th birthday.

“We realized there was going to be some retribution,” says Mousseau. “All of a sudden there’s military coming out of the woodwork. The Ukrainians knew what was coming and they were gearing up. So, after we finished our tour, we headed straight to the train station. We had dinner and got on the midnight train to Warsaw. The next morning the bombs started raining down.”

Now safely back on the USC campus, he’s unsure when or even if he’ll return to his lab-away-from-home. It’s a chance to assess the work he has done over the past 23 years, but the reflection is tinged with sadness. “Ukraine has become a central part of my life,” he says. “And it’s about more than my research — Ukrainians are such warm people, so to see what’s happening, that’s the real tragedy.”

But the work marches on. Students in his lab monitor surveillance footage from the Chernobyl woods, tracking population densities of deer, moose and other wildlife. Meanwhile, Mousseau follows the research where it takes him, conducting studies, collecting samples, revising our understanding of genetic variation.

Due to lingering Covid-19 restrictions, he can’t get back to Fukushima, Japan, where he has conducted a sort of sister project on the effects of radiation, but he has dog genome projects underway in Belize, Fiji and the Marshall Islands. He recently returned from Saint Croix, then jetted off to Cambodia. He’s planning a trip to Kazakhstan.

In 2022, the globetrotting biologist’s emerging interest in dog genomics even took him to the Galápagos Islands, where Charles Darwin’s observation of finches inspired his theory of evolution in the 19th century.

“I tell my graduate students, being a tenured full professor at an American Research I university is the greatest job in the world because you can pursue so many things in combination,” he says. “As long as you produce quality work, you can pursue what you want.”

And produce they do. In March, Spatola, Mousseau and few other researchers from the team published initial findings from the dog genome project in Science Advances, a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The story was quickly picked up by the New York Times.

According to Mousseau, the article presents strong evidence that the dogs around the plant are, indeed, descendants of dogs abandoned in 1986, paving the way for an array of important new research.

“The collection of samples that we have from 2017, 2018, 2019 and now 2022, provide one of the most promising tools yet for the study of radiation effects on animals,” he says. “Such studies are likely to be of great relevance for human populations exposed to radiation.”

For Mousseau, it’s all connected, and there’s always another real-world lab, always another horizon.

“Discovery, obviously, is my major driver,” he says. “Discovery and exploration. That’s what I’ve always done. That’s why we do what we do.”