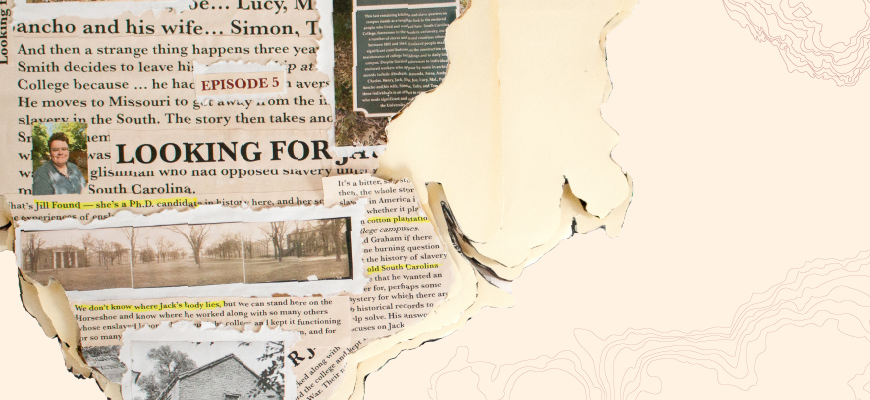

Looking for Jack

Remembering the Days: A UofSC Podcast – Episode 5

Posted on: March 31, 2020; Updated on: March 31, 2020

By Chris Horn, chorn@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-3687

The history of enslaved people at South Carolina College — the precursor of today's University of South Carolina — is a difficult one to tell. But research has brought to light the names of many of those individuals, and the university is acknowledging the vital role they played in the college's early days. Here's the story of one of those enslaved workers — a man named Jack.

Show notes

Learn more about the history of slavery at South Carolina, including maps and buildings of the antebellum campus.

Transcript

Looking for Jack

Abraham, Amanda, Anna, Anthony, Charles…

The names are common, but they have an extraordinary history…

Henry, Jack, Jim, Joe…

They’re the names of men and women who worked as enslaved laborers at South Carolina College, the precursor of today’s University of South Carolina.

Lucy, Mal., Peter, Sancho and his wife… Simon, Toby, and Tom.

I’m Chris Horn, your host for Remembering the Days, and today we’re looking back at a difficult chapter in campus history — the pre-Civil War era when slavery existed throughout the southern United States and left an indelible mark on nearly every aspect of society, including institutions of higher education such as South Carolina College.

I’m standing on the historic Horseshoe, where all but one of the buildings was constructed with enslaved labor and where many of the college’s daily activities, including cooking and cleaning, were carried out by enslaved workers.

Like several other institutions of higher learning across the country, the University of South Carolina has taken steps in recent years to formally acknowledge its historical ties to enslaved people. Those names at the beginning of today’s show appear on one of two markers here on the Horseshoe. They were installed in 2017 to provide a larger context for understanding the university’s antebellum past.

Duncan: Besides university archivist Elizabeth West I may be the only person who’s read all of the board of trustee minutes from the antebellum period. It was a thorough go through of all the antebellum records to see what I could find.

That’s Graham Duncan. He’s the head of collections at the South Caroliniana Library, and as an undergraduate history student here more than 15 years ago, he delved into the university archives to learn all he could about enslaved people at South Carolina College. He found official correspondence, receipts, and records of trustee and faculty meetings, which documented how the college rented enslaved workers from their owners and occasionally purchased its own slaves. Graham’s research paper marked the first foray into telling that story.

A few years after Graham’s paper came out, history professor Bob Wyeneth put his students to work on similar research that culminated with a website entitled Slavery at South Carolina College. You can find a link to the site in the show notes for this episode.

To help understand the context of what life was like for enslaved people on this campus, let’s focus on one particular person — an enslaved man named Jack who was purchased by South Carolina College in 1816.

Found: To me it’s fascinating and what clued me in that there’s something really important about Jack is about the lengths people go to to try and make sure that his labor is not lost by the university.

That’s Jill Found — she’s a Ph.D. candidate in history here, and her scholarly interest is in the experiences of enslaved people in urban environments. She has uncovered interesting facts about this slave named Jack, who served as an assistant to a chemistry professor named Edward Smith.

Found: Jack had been here very likely before Smith got here, working with the previous chemistry professor, but then it’s very clear from the records that Jack and Smith’s working relationship is a very important one to Smith. Smith relies extremely heavily on Jack’s intellectual and physical labor in the chemistry laboratory.

For several years, the college had been leasing Jack from his owner, a widow who needed the extra income. When she remarried, she didn’t want to rent Jack to the college anymore. That set into motion a whole chain of events. Smith pleads with the college’s Board of Trustees, telling them how vital Jack is to his work as a chemistry professor. The trustees get the governor of South Carolina involved, and he writes a letter to the state legislature, asking them to give the college money to purchase this enslaved man who apparently knew his way around a chemistry lab.

So Prof. Smith gets his wish and in the parlance of that day, Jack becomes the property of the college, guaranteeing that he will continue to assist Smith in the chemistry laboratory.

And then a strange thing happens three years later in 1819. Smith decides to leave his professorship at South Carolina College because … he had developed an aversion to slavery. He moves to Missouri to get away from the institution of slavery in the South.

The story then takes another twist. Smith’s chemistry professorship is given to Thomas Cooper who also was the second president of the college. Cooper was an Englishman who had opposed slavery until he moved to South Carolina.

Found: Cooper comes to South Carolina and ends up being a pretty ardent pro-slavery writer, thinker, really embraces the South Carolina way of life. He owns enslaved people on his own. His opinion on slavery changes.

Cooper has a completely different opinion of Jack. He calls him idle, careless, void of veracity and honesty. And in April 1821, Cooper asks the board of trustees for permission to physically punish Jack. Then, sometime between October 1821 and March 1822, Jack dies.

Found: We know that the university pays a doctor to treat him, but we don’t know what for or is it illness or physical violence that is responsible for him dying.

Jill doesn’t want to jump to conclusions about why Jack died. She points out that yellow fever killed a lot of people in South Carolina in the 19th century, and people died of all sorts of things in the days before modern medicine. Still, as a historian, Jill says it’s hard not to be suspicious of a connection between Thomas Cooper asking permission to punish Jack and Jack dying just a few months later.

It’s also troubling to note that students at South Carolina College were sometimes cited for physically abusing other enslaved people on campus.

Here’s Graham Duncan: There were some pretty shocking instances of violence, cutting an enslaved man’s face with a knife in the dining hall because he was insolent or something in his serving. A man was beaten at one point for informing on a card game that was going on in a dorm room, or a tenement room. A man had a what was described as a brick bat thrown at him, hit in the head, which I think is largely just a piece of brick, so there were some pretty horrific instances of violence enacted upon these people.

It might make you wonder what happened to these students. Were they suspended or expelled?

Duncan: They were brought in front of the faculty, admonished, and sent on their way with severe warnings or just gradual kind of step up in disciplinary actions and for the most part — and I don’t think this is a surprise necessarily — the students weren’t admonished or disciplined or called to task at all necessarily for the actual physical abuse of enslaved people.They were called to task because it wasn’t their place to do so. Because these were enslaved people either employed by the steward at the college or owned directly by the college itself. It was the steward or the faculty place to discipline, quote unquote discipline, enslaved people.

It's a bitter, sad story, but then, the whole story of slavery in America is tragic, whether it played out on cotton plantations or college campuses.

I asked Graham if there was one burning question about the history of slavery at the old South Carolina College that he wanted an answer for, perhaps some mystery for which there are no historical records to help solve. His answer focuses on Jack.

Duncan: We know he died (Jack) enslaved by the university. We know the university paid to have him interred. We know a man named Peter actually interred him. But we don’t know where it was. Probably in a potters’ field here in Columbia, but was it on campus? That’s the one real question I’d like to have answered, is “Where is Jack buried now?”

We don’t know where Jack’s body lies, but we can stand here on the Horseshoe and know where he worked along with so many others whose enslaved labor helped build the college and kept it functioning for so many years before the Civil War. Their names live on, and for that we are grateful.

It’s without question that our modern university is a beneficiary of the enslavement of African American people. This is but one of many steps that we must take as a university community to see more clearly who we once were in order to envision who we might be.

That’s all for this episode. We’ll be back with another story from the university’s past on Remembering the Days, a production of the Office of Communications and Public Affairs at the University of South Carolina.