Memories of a drowned town

Honors senior's thesis project explores history of a former SC mill town

Posted on: May 7, 2020; Updated on: May 7, 2020

By Carol J.G. Ward, ward8@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-7549

When 89-year-old Richard Mims was just a boy in the 1930s, he remembers playing a game he called “Executive” in the abandoned offices of the Santee River Cypress Lumber Co. in Ferguson near his hometown of Eutawville, South Carolina.

Mims’ father Franklin and several of his nephews were among the last employees who worked in the mill town, which existed from 1890 to 1940. The business itself operated there for a quarter century or so from the early 1890s to the late 1910s. Ferguson is now underwater at the bottom of Lake Marion.

When the lumber operations shut down, the company abandoned the offices and left all of their corporate records sitting in desk drawers at their headquarters, ripe for a young boy’s imagination. Mims’ father continued as manager of the property on which the mill was located.

“Before they built the dam to create Lake Marion, my father would go over to the site of the old Ferguson mill, where he had an office,” Mims says. “As a little boy starting about age 4 or 5, he took me with him during the summers - probably to get out of mother’s hair. Because there was nobody there but him, he liked the company. That’s how I had access to play with all the receipts and papers.”

Experiences become an oral history

South Carolina Honors College graduate Caldwell Loftis’ oral history shares the memories Richard Mims has of growing up near the drowned town of Ferguson, South Carolina. It will be transcribed and included with a collection of other items related to the town held at South Caroliniana Library.

Mims’ memories of growing up near the drowned town of Ferguson are the source for an oral history that South Carolina Honors College graduate Caldwell Loftis presented as his senior thesis in April. The two were connected by history professor Jessica Elfenbein who is working on a community study of the town of Ferguson from 1890 to 1940. The study covers the town’s creation out of the swamps, its existence as a mill town, its abandonment and finally its flooding by state-owned utility company Santee-Cooper to create Lake Marion. The mill and the town were built on a large swath of property, parts of which eventually would become Congaree National Park and Francis Beidler Forest near Harleyville, South Carolina.

“Mr. Mims is a very interesting man with a lot of stories to tell,” Loftis says. “I wanted to get a sense of what it was like living there and his personal experiences of growing up in the area.”

Mims and Loftis also share a connection through the University of South Carolina. Loftis is a 2020 graduate who majored in biochemistry and molecular biology in the College of Arts and Sciences and has been accepted to medical school. Mims graduated in 1959 with an education degree and worked for the university for 30-plus years, holding more than 20 positions ranging from bookstore assistant manager to assistant dean of the College of Applied Professional Sciences. He retired as professor emeritus in interdisciplinary studies in 1993.

Although the Ferguson mill closed before Mims was born, he remembers exploring the abandoned property with his father, an avid hunter and fisherman and assistant to the South Carolina agent for the mill’s Chicago owners.

“As far as we know, Mr. Mims is the last living person who personally experienced Ferguson, South Carolina, and he has this really fine memory of Ferguson as a little boy before it was flooded,” Elfenbein says.

The creation of Lake Marion

Mims was about 10 years old when the Santee River was dammed to create Lake Marion to supply hydroelectric power as part of the rural electrification efforts initiated under FDR’s New Deal.

“I remember they cut all of the trees and anchored them with heavy wire. They did not try to salvage it. There were thousands – perhaps millions – of board feet of cypress lumber they just left there which years later were recovered by underwater divers,” Mims says. "After many years under water, the anchor wires holding down huge trees rusted and broke. Many times one end of the tree was anchored and its top would be barely out of water or barely under water. Lake Marion became a hazard to boaters because of the submerged logs.”

Remnants of the abandoned town and mill were also left at the bottom of the lake; although, some parts of the mill remain above water.

Loftis’ oral history with Mims will be transcribed and included with a collection of other items related to Ferguson held at South Caroliniana Library. It preserves not only his memories of the drowned town but offers a glimpse into a bygone chapter in the state’s history, which Loftis says was a goal of his project.

“Mr. Mims has a unique perspective because he grew up during the Depression,” Loftis says. “It was interesting talking with him about what it was like in a small rural town in South Carolina then. As a young person, it’s important to speak to older people to learn what life was like and what has changed. Seeing the progress that can be made in someone's lifetime makes you feel like you can make impactful change in your lifetime as well.”

Ferguson’s place in SC history

In addition to his project with Mims, Loftis also worked with Elfenbein on research for her community study of Ferguson collecting, verifying and recording data about its residents from the 1910 census, the only federal census in which the town was included.

“In the bigger picture, Ferguson is really important because it tied rural South Carolina to Chicago and parts of this international commodity exchange for lumber,” Elfenbein says. “It was a big and sophisticated operation. Lumber was an important part of the U.S. economy during those years.

Ferguson was the headquarters for Santee River Cypress Lumber Co., which was started by Chicago lumbermen after the end of Reconstruction. Much of the lumber in the upper Midwest had been harvested, and land prices in South Carolina were cheap. They bought a huge swath of property in the middle of the state - close to 200,000 acres - along the Santee River. The two major principal owners of the lumber company were Benjamin Franklin Ferguson, thus the name of the town, and Francis Beidler.

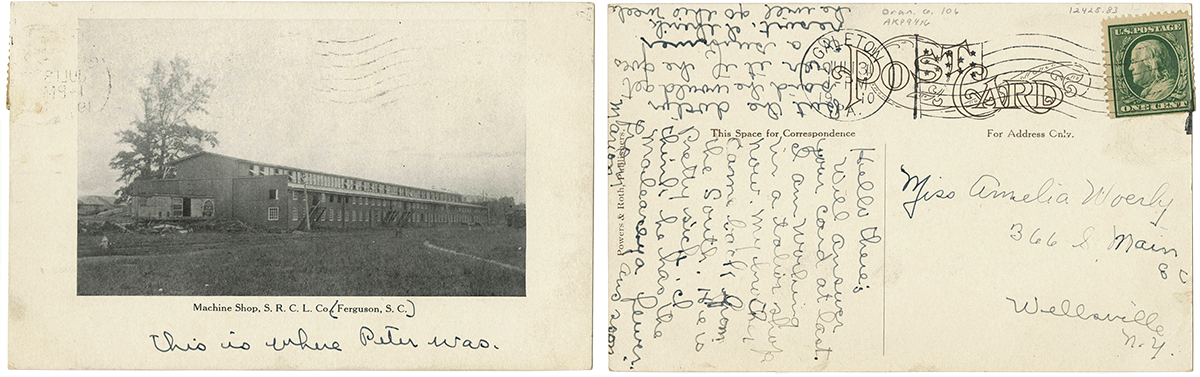

Santee River Cypress Lumber Co. was started by Chicago lumbermen after the end of Reconstruction. It was the South’s biggest cypress lumber operation. Photo courtesy of South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina

To attract workers from around the world, the company invested a lot of money to build Ferguson. It had worker and management housing, a hotel and a state-of-the-art school. It had its own hospital because of the risk of malaria in its swampy location, and like many company towns, it had its own scrip to pay employees. Company scrip was substituted for government-issued legal tender and could be exchanged only in company stores. The railroad also came to Ferguson to transport the cypress lumber.

“At its peak, it had a population of about 2,500, which for rural South Carolina in the 1890s and early 1900s is a good size,” Elfenbein says. It was the South’s biggest cypress lumber operation.

In addition to the lumber mill, the company also manufactured finished products such

as pickets for fences, cypress shingles and balustrades for hand railings. But by

1920, the company was out of business. The town was abandoned and then drowned by

Lake Marion, displacing 2,500 to 3,000 people, the majority African American tenant

farmers, in the surrounding communities. The property that wasn’t flooded remained

in the Beidler family and eventually became the core of Congaree National Park and

Francis Beidler Forest, a wildlife sanctuary of the National Audubon Society and The

Nature Conservancy.

Keeping history alive

“If you visit Lake Marion, there are no markers or anything that tells you Ferguson was there and was a state-of-the-art operation for its time or that thousands of people lived there or that there was a railroad or that 901 African American families were displaced,” Elfenbein says.

She says conversations are starting with South Carolina State Parks and other nearby stakeholders to explain the role Ferguson played from 1890-1940. One possibility is to create interpretive buoys on Lake Marion.

Research like Elfenbein’s and curiosity by students like Loftis also can help keep the town’s memory alive.

“The work that these students do is phenomenal and can be so important, and projects like this give a student like Caldwell a chance to go deeper,” Elfenbein says. “He's a major in STEM disciplines but chose to do his honors thesis in the humanities because he values being well-rounded.”

It also gives local residents like Mims a chance to share their experiences that shed light on the state’s history.

“I was surprised when Caldwell called me. I told him I didn't know why he wanted to talk to me because I don't think I'm that interesting,” Mims says. “Times have changed I guess, and I know about things more years back than a lot of people. I have memories about just growing up as a boy and about the town that’s not there anymore.”

Although he plans a career as a physician and focused his studies in the sciences, Loftis says history is one of his favorite subjects, and he was excited about doing his senior thesis in the humanities.

“I’ve been doing research on pharmaceuticals, so I could have done my thesis in my field because I enjoy that obviously,” he says. “But I've been doing science for four years and I'm going to do it for the rest of my life, so this was a good opportunity to diversify my learning experience and to appreciate history and the work that goes into figuring out the story and how it matters who tells the story.”