The sounds of history

UofSC students help veterans tell their stories

Posted on: November 6, 2018; Updated on: November 6, 2018

By Megan Sexton, msexton@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-1421

Andrea L’Hommedieu understands what it takes to tell someone’s story — their full story, with the details and digressions, insights and epiphanies.

As the director of the oral history department in University Libraries, she records the memories and descriptions of daily lives, communities and events that shape the state and nation, and she makes those interviews available online for anyone to hear. She interviewed dozens of people to tell the story of Columbia’s Kline Iron and Steel Co., digitized interviews compiled for the 1977 International Women’s Year conference in Columbia, and sorted through shoeboxes full of cassette tapes that tell a family’s history.

This semester, she’s sharing her love of the story in an oral history course for Honors College students. Her 20 students are interviewing military veterans, learning the art of conducting one-on-one interviews, the skill of asking the right questions — and the discipline of staying quiet while the soldiers, sailors, airmen, marines and others talk about their lives.

“You can take written history and understand a piece of what happened. But if you can actually interview people who lived through it, you often get a dramatically different perspective,” says Tom McNally, dean of University Libraries. “A trained oral historian knows how to capture that.”

In library study rooms and in veterans’ homes, students have met and recorded conversations with veterans ranging in age from 34 to 95, covering every branch of the service and most major conflicts from World War II through Iraq and Afghanistan.

It’s a chance for history to come alive for students — and an opportunity for veterans to have their stories preserved through the university.

“What makes an oral history interview different from another kind of interview — a journalistic interview — is that we provide context,” L’Hommedieu says. “We talk about their military experience by first talking about their family, how they grew up. ‘What was that like?’ is a great question for an oral history interview. It’s open-ended. People can tell you how they felt about something to the degree they feel comfortable.”

Many of the veterans are from South Carolina, offering snapshots of growing up in communities and families around the state. Students are taught to ask questions that go backward before going forward, so veterans talk about parents and grandparents before describing their military service.

“You get some amazing stories when people recall their grandparents,” L’Hommedieu says. “Then you move forward: What brought you to the service? What influenced you in joining? Did you have other relatives that served in the armed forces? What were your biggest challenges? Were there particular events that were meaningful? And we added questions about friendships and mentors.”

For students such as sophomore Maddie Claire Porterfield, who interviewed Army veteran CeCe Mazyck for the oral history class, the project was a chance to hear about a remarkable life. After graduating from high school in Columbia, Mazyck went to school to be a fashion stylist. She soon figured out she wanted more education, so she joined the Army Reserves to earn money to pay for school. She loved the Army and its mission and eventually joined the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg. While she was making a routine jump in 2003, a strong gust of wind caused her to collide with a fellow jumper, and the two parachutes became tangled. Mazyck landed hard, fractured her back and became paralyzed. At the time, she was a single mom with a 1-year-old son.

Mazyck’s military story doesn’t end there. Now a graduate of the University of South Carolina, she’s an ambassador for Disabled American Veterans and competes around the world in the javelin and shot put from her wheelchair as a Paralympian.

“I want to motivate and let individuals know a life is not over when a disability occurs. Not only disabled veterans but those who are injured, blind, amputees, paralyzed like myself, to give them a sense of motivation,” she says. “I love telling my story to a student. When I’m out in society a lot of individuals stare and look at me. At first it was so hard for me. My self-motivation went down.

“I would rather they ask me a question or ask, ‘What happened to you?’ This experience is amazing because I get to share my story with a student who maybe can share my story with somebody else. So, if you see me or you see someone else, ask a question.”

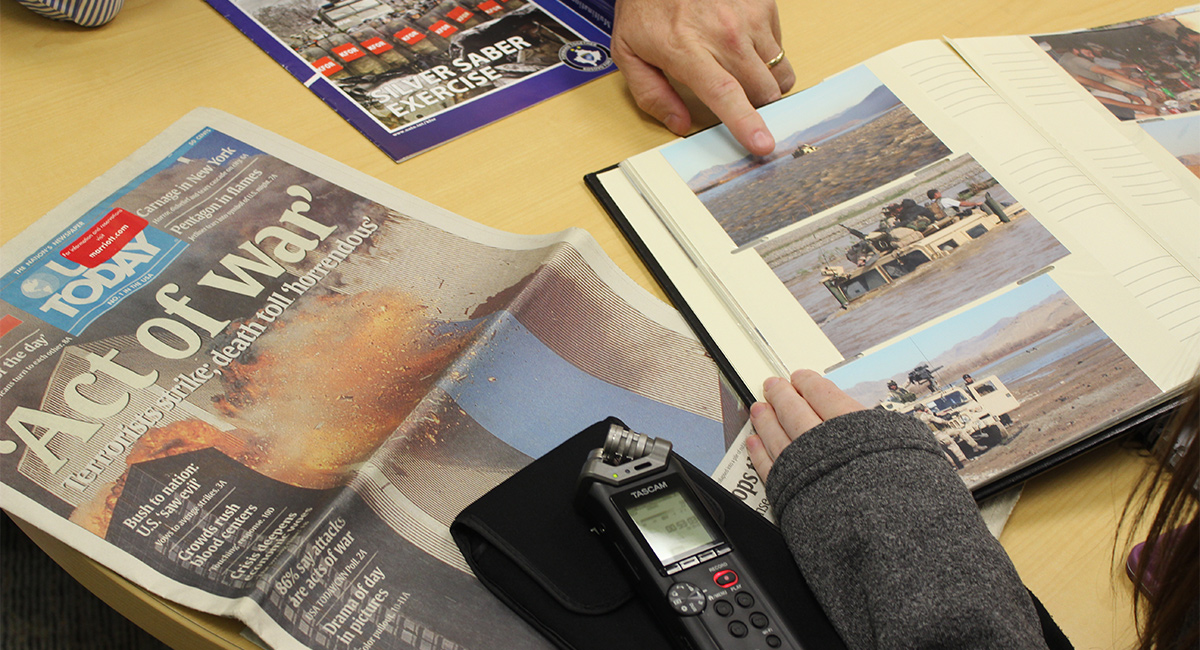

Senior Devon Cassidy interviewed Bryan Tolar of Columbia, who has spent 26 years in the Army National Guard, including four years on active duty for deployments in Afghanistan, Bosnia and Kosovo. Tolar brought along photos and maps from his time overseas, along with a copy of the USA Today newspaper detailing the events of Sept. 11, 2001, a paper he pulls out to read each year on the anniversary of the terrorist attacks.

Senior Devon Cassidy interviews Bryan Tolar of Columbia about his 26 years in the Army National Guard.

“I want to make sure we continue to catalogue some of these perspectives. There are so many I’ve met in the American Legion that have a unique story and no one has ever asked them. I’ve met a number of people who never wanted to talk, but they do now,” Tolar says.

He says it’s important to listen to veterans’ stories as a way to shed light on different cultures and offer people a new perspective.

“If we weave enough of these stories together you get a more accurate picture than one person going over and seeing what they see and saying this is the way it happened,” he says.

Cassidy said none of her family members have served in the military, so she was excited to get to learn about other people’s experiences. She said her other oral history interviewee, a Vietnam War veteran, told her how touched he was when people bought his meal in a restaurant or thanked him for his service when they saw him wearing his Vietnam vet hat.

“It made me really reflective, so that now when I see someone as a veteran it makes me want to go out of my way to say thank you or do something for them,” she says.

Once the students finish the interviews, the work continues to be sure the veterans’ words will live over time. Along with compiling a transcript, the interviews are recorded in Waveform Audio File Format (WAV), which can be migrated to new technology in the future. L’Hommedieu says it’s important that the interviews are used; that people know they exist. The interviews with the veterans will eventually be available on the library’s website, where they can be accessed by the public, while the students and veterans will meet at a December reception in the library to see the students’ final projects.

The library’s oral history department is still fairly young, she says, with more than 600 sound recordings online. This Honors College class will add at least 30 more. Those will include interviews from veterans such as Beth Karr, whose story was one of perseverance in a male-dominated environment. She served 20 years, starting in the Navy and transferring to the Coast Guard to teach Officer Candidate School when it opened to women in 1973.

Oral histories have been recorded routinely after World War II, offering first-person accounts of events and lives. Many have been done to understand social movements, including a collection of women’s history interviews in the 1970s when the Equal Rights Amendment was being debated. The university has 700 interviews in that collection, and has thus far digitized 300 of those and placed them on the website for the International Women’s Year collection.

“In the seven years I’ve been here, there’s been incredible growth. There’s a better understanding of what oral history can do to augment the historical record,” she says.

L’Hommedieu says she hopes students in the class learn both how to ask questions and how to appreciate the history around them.

“They are going to develop an understanding of another generation. I hope they get that sense of empathy also. And they’ll develop great listening skills and think about how you ask questions. And maybe they’ll even like history a little more.”

Nick Moheban, a sophomore from the Boston area, says he took the class because it fulfilled his Honors College history credit.

“I’m really glad I did. It’s probably the best history class I’ve taken in my life. It’s non-traditional. Generally in history you memorize stuff — this war, that war. In this class, you get to learn about how to interview someone and apply your knowledge.”

Moheban interviewed veteran Mike Tuck, who served in the Vietnam War and spent almost 21 years in the military, including a stint in the White House. Moheban says he is now looking forward to learning more about his own family history. He has asked permission to use the recording equipment over Thanksgiving to interview his grandfather.

“My grandfather came here from Iran with no knowledge of English and became a surgeon,” Moheban says. “He’s told me bits and pieces. I want to bring the (recording) equipment home and document his life. He’s had a wild ride.”

Vets then and now