If you followed Gamecock football during the Lou Holtz era, you might remember defensive tackles Langston Moore and Preston Thorne. Moore made a big impact on the field, getting drafted in the sixth round by the Cincinnati Bengals in 2003; Thorne made his big impact after graduation, becoming a social studies teacher and coach at Blythewood High School.

Each was successful in his own way. By their early 30s, though, the onetime teammates were looking for the next chapter. They found it, quite literally, as children’s book authors.

You read that right. Now read it again. Two former Gamecock bruisers who lettered in leveling their opponents now write picture books for third-graders.

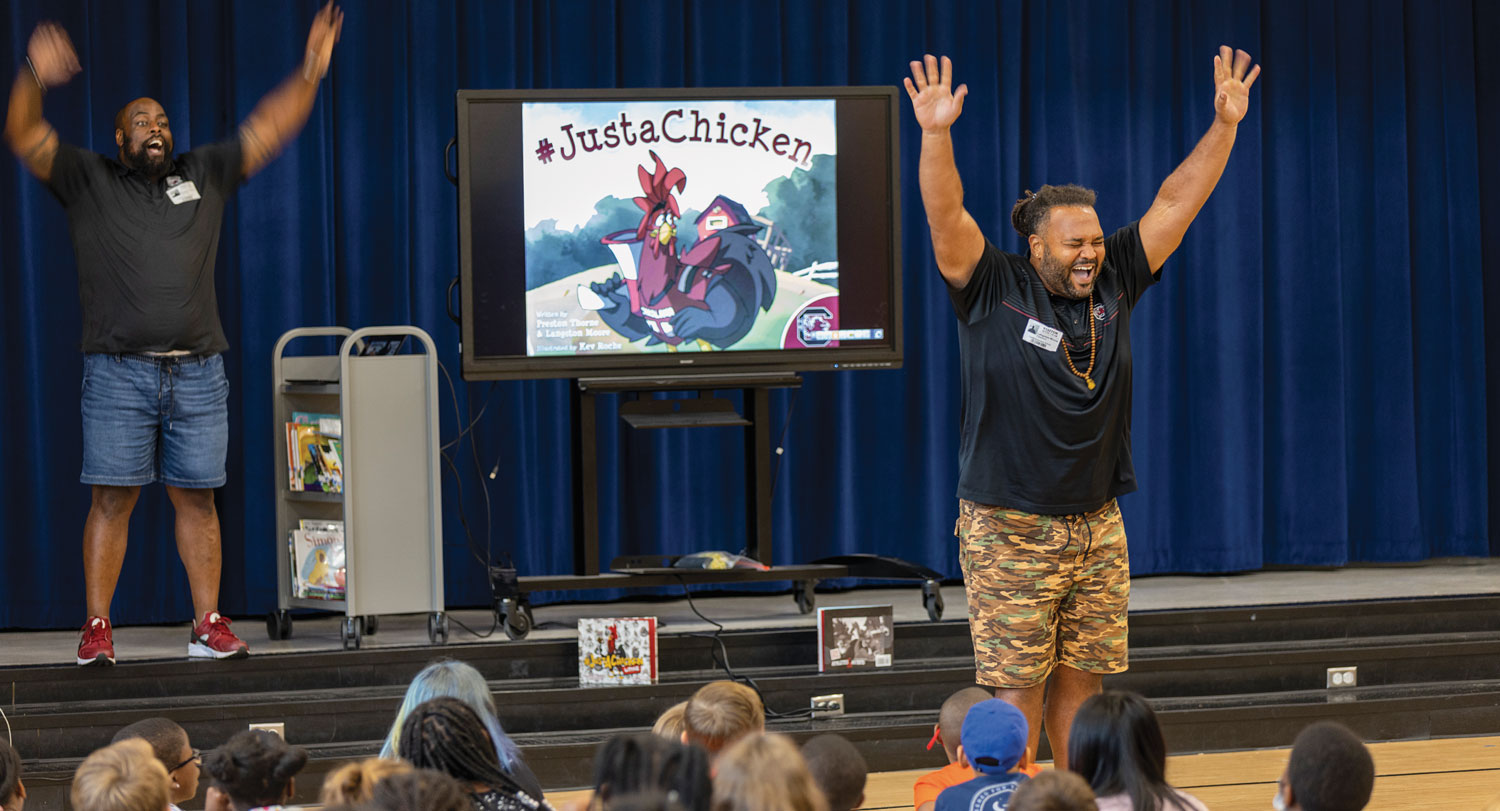

Their first book, #JustaChicken, follows USC mascot Cocky’s transformation from a timid chicken with low self-esteem to a proud Gamecock. Since then, the duo has written two follow-ups — #JustaChickenLittle and #UstaWuzARooster. All three books are illustrated by alumnus and ESPN illustrator Kev Roché, ’05.

“It started out as us wanting to write one of these big leadership books,” says Thorne, ’04. “We played under Lou Holtz, and he had all these ideas about leadership. Then as 30-year-olds we discovered that we didn’t know as much as we thought!”

What they do know is how to connect with kids. Since 2015, Moore and Thorne have taken #JustaChicken to more than 300 schools across South Carolina, promoting literacy and sharing life lessons, and the response has been overwhelming.

When they walk into a school gymnasium, they’re greeted with cheers from kids who have heard they played football in college, or in Moore’s case, the NFL. When they walk out of a classroom, they’re congratulated by teachers and administrators who appreciate their message, energy and commitment.

“What I love about them is their story. They’re incredibly personable and they’ve got that hook to pull these kids in,” says Seven Oaks Elementary School Principal Christian English, M.E.D ’14. “They’re football players and they’re authors. They connect with these students, especially young men, and just get them engaged, help them understand that reading is fun.”

They also emphasize long-range goals, especially with older students focused exclusively on end zones.

“I have a lot of friends who, for them, football is their whole life. But as we say, NFL stands for ‘Not for Long,’” says Moore, ’03, who was released by the Bengals in 2009. “So what happens when you do get there, and you do have some success, but then it’s over?”

Backpack ballet

Langston Moore loves to talk football — when kids ask him about the NFL, he gives them the good, the bad and the 5 a.m. practice. But when he and Thorne visit schools, they mostly talk about the future, which begins with their childhoods.

Moore grew up watching his father, Ken Moore, ’75 journalism, write and edit radio scripts, and he credits his mother, Stephanie Sexton, for his nimble feet. As he explains, Mom wouldn’t let him play football until high school — despite his size, his athleticism and every other indicator — and signed him up instead for ballet and tap.

As he shares the story with a fourth-grade class at Seven Oaks Elementary, the HRSM grad bounces a bit, tap dancer toes under a lineman’s body. He tugs the straps on his backpack and hangs his head. Just a chicken? Maybe, but just for a second. When the kids bust out laughing, he bolts up straight. He’s not angry — the twinkle in his eye betrays a sense of humor — but his voice is ALL COACH.

“What?” he snaps at a giggling boy upfront. “Why’d you turn your head like that?” But then his voice softens: “Listen, this is how smart your parents are. When I got drafted into the NFL, the very first place they took us was to a ballet and Pilates class. The very same stuff my mom had me doing in third grade and fifth grade helped me later in life.”

But Mom and Dad weren’t Moore’s only influences. The Charleston native can rattle off plenty of mentors, from his James Island classroom to USC to his seven seasons in the NFL.

“People tell me, ‘Man, you’re lucky to have those athletic skills,’ and I am, I got a lottery ticket, but I always tell them where I was really lucky was that I was around different positive examples my whole life: Different men. Different Black men. Different teachers. That gave me the space to do other things and be creative.”

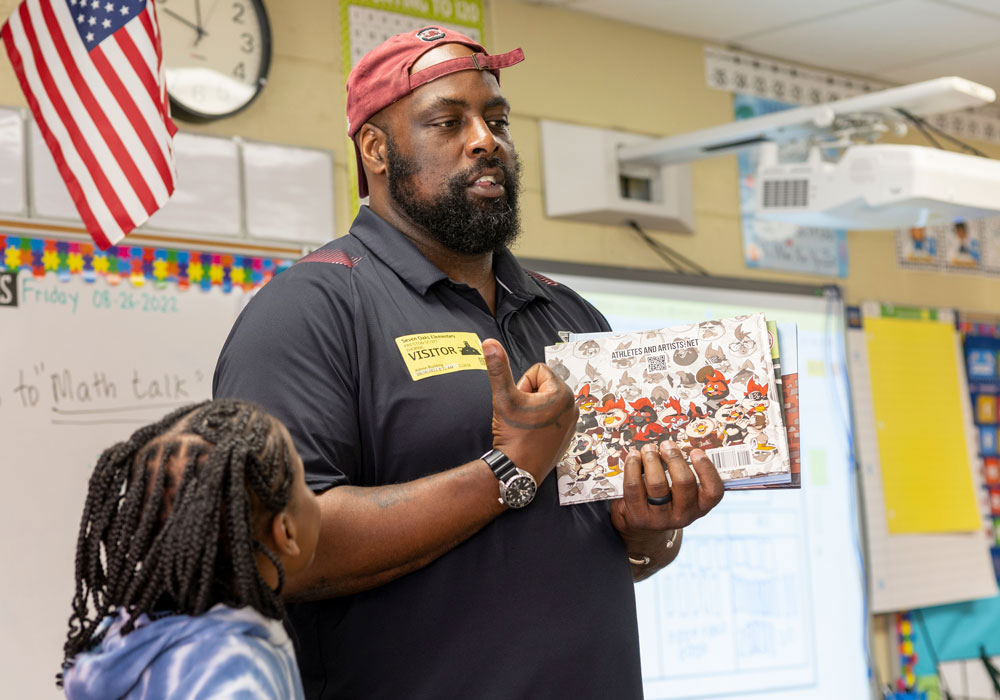

Creativity is a keyword, especially in the breakout sessions. When a language arts teacher asks where they get the ideas for their books, Moore reaches into his backpack.

“They’re all around us,” he tells the class as he pulls out a notebook. “Anytime I have an idea I just write it down.” He opens the notebook so the kids can see. “You can tell I can’t draw that well — look at this chicken I tried to draw! — but it doesn’t matter. The point is, write it down. If something gets you excited, write it down.”

It’s not all chicken scratch. Since retiring from the NFL, Moore has channeled his creativity into a range of opportunities. In addition to author and public speaker, he has worked as a sideline reporter for the Gamecock IMG Network and as a real estate investor.

Unlike football, he explains, there are no rules now other than the ones he and Thorne create for themselves. They want to remain authentic. Their presentations need to be pedagogically sound. Otherwise, anything goes.

“It’s all about creating options,” he says. “It’s a lot better than just saying, ‘I play football and that’s all I can do.’ It’s like we tell the kids: ‘You can have a major influence on how you want the story of your life to be told. Figure out what you want, get creative, then find other people out there who are doing what you want to do.' "

Bait and switch

Preston Thorne came to his crossroads early when he blew out his knee. But football was never the only plan. Thorne is a student of the game — you can still hear him talk about the game on 107.5 The Game, where he co-hosts The Extra Point with Pearson Fowler — but at USC he was just as focused on academics. He majored in history and regularly made the dean’s list.

It’s a point of pride, something to bring up when he’s connecting dots. “I enjoy reading about sports,” he says when the kids ask about his favorite books. “If you come to my house, you’ll see two whole shelves of books about sports. And history. I love to read about history, too. I have a history degree.”

Hands go up. Thorne nods, smiles big. The kids have more questions, but they want to talk about their own interests, too. He can tell. He’s done this before.

“Whose favorite subject is math?” he asks, and a couple hands shoot up. “Who loves English?” A couple more. “Who loves… science?” A little girl in the back is bouncing so hard in her seat she practically touches the ceiling. “Well guess what? When you get to college, you get to take classes in all the things you really, really love,” he says. “That’s when I really started loving my classes.”

It’s true and not true. Thorne was always a serious student. Growing up he dreamed of football glory, but he ultimately saw himself in the classroom. Or on the sidelines. Or both.

And that’s where he landed, teaching and coaching at Blythewood High for 11 years. For the past five he has been with the College of Education at USC, where he directs the Apple Core Initiative, a scholarship program designed to recruit, retain and deploy teachers to underserved and underrepresented communities. He also continues to do some instruction in Richland School District Two.

“I had really awesome coaches, and I got a great education at Summerville High School, so I wanted to teach African-American studies in high school,” he says. “And I wanted to coach because all the coaches in my community were just the coolest dudes. They were well-respected, they had an air about themselves. That was something I wanted to emulate.”

There’s another keyword: Emulate. You can imagine Thorne whipping it out during their exercise on synonyms and antonyms: “What’s another word for ‘be like’?” “‘Copy?’ OK. ‘Imitate?’ I like that. How about ‘emulate’? That means when you try to be like somebody you admire, you emulate that person. Like, Langston wants to emulate me.”

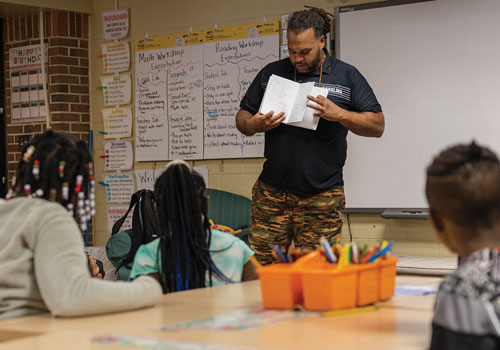

See, they don’t just talk at the kids. They move around, field questions and riff on each other’s words. Sometimes they even razz each other — whatever it takes to connect.

“We run a bait and switch, really,” says Thorne. “We come in as advertised, under the auspices of being a couple of former football players, and then we don’t talk about football for the rest of the presentation. We’re talking about reading and writing. Langston’s talking about real estate portfolios. I’m talking about being a teacher. The majority of our presentation is about everything else.”

Langston Moore breaks out his notebook of ideas so he can share it with students during a classroom visit at Seven Oaks Elementary.

Possibilities start here

The older the kids get, the more the presentations shift toward long-term goals. That means talking about success but also failure. Thorne’s college career ended with the knee injury. Moore played on Holtz’s beleaguered 1999 team — the one that lost every game — then played his entire NFL career without once enjoying a winning season.

Moore: “They all say, ‘I want to be famous’— well, what does that mean? The Detroit Lions were infamous for being 0-16. I tell them they’re looking at the world’s biggest football loser. I lost every game one season in college, and I lost every game one season in the NFL. But it’s about how you want to tell that story.”

It’s also about that all-important plan B, whether you need it right out of the huddle or further downfield.

Thorne: “One exercise we always do is we ask, ‘OK, who wants to be in the NBA? Who wants to be in the NFL?’ They all raise their hands, and we’re like, ‘Cool, you can do that. The only caveat is you don’t get to play.’”

And then the duo leads a high-energy brainstorm, rattling off careers that are more attainable and more sustainable. After encouraging kids to read, it might be the most important takeaway.

“We get them talking about all the other jobs they could do,” Thorne explains. “‘I could be a referee.’ ‘I could be a photographer.’ ‘I could be a beat writer.’ ‘I could be a video editor.’ If they really love sports, which is fine, they can still do something they’re passionate about in a way that makes sense for them.”

He pauses. He sees another keyword coming and smiles big. “Sometimes they don’t even know those careers exist,” he says. “It’s just a matter of making them aware of the possibilities.”