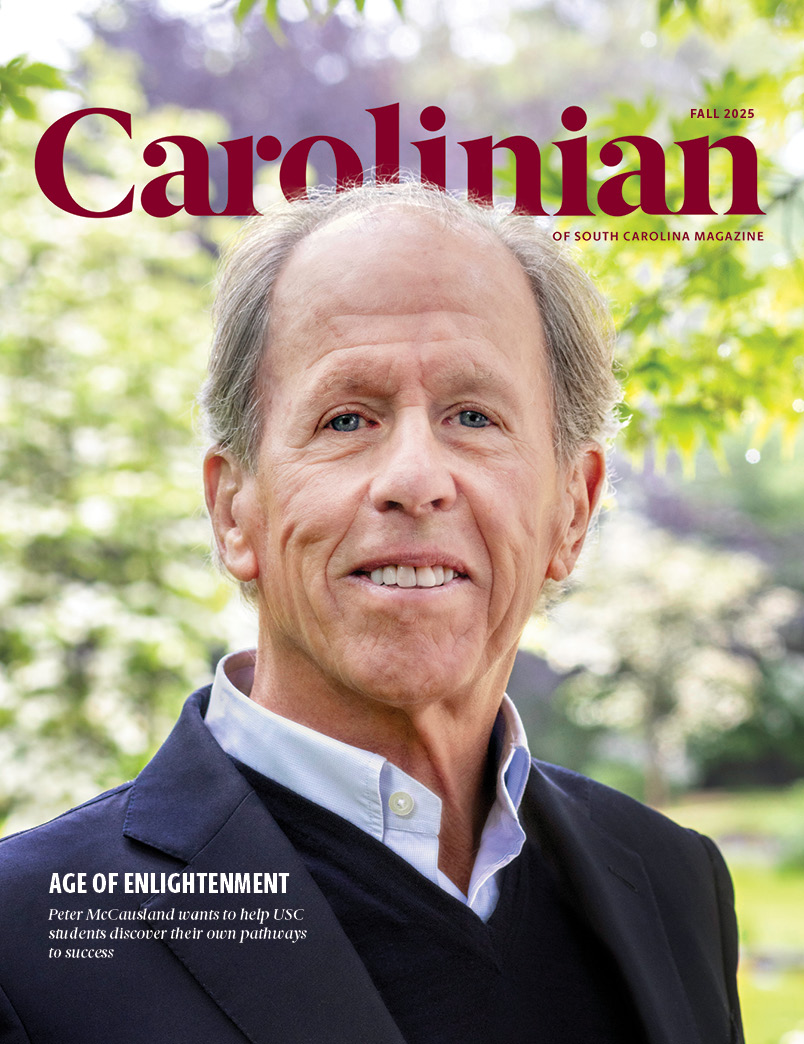

Photojournalist alumnus wins Pulitzer Prize

Win McNamee has spent 40 years documenting world history, national events

It’s a chilly, overcast day in D.C. as Win McNamee heads to the Capitol Building to do what he’s done for more than 30 years: photograph the people who carry out the nation’s political business.

In any other year, taking photos of Congressmen going through the perfunctory chore of certifying Electoral College votes would be an ordinary assignment.

But this is Jan. 6, 2021. “Ordinary” will never be part of anyone’s description of that day. As a riotous crowd smashes through police barriers and storms inside the Capitol, McNamee keeps his finger affixed to his Canon’s shutter button, capturing images that will shock millions across the nation and around the world.

Fourteen months later, in May 2022, McName's work and that of his fellow photographers at Getty Images was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in journalism.

Banner image: Supporters of former President Donald Trump storm into the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Getty/Win McNamee

‘This is a lot of fun!’

Win McNamee takes a break on a photography assignment.

It would be easy to say that Win McNamee was destined to be a professional photojournalist. He certainly has the pedigree. His father, Wally, worked for The Washington Post and Newsweek and covered 10 presidents, two wars and a raft of Olympic games enroute to receiving the National Press Photographers Association’s highest honor.

The question was whether Win McNamee had photojournalism in his blood. And the answer, at least when Win was a high school teen, would have been: apparently not. Wally gave his son a Nikon camera as a high school graduation present but following in his father’s footsteps was not what Win had in mind. He used the camera to snap pictures of his pals and applied to the University of South Carolina with vague plans of studying forestry or oceanography.

“I quickly realized there was far more science involved with those two professions than I’m comfortable with,” McNamee says. “At the same time, I started to work for the student newspaper, The Gamecock, because a friend of mine was there, and within a couple of weeks I was hooked.

“My very first assignment was sorority rush, which is not a bad assignment for a college freshman, and then there was a football game and a Greg Allman concert. I was like, ‘This is a lot of fun!’ ”

Not surprisingly, McNamee shifted his sights to journalism and was soon taking photojournalism classes with professors Don Wooley and Jack Hillwig, copy editing with Henry Price and a slew of other J-school courses. Those classroom experiences, he says, imparted “a very good foundational kind of journalistic training, both for the photographic aspects of the profession and the fundamental aspects of journalism itself.”

With scores of Gamecock photo assignments in his portfolio, McNamee earned his BA in journalism in 1985. Tom Priddy was photo editor for The State newspaper at the time, and as an adjunct instructor in the journalism school he had come across McNamee’s work.

“I thought, ‘Wow, we’ve got to get this guy working for us. He’s doing professional work already,’” says Priddy, who soon recruited McNamee to his staff of 10 newspaper photographers. “Win didn’t need any direction. He knew what needed to be done and went out and did it. You knew he would come back with something that was visually appealing, even if it was not a particularly appealing assignment.”

'Pivotal experience in my life'

Peach festivals, the Masters golf tournament, a KKK rally — whatever assignment, good or bad, McNamee always came back with a money shot. Priddy was aware that his young prodigy’s father, Wally, had made a name for himself in the world of big-time photojournalism but never detected any sense of entitlement in Win.

“Win had no pretensions,” Priddy says. “He was even a little shy about his skill. When I asked him to submit some photos for our monthly staff photography contest, it was kind of like ‘Aw shucks, can I compete against these other photographers?’ I was very sad when he came to me two years later and said he was leaving.”

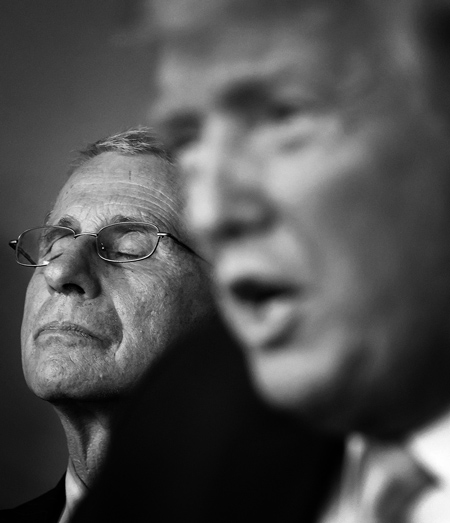

Dr. Anthony Fauci listens as then-President Donald Trump speaks during a news conference. Getty/Win McNamee

McNamee’s work at the newspaper had further honed his already considerable skills as a photographer, and, now in his mid 20s, McNamee wanted to see the world.

“When I left South Carolina, I freelanced for about three years and sort of had the travel bug. I had never traveled outside of the country before, and I was able to work stories in South Korea and Afghanistan, the Philippines and Cuba,” he says. “I was just hopping around covering whatever story I thought sounded good at the time.”

McNamee settled down a bit in 1990 when he became a staff photographer for Reuters news agency in D.C., a job he would hold for 14 years and that would further develop his professional chops as a photojournalist.

“That was like a whole other level of professional pressure and also learning what it means to be a reliable, reputable, ethical, information-driven journalist. It was a very pivotal experience in my life,” he says.

During those years, McNamee would cover the last half of George H.W. Bush’s administration, the Clinton years and the first half of George W. Bush’s presidency. “There were a lot of powerful stories during that period — the Gulf War, the bombing of the Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City, and, of course, the 9/11 terrorist attacks.”

As part of the White House press corps, McNamee flew on Air Force One with all of those presidents, often following them around the world. He was in the Florida elementary schoolroom on Sept. 11, 2001, when President Bush was interrupted while reading a book to children by a phone call that the Twin Towers were in flames.

He later accompanied the president to ground zero in Manhattan, capturing images of the devastation that shook the country and set in motion a cataclysmic response. “After having done it for so long, you kind of learn to set your personal feelings aside while you’re working and deal with the emotional aspect of it once you’re done covering the story,” he says. “Otherwise, you can’t do your job.”

'Personally, I abhor what took place that day'

In 2004, McNamee was offered a new position by Getty Images, becoming their chief news photographer in D.C., where he continued to shoot and oversee a large crew of staff photographers. Seventeen years later, he was with his team at the Capitol on the day the riot began.

“We expected a certain amount of trouble in the city because there were two rallies, one being hosted by former president Trump,” he says, “but we never thought for a moment that they would attack the U.S. Capitol, one of the primary symbols of our democracy.”

As the security perimeter was breached and public address announcements advised everyone inside to shelter in place and lock doors, McNamee knew it was no time for him to hunker down.

“For the next two hours the entire Capitol was just in chaos, a free for all in terms of people running helter-skelter throughout the building,” he says. “I’ve been doing this now for almost 40 years, and I’ve worked in D.C. covering Congress for close to 30, and I’m 100 percent confident that a lot of the things that I learned at the University of South Carolina School of Journalism and working for The State newspaper were just ingrained in my head.

“All of that cumulative experience in a situation like that allows you to work effectively and productively without getting distracted and overcome with the enormity of the situation you find yourself in.”

Situations like being face to face with Jacob Chansley, the self-proclaimed QAnon Shaman, who wore a horned fur hat and face paint while parading through the Capitol with a flag-adorned spear and was later sentenced to 41 months in prison for his central role in the riot. McNamee’s images of the bare-chested Chansley and other chaotic scenes in the Capitol that day were published and broadcast by news agencies around the world.

While many in that crowd were probably none too fond of mainstream news media, McNamee says he never felt personally threatened, a fact he attributes to trying to relate on a personal level to the individuals who were running amok through the building.

“Personally, I abhor what took place that day; that’s not the way we do things in this country,” he says. “But you try as a journalist to see or understand why people feel the way they do.”

Perry Baker, one of McNamee’s colleagues from his early days at The State newspaper, says an essential trait of solid photojournalism is being ready in the moment. “The ones that can understand what’s happening in the moment and be prepared to record that moment — it comes down to knowledge, preparation and anticipation,” Baker says. “I’m sure Win didn’t think twice about his own personal safety. He was in the middle of it, doing his job.”