The opioid epidemic has been on the rise in South Carolina for more than a decade. In both Richland and Lexington Counties, more than 100 people died from opioid overdoses in 2022. Statewide, more than 2,200 people died from unintentional overdose that same year.

Now, two University of South Carolina graduate students have recruited a new group of professionals to help offset the epidemic: Columbia’s local bartenders.

“We often hear this joke on sitcoms: ‘I don't see a therapist; I have a bartender,’” says Sarah Grace Frary, a doctoral student in USC’s clinical community psychology program.

“While it’s ideal for people to have access to trained professionals, our mental health systems are overstretched. So, I thought it could be helpful to equip communities with the resources that they need to meet the opioid crisis where it's at.”

Together with Jessica Pomerantz, another doctoral student in the program, Frary is studying how community members such as bartenders can intervene when they see opioid misuse happen at their venues.

“These are people who have closer proximity to substance use and are often very trusted members of their community. There is potential for them to communicate with others about concerns related to substance misuse,” Frary says.

With grants from the American Psychological Association, Frary and Pomerantz have led focus groups to learn about the experiences of bartenders, musicians and others in the entertainment and hospitality industries.

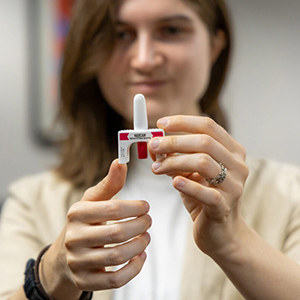

After each focus group, they train participants on how to use Narcan, an emergency medication for opioid overdose. They also teach them about fentanyl test strips, which can alert an individual if fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, has been mixed into a substance.

By gathering data from these conversations, they hope to identify ways that establishments can offer support and resources for their staff.

Equipped to fight opioid misuse by USC fellowship

Frary and Pomerantz were both fellows of USC’s Integrated Care for Recovery center, or the I-CaRe center, which is directed by Sayward Harrison, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology.

The one-year fellowship trains future psychologists in the prevention and treatment of substance use disorder and places students in externships with community partners. Frary says the fellowship also helped her reconnect with community-based research, which was one of the main reasons she chose USC for graduate school.

She was in the first cohort of the program, which launched in 2022 with a federal grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration. By 2025, the program will have trained 18 fellows to help bridge the gap in professionals to help combat the opioid epidemic in the state and the nation.

Jessica Pomerantz joined the fellowship in its second year. She says the training will help her reach her goal of becoming a therapist working specifically with people employed in the food and beverage industries.

For Pomerantz, the focus groups are especially personal because she is a part of the local bartending community.

“I've been bartending since I was old enough to obtain a job, basically. It's been my family,” she says. “Hospitality has always been something very near and dear to my heart.

Pomerantz worked at some of the top bars in New York City and placed first in a national competition for women bartenders. When she moved to South Carolina to go to USC, she continued bartending and helped local restaurants develop their cocktail menus.

As an insider in the local hospitality industry, Pomerantz helped Frary get community buy-in for the project.

“One of the biggest challenges with harm reduction efforts in the hospitality community so far has been getting people to keep Narcan on site,” she says. “It’s kind of like, if you keep it, you're admitting you have a problem in your space.”

But Pomerantz says the problem of substance misuse hits close to home for many who work in the industry. She has also seen firsthand the deadly effects of opioid overdose in her own community.

“It would be hard for you to find a hospitality industry person who doesn't know someone who's overdosed. It's been a huge issue and it's getting to be more common than I think anyone's comfortable with,” she says.

The measure of success in fighting the opioid epidemic

Experts say that distributing Narcan widely has likely helped curb deaths from opioids in the last year. In fact, preliminary data from the Center for Disease Control predicts that 2023 saw the nation’s first drop in overdose deaths since 2018, with a decline of more than 6 percent in South Carolina that year. 2024 is looking even better for the state, with an predicted decline of 7 percent.

Harrison says she is proud the I-CaRe center is part of that progress, and she hopes to continue the work with a renewal of their grant funding in coming years.

“Since launching the fellowship, we’ve integrated our psychology trainees into many different settings, ranging from outpatient clinics at Prisma Health to The Courage Center, a recovery community organization, to a new school-based prevention program and online training modules for school nurses and other professionals,” Harrison says.

“We have to tackle this problem from multiple angles, and the fellows have brought so much innovation to their work in the community and the state, including policy-based research and novel community interventions.”

While the data may indicate that the work is making an impact on the state, Pomerantz says she uses a different number to measure success: zero.

“I’m thankful that I haven't had any friends die of an overdose in the last year,” she says. “That's what we call a win in our community. That's how I think about it, but it breaks my heart to say it out loud.”

Additional Resources

- South Carolina residents can find more information about how to access Narcan and fentanyl test strips from the South Carolina Department of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services (DAODAS).

- For USC students, Gamecock Recovery is an excellent resource for connecting to an array of tools and services to reduce harms associated with substance use.

- USC is a designated a community distributor of naloxone through DAODAS. You can get a supply of Narcan for free at the SAPE Office, Suite 301B in the Wellness & Fitness Center, during weekday business hours.

- Learn how to get a supply of Narcan and training on when and how to use it.

Banner image: Jessica Pomerantz at Smoked in Columbia, SC. Photo credit: Lynn Luc @curatedwithlynn.