Music theorists are primarily interested in the components of music – the chords, the rhythms, the melodies – and how these things come together to create the sounds we hear and how these sounds affect people.

– J. Daniel Jenkins, Professor of Music Theory

“Music theorists are primarily interested in the components of music – the chords, the rhythms, the melodies – and how these things come together to create the sounds we hear and how these sounds affect people,” says professor Danny Jenkins.

Jenkins says this theoretical education is essential to a better understanding of music in the academic context. But because it can be technical, he is an advocate and leader in public music theory. USC was first U.S. university to offer a public music theory course, he says, and remains one of the few institutions to offer it in the curriculum.

“There is a real need and hunger for this knowledge across the public. It’s important to share information in plain, accessible language, and I’m interested in where they can find that knowledge” he says.

Making the basics accessible also is the goal with music history faculty who seek ways to engage students not only in but beyond the classroom.

“History is living and what students learn in my classroom is not a fixed subject,” says professor Sarah Williams. “Just this year, a new Mozart piece and a new Chopin piece have been discovered, and that knowledge changes the way we think about history.”

To engage students in these foundational subjects, faculty often incorporate experiential learning opportunities, field trips, collaborations and independent projects.

Community collaborations

In spring 2023, students in Jenkins’s public music theory class worked with four mothers at Toby’s Place in Columbia, South Carolina, to write original lullabies for their young children. Toby’s Place is a shelter for unhoused single women or mothers.

The mothers knew what they wanted the lullabies to say and how they wanted them to sound, but they didn’t use the terminology that music students are used to.

“They're not saying words like crescendo and major and minor. They're talking the way they understand it,” Jenkins says. “For the students to be able to interpret that and turn it into music in the context of helping these women and their children during a transitional time is a wonderful example of the impact of community-engaged pedagogy.”

By that, he means working with a community partner to identify a need and then using musical knowledge and skills to help address it through collaborations such as The Lullaby Project, a national program created by Carnegie Hall.

In the spring, Jenkins’s class will be working with The Lourie Center for seniors on a project to explore the connection between music, memory and nostalgia.

The personal connection students make through community engagement projects brings deeper meaning to their learning, says Alyssa Santivanez (’23 master’s music performance with a concentration in community engagement).

“By working with the mothers in The Lullaby Project, I learned music’s power can provide hope no matter the bounds,” she says. “I used my passion for music as a platform to serve my community. Seeing how my music can encourage others to find their own creative voice provided a new level of inspiration for my musical studies.”

Community engagement efforts highlight a key mission of the university and the School of Music — to educate South Carolina’s citizens through community outreach to improve their quality of life.

Santivanez says this outreach helps students understand how music education can be used as a platform for social impact and positive change.

“The hands-on experience helped me learn how to use music to foster a supportive and successful environment, and that I can use my music to empower my community and spread hope,” she says.

Breaking down barriers

Music history professor and ethnomusicologist Alex Carrico uses her research to study how music can be used to break down stereotypes about disability. She became interested in these relationships after seeing a segment about Williams syndrome on a news program.

“Since I came to the university about four years ago, I cannot tell you how many students have approached me about doing research on music and disability,” Carrico says. “There absolutely is a need, and we are looking at ways to fill the gap.”

She incorporates discussions of disability in her music history classes, teaches a graduate course on music and disability and co-authored Disability and Accessibility in the Music Classroom, a guide for teachers to help make their classrooms more accessible to students with disabilities.

“Composers we study every day had disabilities, and it’s important to contextualize that for our students,” Carrico says. “Everyone knows Beethoven was deaf, but they might not know Bach and Handel went blind in their later years. They don't know about the mental health struggles of Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann.”

Carrico is in early collaborations with professors Mandi Schlegel and Wendy Valerio to explore how to better prepare graduates of the School of Music to work with students with disabilities. In February, Alice Hammel, an expert on teaching music to students with disabilities, will be doing a residency to work with students and offer a teacher workshop.

Students are involved also by doing surveys to identify gaps in music courses offered to students with disabilities in Richland County and designing a website to outline resources for teachers working with students who have visual or hearing impairments.

“One thing that is really special about our school is that our students are so engaged, and they want to want to make music accessible for everyone,” Carrico says. “My colleagues and I try to provide opportunities for students to explore their passions and to engage in public-facing research that can have a real impact.”

Experiencing history

Music history professor Williams challenges herself to make music history relevant and meaningful for her students. She provides experiential learning opportunities such as field trips and partners with local museums and libraries to engage students with the local community. Instead of writing a paper, she may ask them to use their research skills to write a fictitious podcast interview with a composer, a concert review or program notes for an Opera at USC production.

“I want to teach them the critical, listening, writing and research skills they can use not just in their music studies but in whatever they do,” Williams says.

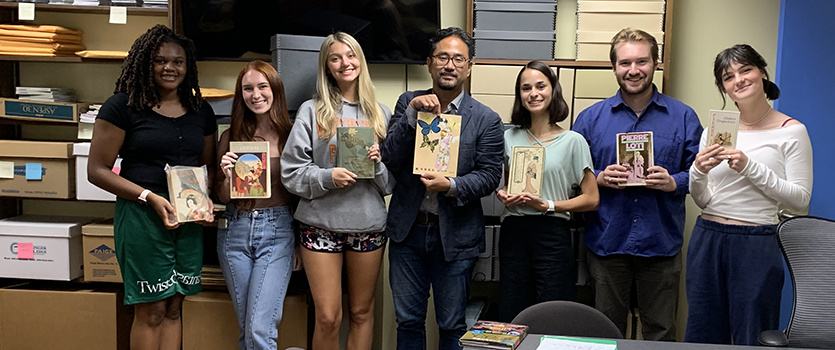

In 2023, Williams and her students built a digital humanities project, Singing the Archives, in collaboration with University Libraries and the Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. Undergraduate and graduate students chose medieval manuscripts, studied Gregorian chant notation, and worked together to organize the project.

Allison Yablonski, a Virginia native seeking a master’s degree in choral conducting, says students used skills they learned in class to transcribe, sing and record medieval chants. Being able to perform history was impactful, she says. Her chant came from a lampshade fashioned from medieval music manuscripts.

“Singing the Archives is one of the most engaging projects I've been a part of,” she says. “Interacting with this chant and remembering it could have been used in liturgical settings more than 600 years ago is inspiring.”

The project, funded by a Center for Integrative and Experiential Learning Unit Grant, culminated in professional recording sessions and an open-access digital exhibit. The goal is to add to the collection each semester.

“Students understand what they're doing is not just for a degree program or for their peers, but they here for the community,” Williams says. “Because we’re not in a major arts center, the university fills that role for the Midlands area.”

For Yablonski, it was special to give voice to an artifact and make it more accessible to anyone interested in music history.

“I hope our performances help inspire someone to learn more about where these chants came from,” she says. “Six hundred years ago, someone wrote on that very same folio that I was now performing from.”

Connecting music with culture

As a professor of ethnomusicology, Birgitta Johnson studies the intersection of music and culture, and her classes reflect an openness toward musical experiences. Topics range from the Cultural History of Hip-hop Music and a survey course on Beyonce’s Lemonade to Black Sacred Music, the roots of the blues and world music.

Through the Lemonade course, Johnson allows students to interface with history as well as contemporary topics by exploring how African American women use music as a community building and advocacy platform. Johnson also encourages students to make connections through current events, such as the recent passing of Nikki Giovanni.

“The Black Arts Movement, an explosion of arts, culture and community engagement in the 1970s is literally the backdrop of hip hop in America. And Nikki Giovanni is an icon of that movement,” Johnson says.

Using music as a bridge to connect people is one of the core themes of USC’s School of Music. Much of Johnson’s research is done through engaging with communities. A recent example is the “More Than Rhythm: A Black Music Series,” a collaboration she spearheaded with the Columbia Museum of Art to explore the contributions of African American music.

Through her joint appointment with African American Studies, Johnson stresses the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to bring diverse perspectives to students.

“Gen Z students are creative and engaged with their approach to learning,” she says. “They are able to connect their personal experiences with the course material to bring new insights to the classroom.”

Johnson also serves as Associate Dean of Inclusive Excellence, a role that is informed by her experiences with an increasingly diverse music program. She says initiatives are designed to address the needs of the School of Music and its students. For example, the Career Closet, which was formed in response to student feedback, provides free professional attire.

“High-quality clothing for performances is expensive, and the Career Closet gives students one less thing to worry about,” Johnson says. “We’re also able to provide a comfortable and inclusive environment for all students regardless of their background.”

The math-music correlation

As a professor of music theory and composition, Reginald Bain describes music theory as the lifeblood of every practicing musician. It provides a framework and common set of skills for learning how to create, analyze and interpret music. As the director of xMUSE, USC’s experimental computer music studio, Bain and his students use that framework to create new music using technology.

A former trumpet player with a doctorate and master’s in composition and a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and computer science, Bain combines his three passions at xMUSE and through interdisciplinary collaborations such as the Mutational Music Project.

In the project, biology majors and composition students used computer-generated music to represent spontaneous genetic mutations. Created by Bain and biology professor Jeff Dudycha and funded by the National Science Foundation, the research combines big data and sound in a process called sonification to help students better understand spontaneous mutation by “hearing” it happen.

The course has been offered four times with more than 50 students participating.

“It has been a fascinating experience,” Bain says. “The biology students and music students were teaching each other about their fields. It was amazingly beneficial for everyone.”

Bain not only explores the music-math connection by creating music with a computer, but also in classes where he teaches how music can be understood through the lens of geometry. Math, he says, has an imprint on everything from musical notation and scales to pitch and patterns and even the physics that dictate an instrument’s sound.

“Using a computer to create music is a way to dream and explore,” Bain says. “The computer extends your compositional resources. Instead of having only a string quartet or wind ensemble available to you, you have almost an infinite number of instruments.”

Bain’s most recent composition, Lift Up Your Eyes, premiered in November at the Southern Exposure New Music Series. The multimedia work featured electronic music, a performance by the USC Chamber Choir, and images from the James Webb Space Telescope.

Music and media

Music history and film and media studies professor Julie Hubbert says her mom, an avid movie fan, inspired her specialty in what she calls music for screen media – movies, TV, streaming and video games.

“When I started 25 years ago, it really wasn’t a field, but it has slowly emerged,” Hubbert says. “Now students seeking graduate degrees in musicology are really interested in understanding how much music is a part of their mediated world.”

In her time at the School of Music, the music history faculty has grown from two members to seven. Hubbert says that growth has benefitted students with expanded areas of emphasis and expertise, including her media specialty as well as popular music.

With dramatic changes in technology, production, labor and platforming, Hubbert focuses on industry aspects with her students to help them understand how music shapes the narrative.

“We want them to develop to ask questions about how the music is making them feel,” Hubbert says. “Do I feel a certain way about the character? Is it scaring me? Is the soundtrack pushing me to an emotional response?”

She says her next challenge is to offer a class that deals with the hot button issue of AI, music and ethics.

Hubbert also oversees Carolina Core classes for all university students and uses that opportunity to make sure they learn critical listening skills to become good audience members. To engage non-music majors, topics such as the history of rock and intros to film or video game music have been added to the standard music appreciation topics.

“Our goal on campus is to make everybody aware of how important music is and to provide our students and community with skills to love, appreciate and consume music.”

100 Years of Music at Carolina

To commemorate its centennial year, the School of Music is showcasing its programs, alumni, students and faculty in a special series of stories and performances throughout the year. To read more about the yearlong celebration, click here. The theme for the historic milestone, “Sing Thy High Praise: 100 Years of Music at Carolina,” is pulled from the first line of USC’s alma mater.